Donald Trump may push African countries away from America and closer to China

A Donald Trump presidency might push Africa in the direction of China.

A Donald Trump presidency might push Africa in the direction of China.

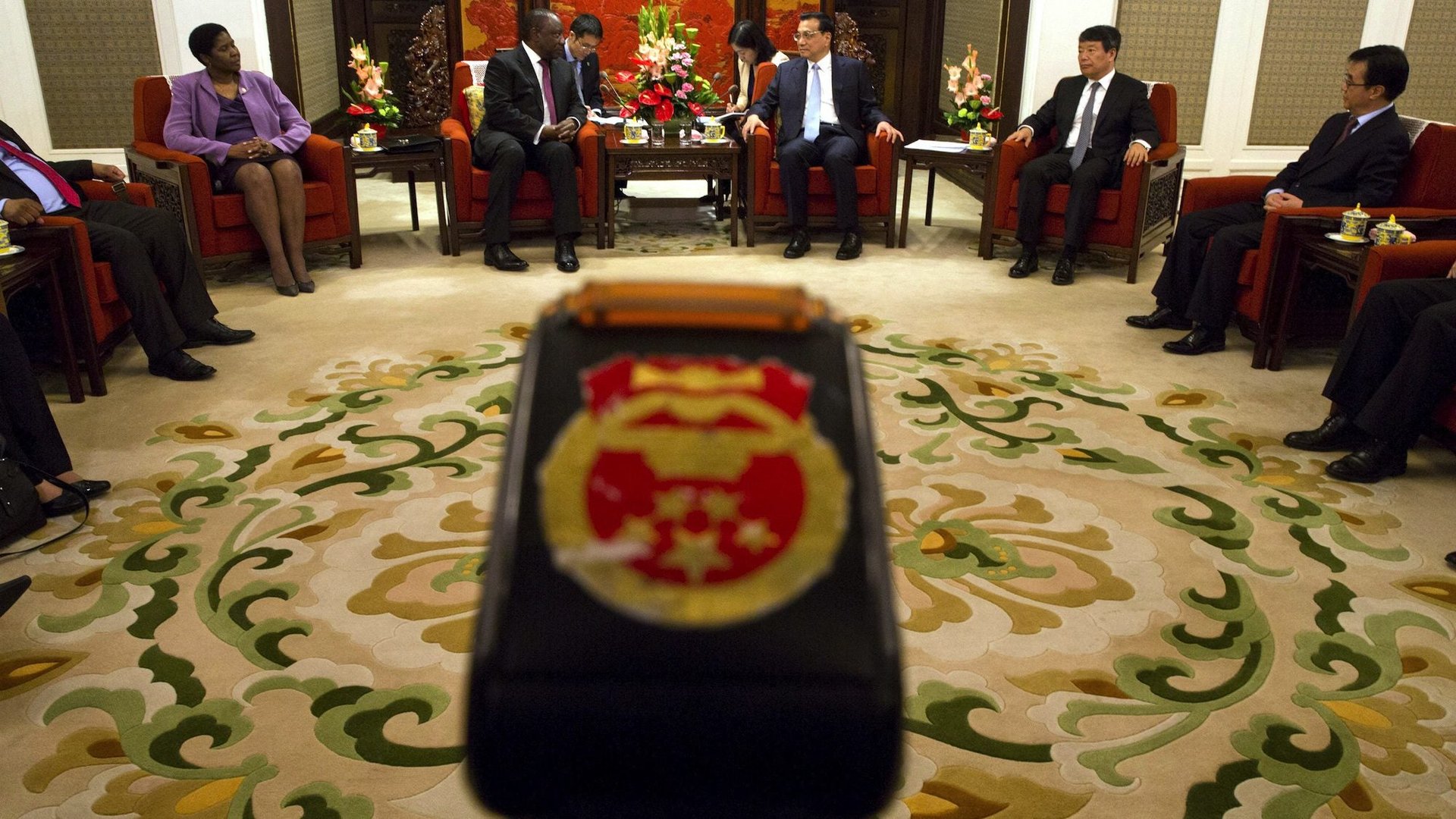

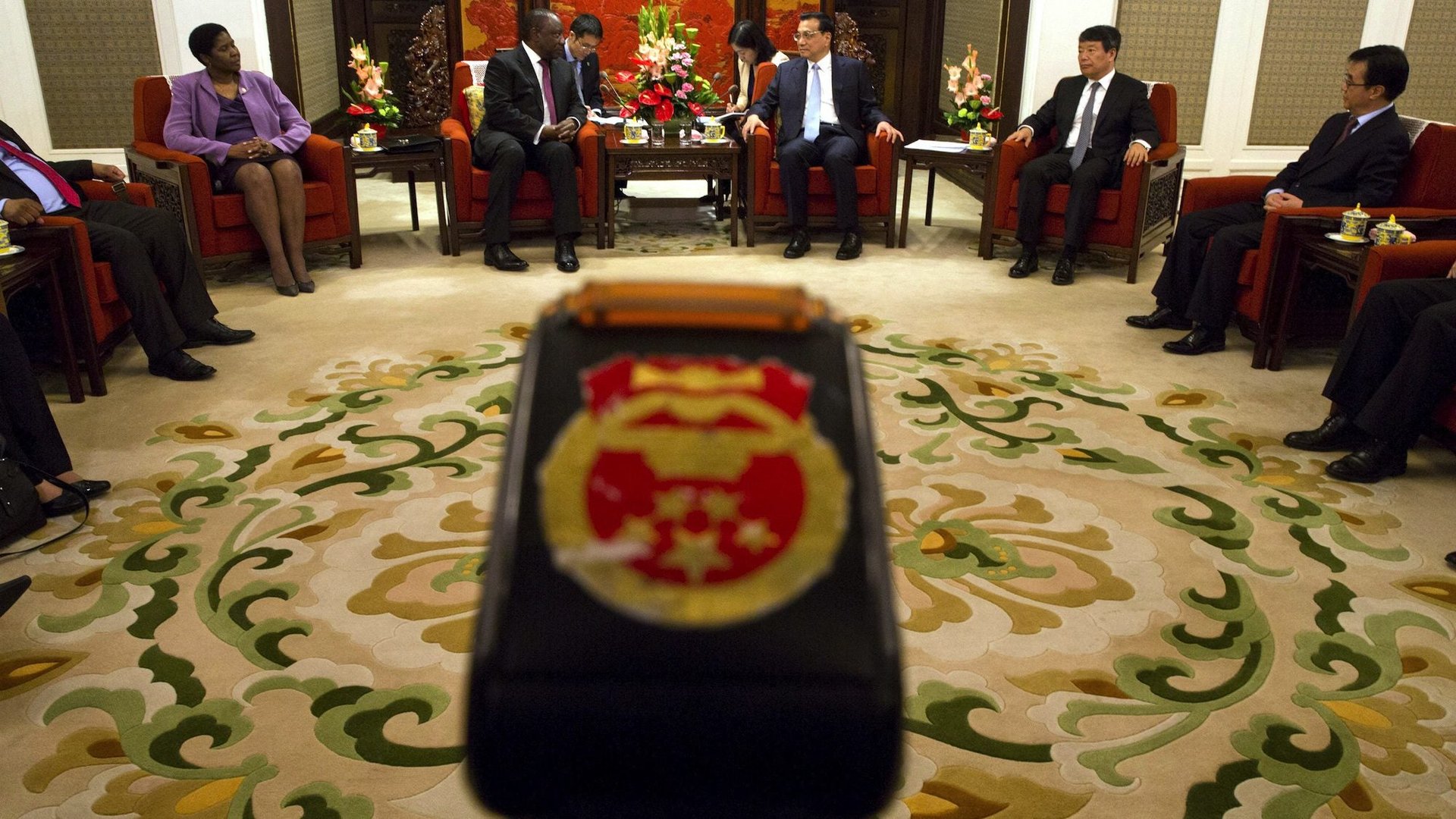

While China is a newer partner to Africa than the United States, it plays a powerful role as a counterexample. Many African governments see China as an model of a country that managed to develop without adopting American-style political systems. Until China came along, African countries were, (and still are,) prodded to follow Western ideas of democracy and civil society, as a gateway to modernity and development.

