Photos: For Senegal’s jailed minors and street kids, fencing is more than just a sport

The West African nation of Senegal has a child problem: tens of thousands of street children, aged between 5 and 15, victims of forced begging and abuse, roam its streets.

The West African nation of Senegal has a child problem: tens of thousands of street children, aged between 5 and 15, victims of forced begging and abuse, roam its streets.

Some of these children are known as the talibés: they are sent hundreds of miles away from home by their parents to receive religious education. Some of them also come from neighboring countries such as Guinea, Mali and Guinea Bissau. However, some of the religious instructors, also known as marabouts, exploit the children, forcing them into begging, and in some cases, beating them to death.

Parallel to the talibé problem is the number of incarcerated minors in the country. Almost 5% of the country’s prison population is under the age of 18, according to one estimate cited by the Open Society Initiative for West Africa (OSIWA). Many of these children also face dire conditions in prison, including lack of basic food and sanitation needs, proper education, or getting prepared for social reintegration.

In response to this problem, OSIWA started a fencing practice with a local organization called Association pour le sourire d’un enfant (ASE) for incarcerated minors and street kids in 2012. The project was started in the prison in Thiès city, an important economic and transport hub and the gateway to the capital, Dakar.

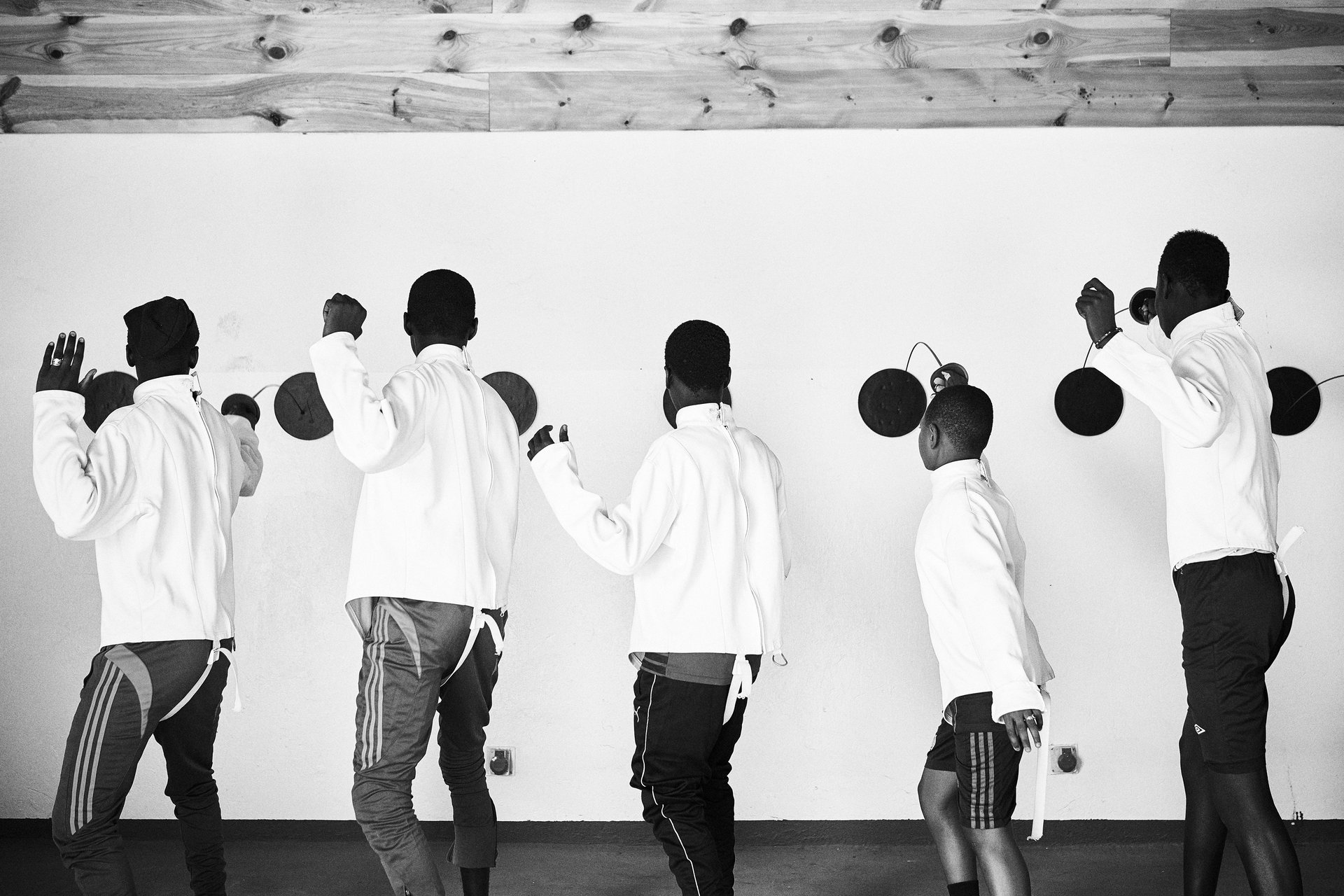

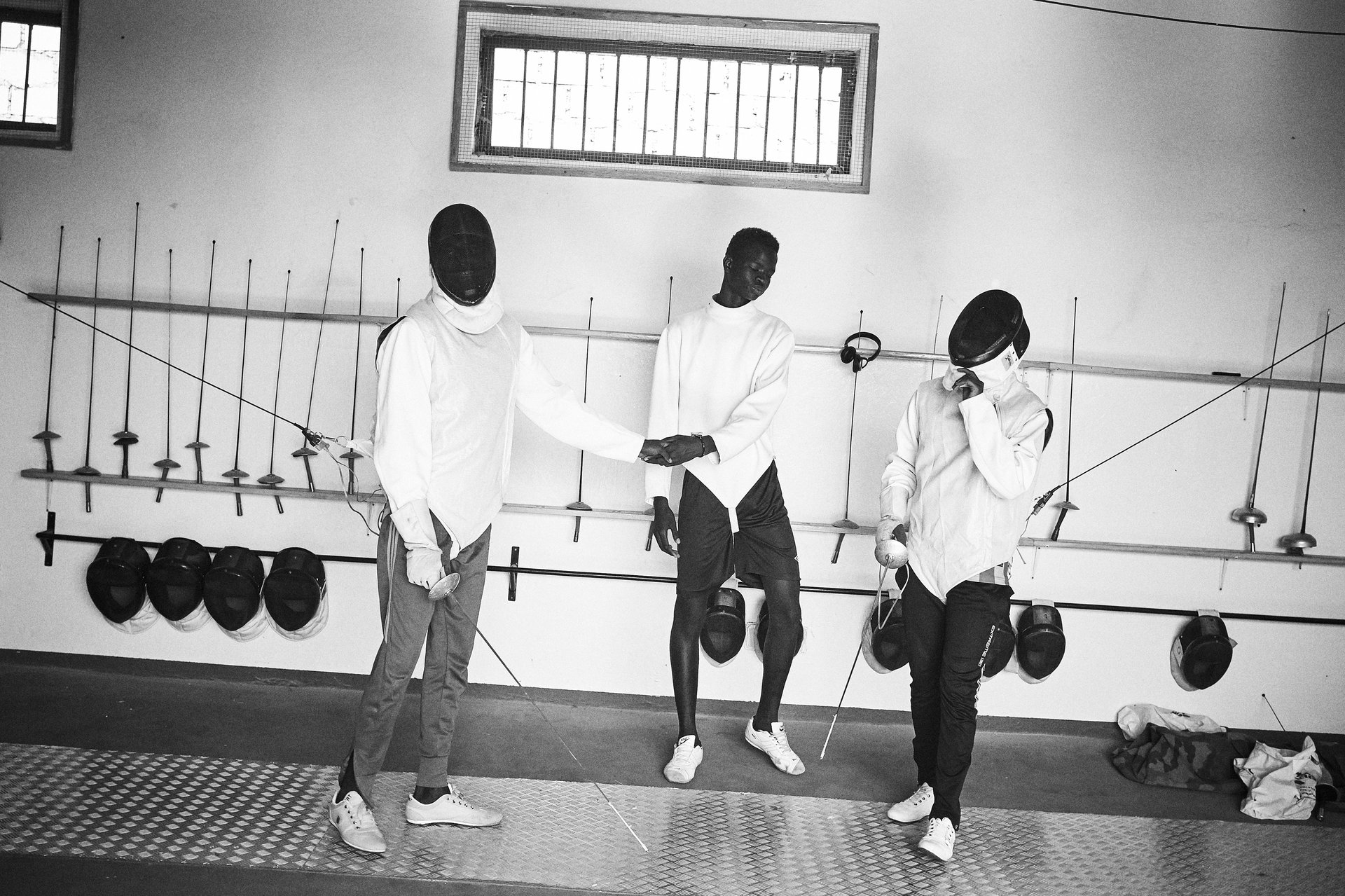

The fencing project was launched as a way to encourage social harmony and dialogue between juveniles and law practitioners. Photographer Sam Phelps captured the boys and girls as they were being instructed on fencing techniques.

“Prisoners often face particular difficulties from a societal perspective, both during and post-incarceration,” says Hawa Ba, who manages the fencing project. “This can be especially damaging for youth, who have their whole lives in front of them and may not ever recover from the heavy social stigma that falls on them once having served time behind bars.”

The project uses the sport as a form of restorative justice, giving the minors an opportunity to help them deal with their troubled pasts. The street children are given the chance to attend once a week, while the incarcerated youth attend the training twice a week.

