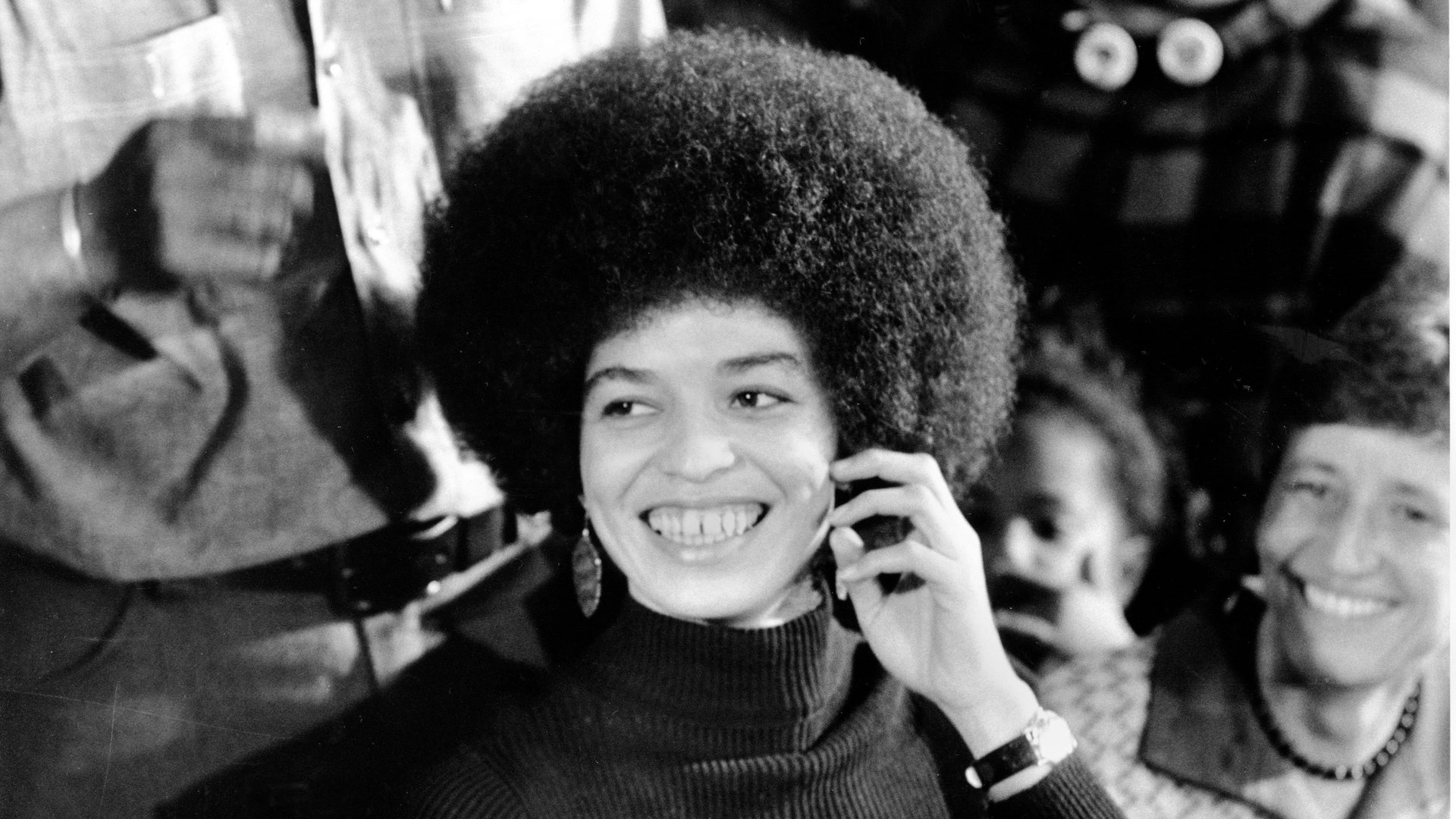

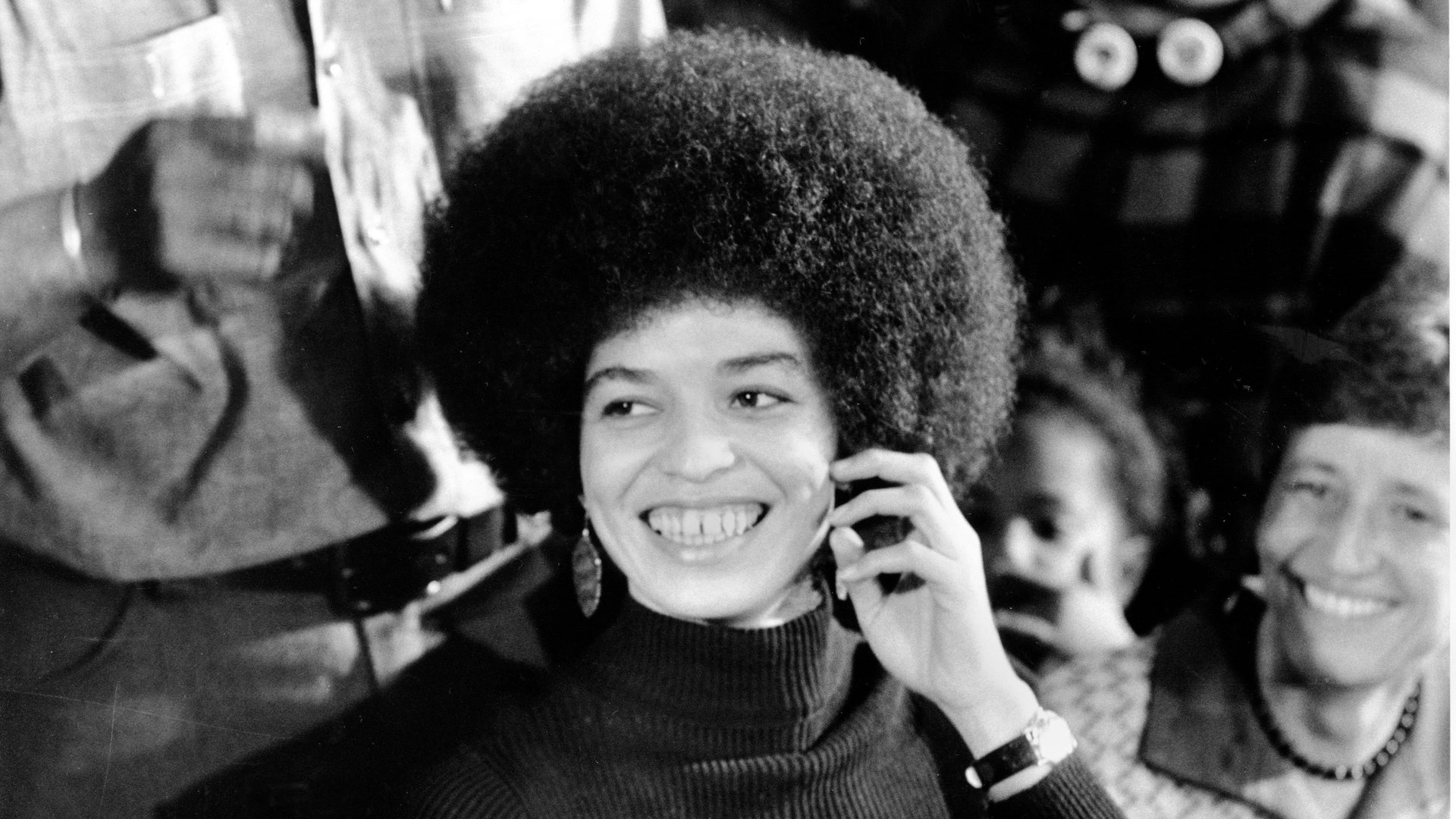

It took a 13-year-old girl with an Afro to make South Africans notice their racist school dress codes

A hairstyle should not have to be a radical political choice, especially for a girl only just beginning to navigate high school. But this week, a 13-year-old girl’s determination to wear her Afro revealed how race still informed school policies and social perceptions of what is acceptable behavior for black South Africans.

