Civil rights icon Angela Davis wants young activists to challenge their heroes

Pretoria, South Africa

Pretoria, South Africa

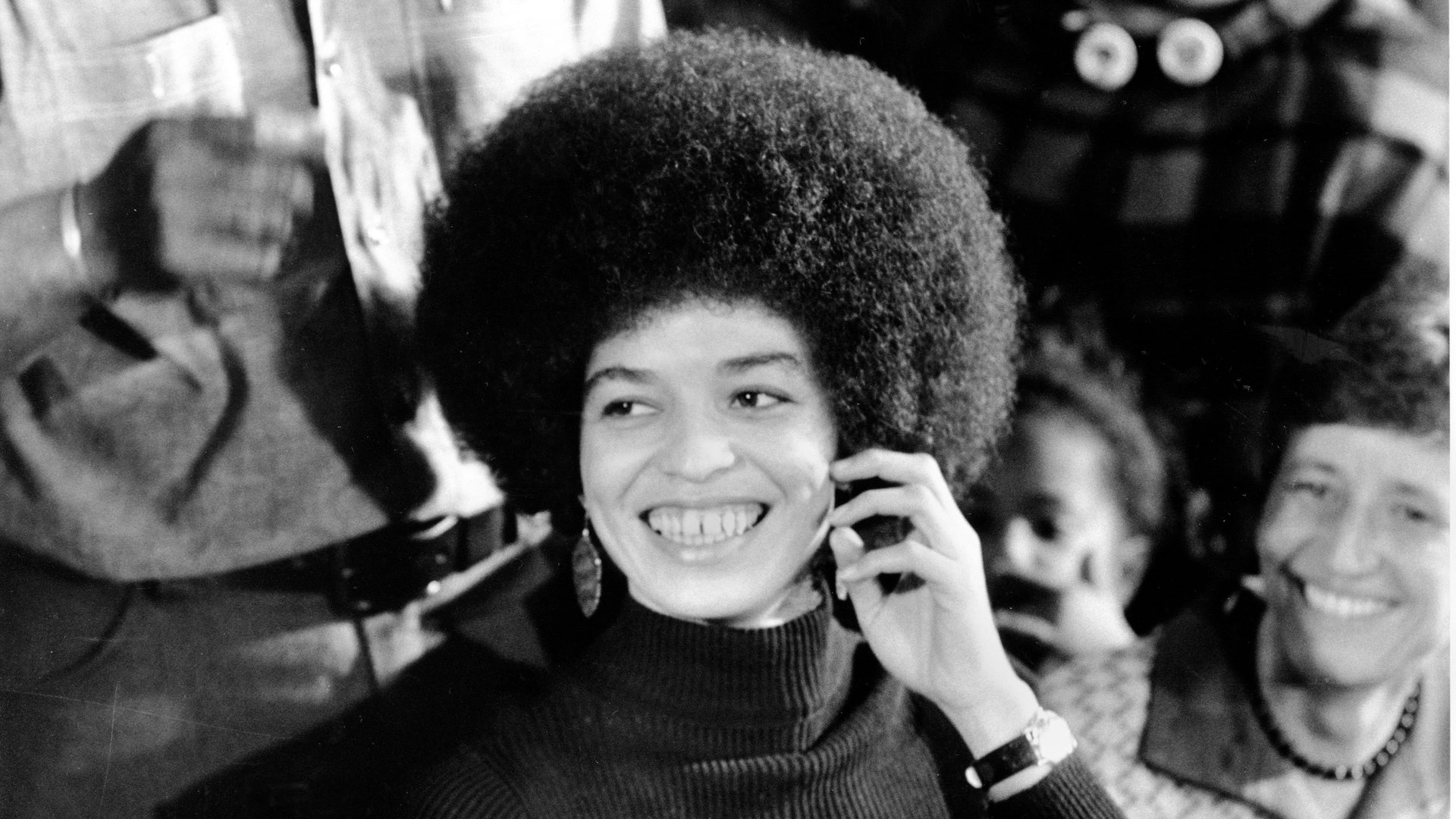

Just a peek of Angela Davis’ iconic Afro making its way up the stairs and onto the stage was enough to send the crowd at University of South Africa (UNISA) into a frenzied applause. Davis was clearly overwhelmed.

