One of Africa’s largest art collections is under threat

No one would store a Rodin, Monet, Picasso or Goya under a leaky roof, and yet the Johannesburg Art Gallery’s impressive art collection has had to do just that. The landmark museum has fallen victim to neglect and crime, despite the efforts of art lovers to keep the more than a century-old institution relevant in an ever-changing city.

No one would store a Rodin, Monet, Picasso or Goya under a leaky roof, and yet the Johannesburg Art Gallery’s impressive art collection has had to do just that. The landmark museum has fallen victim to neglect and crime, despite the efforts of art lovers to keep the more than a century-old institution relevant in an ever-changing city.

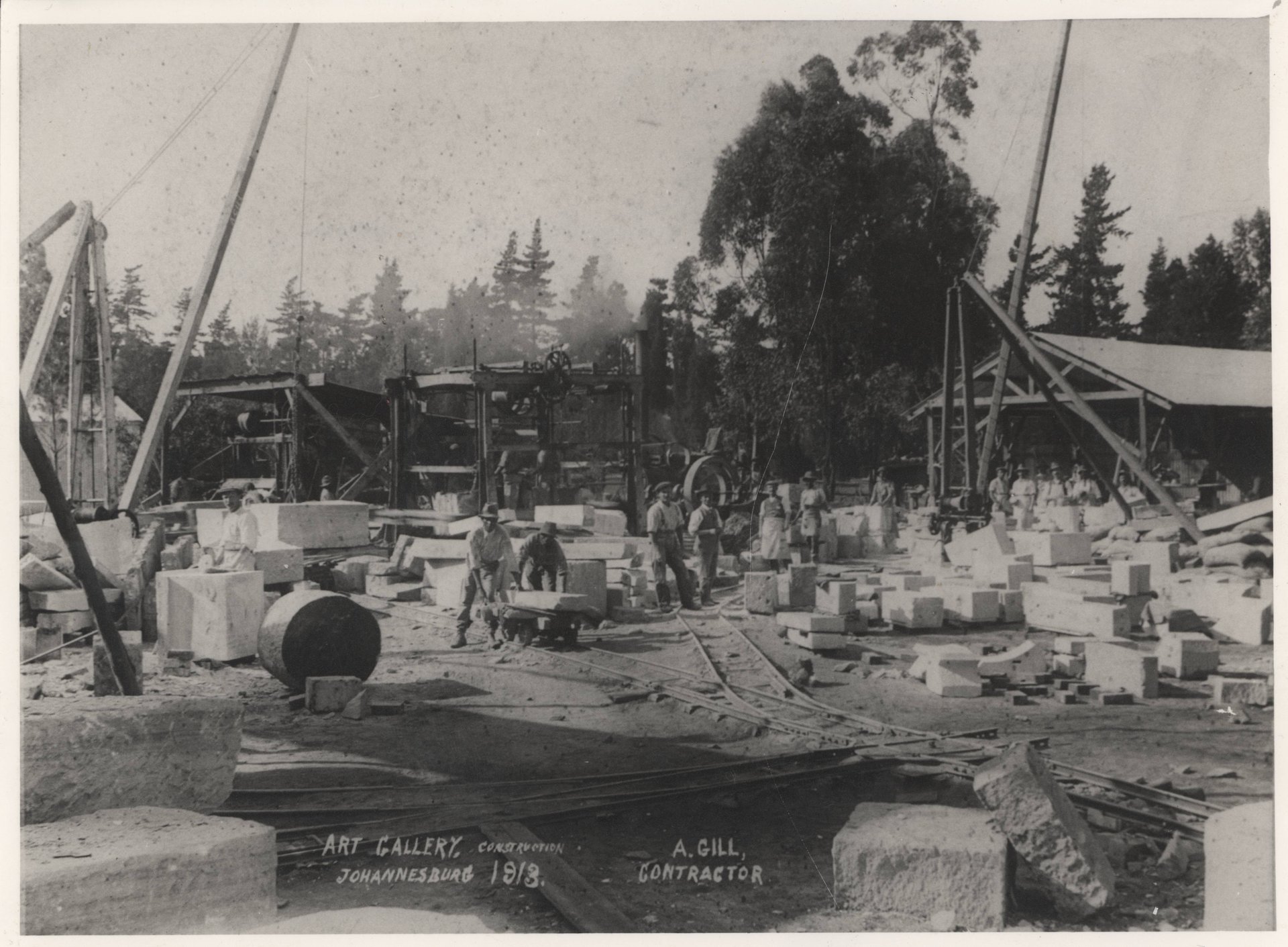

The museum was closed temporarily this month, after heavy rain damaged the roof that has leaked since 1989. For a few years now, thieves have stolen the copper finishing on the building, weakening it’s structure. The city tried to renovate it in time for the centenary celebrations in 2015 but shoddy workmanship led to the gallery’s current forced closure and safety hazard concerns less than two years later.