A hairstyle should not have to be a radical political choice, especially for a girl only just beginning to navigate high school. But this week, a 13-year-old girl’s determination to wear her Afro revealed how race still informed school policies and social perceptions of what is acceptable behavior for black South Africans.

Students in school blazers and tunics protested outside the Pretoria High School for Girls, demanding the school change its policy that effectively banned Afros and unfairly policed its black students. After an emotional meeting with the school’s governing body, teachers, parents and affected students, the provincial education authority suspended the school’s hair restrictions and ordered an investigation.

Rigid school policies are common in South Africa. The young teenager who has become the face of this growing movement has had to change schools three times because of her hair. Her older sister wrote about how proud she is of the 13-year-old. She also feared the emotional toll of the rejection that drove her little sister to protest.

That rejection felt by young black children is not uncommon in institutions that were exclusively white just over twenty years ago. As apartheid ended, black children who could afford it (or on a bursary) were bused into white schools for the first time, finally able to access the resources and networks of the country’s elite schools.

The demographic of these schools may have changed, but their policies did not. Many of these schools are about a century old, steeped in history and tradition and seemingly oblivious to how those rules excluded black South Africans. Authority figures remained white and often insensitive rules around language and appearance were enforced in the name of tradition. White people make up 8% of South Africa’s population, while black people are 80% of the population.

At first, black students assimilated. However, as recent university mass movements like #FeesMustFall and #RhodesMustFall showed, this is a more assertive generation forcing establishments to evolve rather quietly fitting in. They also have the support of parents and alumni who understand the emotional damage caused by suppressing African identity and culture in a country where white South Africans still enjoy a privileged place.

Within a day after the public complaints at Pretoria High School for Girls, another prestigious girls’ school, Johannesburg’s Parktown High School for Girls, amended its hair policy as a “proactive” move to avoid “subtle or structural racism.” The move was to ensure the schools pupils felt “comfortable with what they consider to be their natural hair,” the school said in a Facebook post.

Another elite school, St. Michael’s in Bloemfontein, could not avoid scandal after an irate parent posted photos of black girls lined up to test their neatness. The girls’ hair had to fit into a swimming cap or school hat as a test of their compliance with the uniform code. While no white girls were seen undergoing the test, the school defended their policy.

“This is not a white or black issue,” said the school governing body chairperson Brian Sweetlove. “This is about the amount of hair that can fit into a swimming cap.” After public outcry, the school has promised to reconsider their policy.

But policies don’t change perceptions. South Africa’s corporate spaces may not be governed by rigid constitutions, but they still reflect the rules of these elite schools. In the workplace, few of the women celebrated for excellence in their fields sport their natural hair. Those who do, ensure that their hair is scraped back or cajoled into an inoffensive hairstyle. Large puffy Afros, intricately patterned cornrows or long thick dreadlocks are not to be taken seriously, is what the message reads.

What is considered neat and professional is still influenced by social views that exclude people of African descent’s natural appearance. And it’s not just in South Africa. Earlier this year, a Google Image search of “unprofessional hairstyles for work” yielded pictures of black women with natural hair. And there are real world examples of women who say they lost their jobs for wearing their natural hair.

It’s why black women’s decision to cut off their chemically straightened hair is a radical one. Women wearing their natural hair have sought camaraderie through social media, spawning a global movement that has created new business and undermined the monopoly of chemical hair straighteners in the hair industry.

It’s an affirmation of an identity that is only just beginning to claim a positive space in society’s imagination. The way African hair springs out of follicles, defying gravity, politics and stereotypes, is beautiful. It’s taken decades for black women and men to embrace it, but it seems it’s taking the rest of the world a little longer.