She would be interrupted several more times as the packed Z.K. Matthews Hall stood to applaud throughout her address as keynote speaker at the 17th annual Steve Biko memorial lecture on Sept. 9. She was even welcomed by a traditional praise singer. For those who could not find a seat, Davis’ lecture was broadcast live on two national news channels and several radio stations.

The civil rights activist and academic came to South Africa as a guest of the foundation created to honor Biko, the slain activist known for bringing the black consciousness movement to South Africa during apartheid.

Both Davis and Biko are icons of black intellectualism, who found their respective voices as young activists in anti-racism movements in South Africa and the United States. Davis’ political activism began with the Black Panther movement, during which her imprisonment launched a global solidarity movement. Today, she is a professor whose work focuses on feminism and black consciousness and her activism has extended to mass incarceration.

Davis speaks to a South Africa where the legacy of segregation is still felt. Days before Davis’ arrival, students at the University of KwaZulu-Natal torched a library out of frustration over stalled negotiations on free education. Last month, a group of schoolgirls protested for their rights to speak African languages and wear Afros as large and defiant as Davis’ still is. Throughout her activism, South Africa loomed large as a beacon of hope, she told the crowd.

“I would not have been able to imagine then, that two decades after the defeat of apartheid we would be confronted with militaristic responses to people’s activism,” said Davis. The schoolgirls were in the audience, and Davis had met with the university student leaders of the #FeesMustFall movement before her lecture. In support of a no-fee school system, Davis stressed that freedom of education should equate to the ability to pay for that freedom. Again, the hall erupted.

“As dissatisfied as we are with the present, this is the present that was ushered into being by past revolutionary struggles,” said Davis. “The revolution we wanted was not the revolution we helped to produce.”

“So when I reflect on the current moment, when I reflect on the United States, I ask myself what might we have done differently had we known that the election of the first black president would be followed by the farcical election campaign we are currently experiencing,” she said, refusing to say Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump’s name more than was necessary—just once.

Davis, examining the decades since she found a voice as a young activist, questioned whether she and her compatriots should have fought not only for structural change, but challenged the emotional and cultural effects of racism on all people. As a new generation of activists begin to find their voices, Davis urged them not only question the celebrated legacies of leaders like Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King, Biko’s and even her own, but to devise a new language of struggle. Young activists have the capacity to ask questions that her generation did not, and they should be allowed to do so, said Davis.

But there is an uneasy relationship between the generations, she admits, and perhaps that was because struggle veterans took themselves too seriously. Davis drew parallels between the young activists in South Africa and those of the #BlackLivesMatter movement—both led by young women, both built on the legacies of activism, yet challenging those legacies by creating movements that are more intersectional and democratic. These are movements that made room for women, the LGBTQI community, the environment and collaboration with international movements, especially through social media. And when those movements falter, they should be supported and allowed to grow and become part of a long civil rights history.

Davis seems to have accepted that she may not see the complete fruition of the ideals she fought for so long and so hard. No longer the young firebrand but the more reflective and still impassioned academic, Davis sees the struggle for equality and justice as one that is a historical continuum and one that will extend from black people to all of humanity. Her faith in a new generation of activists is evident by her refusal to prescribe to young people, but to listen and collaborate.

“Even though there are never guarantees that we will reach the futures we dream, we cannot stop dreaming and we cannot stop struggling,” she said. “There will always be vibrant legacies, there will always be unfulfilled promises, there will always be unfinished activisms.”

Davis ended to another lengthy standing ovation. And when Davis accepted a gift of pencil-drawn portrait from the organizers, it was the schoolgirls of Pretoria High School for Girls, who came down from their seats to present it to her.