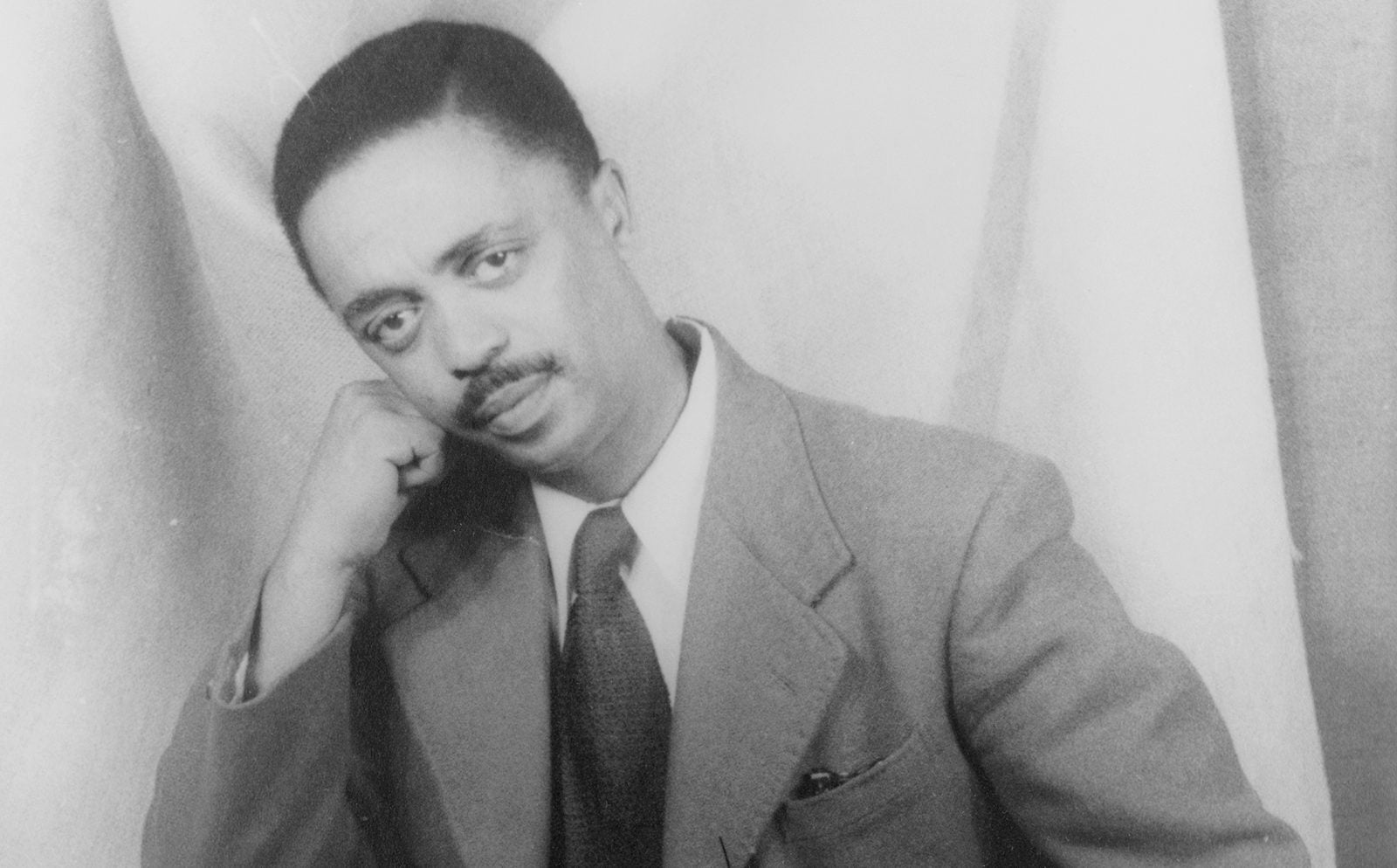

One of South Africa’s literary giants still remains hidden by apartheid’s cultural bans

Peter Abrahams’ name was mentioned in the same breath as South African literary icons as Alan Paton and Nadine Gordimer, and yet his death has almost gone unnoticed in his native land.

Peter Abrahams’ name was mentioned in the same breath as South African literary icons as Alan Paton and Nadine Gordimer, and yet his death has almost gone unnoticed in his native land.

Abrahams’ literature and journalism recorded the frustration and strain of ordinary South Africans under apartheid, but the system of apartheid ensured that Abrahams work was kept away from the majority of his people.

Abrahams is one of many authors, musicians and filmmakers whose work was banned by a voracious and absurd campaign to mute any voices that could challenge apartheid, sometimes going to ridiculous ends like banning the classic Black Beauty because of its title. People were banned too, including Stevie Wonder and Pink Floyd. While these works have been unbanned, many of the less prominent artists remain unknown to a generation.

Abrahams died at 97 in his adopted home Jamaica on Jan. 18, and while his obituary ran in newspapers like the Washington Post and the New York Times, few at home noticed. Former president Thabo Mbeki released a statement imploring young South Africans to read Abrahams, while commentator J. Brooks Spector decried the country’s failure to celebrate the first black South African novelist published internationally.

Born Peter Henry Abrahams Deras in Johannesburg in 1919 to an Ethiopian father and a mixed-race mother, Abrahams was first captivated by storytelling when a white woman he worked for read Shakespeare’s Othello to him at the age of 11. As a young adult he devoured African American literature as well as Marxist-Socialist writing.

His first novel Mine Boy told the story of a Xuma, a young black man who leaves his rural home to work underground in Johannesburg’s while he struggles under segregation. Abrahams went on to document life under apartheid, but fled the country’s racial repression at the age of 20. The Path of Thunder (1948), A Wreath for Udomo (1956) and many others followed. Abrahams’ work was also non-fiction, releasing a reporting book after a brief trip back home in 1952.

“I am emotionally involved in South Africa. Africa is my beat. If I am ever liberated from this bondage of racialism, there are some things much more exciting to me, objectively, to write about,” Abrahams told the Wilson Library Bulletin in 1957. “But this world has such a social orientation, and I am involved in this world and I can’t cut myself off.”

In Jamaica he became a known personality and his death was covered widely. There he lived on a hill with his wife Daphne, becoming an editor and radio commentator. He was also instrumental in building support for Africa’s anti-colonial movement, connecting with Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta and Trinidadian pan-Africanist George Padmore. Abrahams never returned, and when the country was free, so was he.

“I became a whole person when I finally put away the exile’s little packed suitcase. When Mandela came out of jail and when apartheid ended, I ceased to have this burden of South Africa. I shed it,” he wrote.

Abrahams was awarded national orders in 2008 and was briefly mentioned in the local press, but he remains part of an undiscovered treasure trove for many in the country he so loved.