The sessions also give the detainees the chance to take part in activities outside the prison’s compound. Fallou, an inmate at the prison, said that it was previously hard “to stay every day in the same place, and to watch always the same people.” With the fencing, he said, “If we go out to the center or the fencing studio, we are so happy to see the street.”

The training is also done as a way to reduce violence in the prison environment, and to offer a space for socialization, discipline, and self-control. The intention, prison guard Fatoumata Sy says, is to show them that there are rules and laws in all aspects of life and that they have to adhere to them while living amongst their communities.

Young detainees also receive the opportunity to speak with educators about their fears and prospects for the future. Many have also spoken about their tales of arrest, the procedural delays, and their sentencing.

For prison officers, the fencing project creates the chance to have a relationship based on dialogue and trust. The Senegalese Federation of Fencing, in collaboration with the French Federation, have further designed a training aimed at offering guards and educators the possibility of becoming certified fencing instructors.

More importantly, the sessions offer young detainees the opportunity to speak with these educators about their fears, regrets, and dreams for the future. Many have also spoken about their tales of arrest, the procedural delays in their cases, besides their sentencing. OSIWA says this communication relieves the stress that inevitably accumulates between the children, the police and the prosecutors throughout the course of the hearings.

“The prison workers have been able to gain the trust of the minors, creating a space that allows them to open up and tell them their personal stories,” Ba, the program manager, said. “It also teaches the youth about honesty and can play a huge role in calming kids and teaching them how to accept defeat.”

Instead of looking at the children’s time in prison as punitive, fencing brings a rehabilitative approach to their incarceration, says OSIWA. It’s one step forward in ensuring that they reintegrate better and are able to forge healthier social ties once released.