Chinese development presents a different narrative, one that some African governments interested in building centralized power, have eagerly embraced. The idea of the United States as the guardian of liberal values against powers like China, a story with echoes in the Cold War, might now be upended by the election of Trump to the US presidency. China’s counter-narrative of booming development guided by a strong centralized state is likely to become that much more appealing to politicians who want to believe in state power anyway.

We still don’t know what a Trump presidency will actually look like, especially as it relates to Africa. However, the president elect’s outspoken antipathy to traditional human rights principles—including his threats to prosecute his opponent Hillary Clinton after the election, his plan to build a wall between the US and Mexico, and his gleeful promises to ‘bomb the shit out of ISIS’— don’t fit the picture US public diplomacy has so far liked to present in Africa.

In this sense, the Trump presidency could herald the end of the binary pull between the US and China that we have seen in Africa over the last 15 years. The traditional narrative about the US and China’s role in Africa, presented by the US government, has been a choice between US-style development via liberal human rights and China-style authoritarianism.

In 2011, Clinton warned the continent against “new colonialism” in a not-so-veiled jab at China. Speaking in Ethiopia last year, President Obama said, “Economic relationships can’t simply be about building countries’ infrastructure with foreign labor or extracting Africa’s natural resources.” These coded statements weren’t only aimed at throwing shade at China. They were also meant to position the US as Africa’s only trustworthy partner.

Yet, America’s model of development and democracy has already suffered some setbacks on the continent, even before the election. When the US government talks about the US as a human rights champion in Africa, officials only seem to take into account official diplomatic messaging. Other realities, like the rapid militarization of the US presence in Africa, go unmentioned.

US diplomats also don’t seem to realize that Africans have access to the internet. When presenting itself as a human rights paragon, they don’t completely grasp how images of black Americans being targeted by the police play in Africa. Africans are keen consumers of African-American media, and they are well aware of debates about racism and what it means to be black in America.

As part of a recent class on national image, I asked my students, all young black women, where they would take an all-expenses paid vacation. Not one out of the group of 10 said the US. When I asked why no one wanted to go to New York or Los Angeles, they all said that when they imagine themselves in the United States, they think of being hassled by racist American cops. “America just isn’t for us,” one said.

If president Trump follows through on some of the promises made during his campaign, Africans will find the ideal of American democracy a lot harder to share. This would further muddy the idea that in terms of both an ally and a development model, Africa has to choose between a democratic superpower and an authoritarian one. If both superpowers come to seem equally iffy on human rights, governance and civil society, then Africa’s choice of a development model will be more driven by these powers’ recent track records on economic development.

On these terms China is far more appealing. China’s growth still outstrips that of the US, and it has been funding infrastructure left and right in Africa. Meanwhile, the Obama administration’s Africa initiatives have been few and far between. It remains unclear how much of his biggest projects, such as Power Africa, have actually been implemented.

However, much of America’s global power lies in its grip on our collective imagination. This means that while president Trump might alienate Africans, American citizens’ reaction to his actions might draw them back in. Popular resistance in America against racism and mis-administration won’t go unnoticed in Africa. Remember, Africans know a thing or two about living under corrupt leaders. How Americans resist, or not, will be keenly watched.

This article was written as part of the China Africa Project, a multimedia online resource dedicated to exploring China’s growing engagement with Africa.