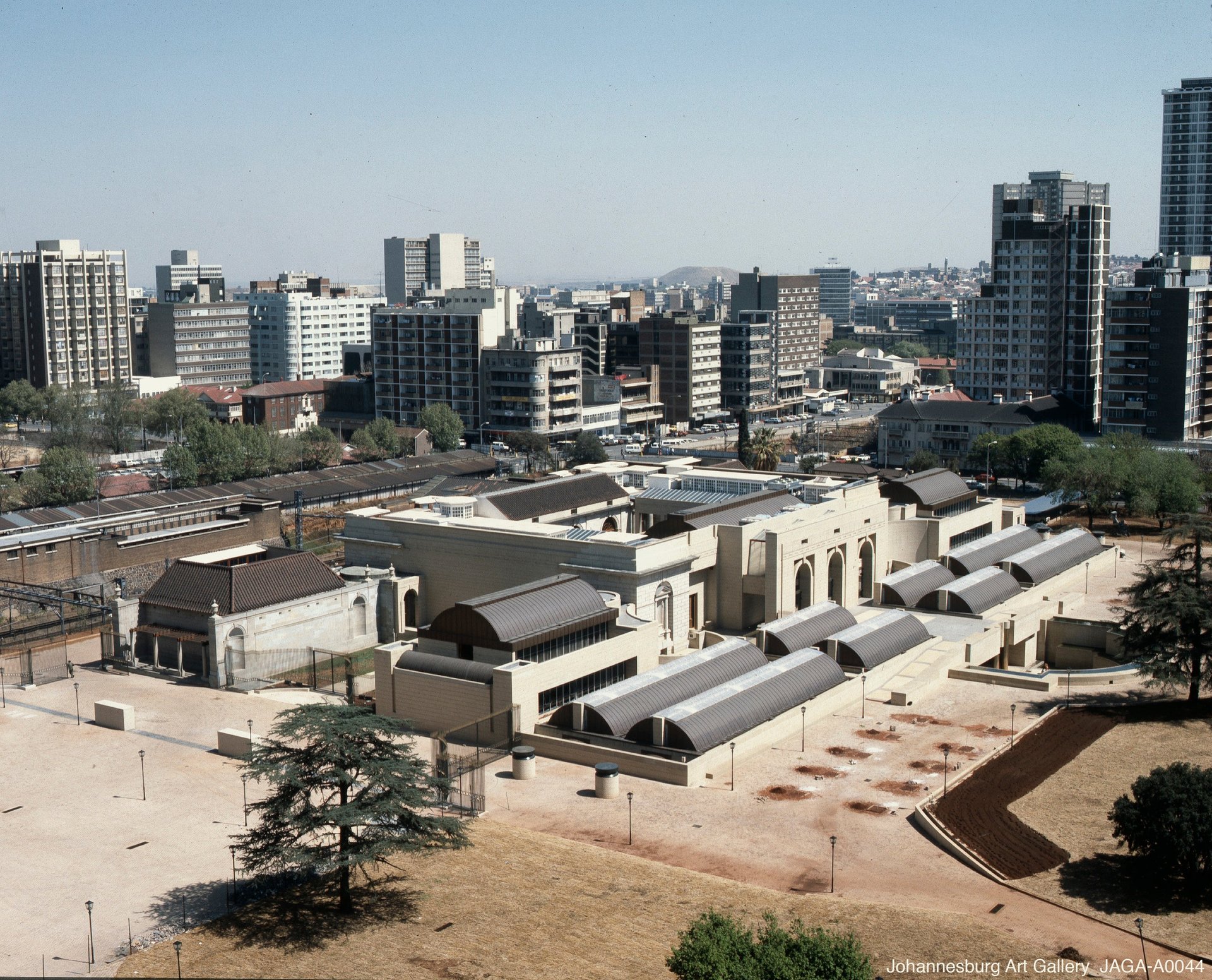

All around the Johannesburg Art Gallery, the city has changed drastically: the Victorian and Edwardian homes of an old mining town gave way to post-war high rises that turned into vertical slums. The neighborhood has remained vibrant and cosmopolitan, but its reputation has been blighted by a lawlessness that made the inner-city a no-go zone for those who could afford it.

Gentrification, redevelopment and stricter enforcement of bylaws have cleaned up much of the inner-city. Today, the gallery finds itself in an area swarming with foot traffic, with bus, train and taxis passing by, but the reputation is hard to shake.

“I think it’s in exactly the kind of place a public institution should be,” said Tara Weber, the gallery’s registrar, explaining that the gallery’s relationship with its community matters more than the ever-changing trends of real estate. They’re also planning to take the gallery outside, taking part of the collection or reproductions on a tour to communities and schools as a mobile museum.

“Especially when you have a historical building like this that might have references to western history, it’s important that we show more contemporary and pan-African art,” Weber told Quartz.

The previous administration left the facility in shambles,” said Councilor Nonhlanhla Sifumba. “Nothing was done to upgrade and maintain the facility despite millions being allocated for this purpose prior to its 2015 centenary celebrations.”

Johannesburg Art Gallery describes its collection as the largest in Africa. It says at any given time, only 10% of the collection is on display in the galleries various wings, and the research library is said to be an art student’s dream.

Inside the sandstone gallery walls is a collection that spans continents and genres and should be better protected. Alongside the European greats are South African masters Gerard Sekoto and Jacob Hendrik Pierneef.

Yet despite this heritage, the Johannesburg Art Gallery has suffered under neglect, relying on benefactors and outspoken art lovers like Marianne Fassler, a well-known South African fashion designer and one of the founding members of the Friends of JAG group.

“I just want it to become active again,” said Fassler. “It’s unbelievable what you can see there.”

Fassler is convinced that the last member of the mayor’s office in charge of the cities public museums and galleries has never set foot inside it. If she did she would have noticed the faulty phone lines, non-existent wifi and basic neglect. Fassler is optimistic about the change in management at the mayor’s office will be good for the gallery. She sees the leaky roof as a blessing in disguise—renewing her drive to recruit new Friends and remind Johannesburgers of the treasures inside the gallery’s parquet-floored wings.

Even if the repairs aren’t quite finished by May as planned, says Weber, the museum will open a wing to host the solo exhibition of Mozambican artist Ângela Ferreira, whose work deals with architecture and buildings that find themselves in difficult spaces.