Homegrown technology is being used to help millions at risk from a devastating famine in Africa

Two weeks ago, in Stockholm, Mohammed Omer and four of his friends gathered to talk about the biting drought ravaging their home country, Somalia. Beyond donating funds, the tech developers and social activists came together to discuss ideas to assist those in need of immediate relief. Eventually, they decided to use Ushahidi the Kenyan open source software to develop a platform that would allow responders to connect with drought victims.

Two weeks ago, in Stockholm, Mohammed Omer and four of his friends gathered to talk about the biting drought ravaging their home country, Somalia. Beyond donating funds, the tech developers and social activists came together to discuss ideas to assist those in need of immediate relief. Eventually, they decided to use Ushahidi the Kenyan open source software to develop a platform that would allow responders to connect with drought victims.

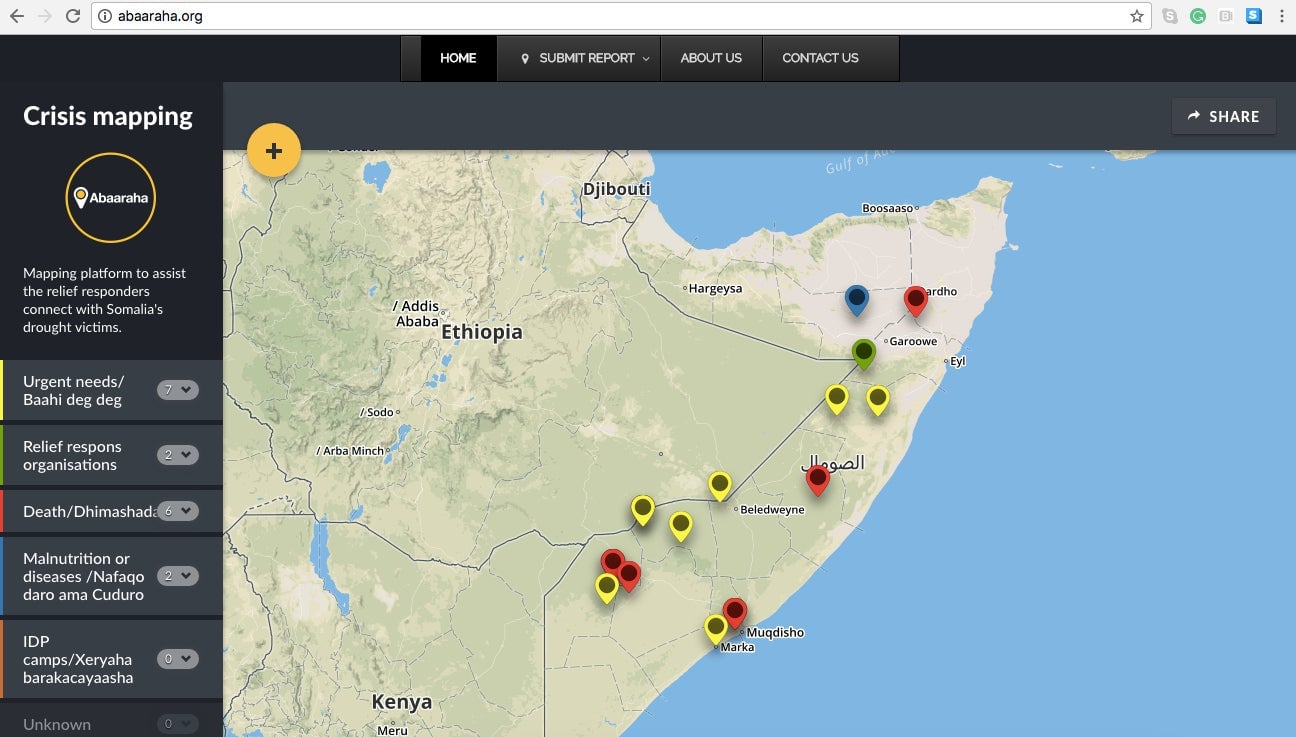

The result was Abaaraha (“drought” in Somali), a crowdsourcing platform that collects and verifies data through text, phone calls, email, and social media alerts. The web portal, which went live on Mar. 16, maps cases of malnutrition, disease outbreaks, and death. “There are no platforms that provide full information” with regards to the drought, says Omer. They’re “trying to fill that gap and to [help] coordinate the relief efforts that are taking place.”

An unprecedented crisis is currently gripping Somalia, South Sudan, Nigeria, and Yemen, threatening the lives of 20 million people, according to the United Nations (UN). More than 5 million people face acute food shortages in northeast Nigeria, and famine in parts of South Sudan threatens more than 7.5 million people. In Somalia, where cholera outbreaks have killed hundreds of people, the looming famine threatens 6.2 million—more than half the population. It threatens to bring back the grim reality of 2011, when 260,000 Somalis starved to death.

The UN has given its Food and Agriculture Organization a $22 million loan to help tackle the crisis. Yet, that’s a far cry from the $4.4 billion they need by July to stall Yemenis, Somalis, Nigerians and South Sudanese from dying. But, not waiting on donors, young African professionals both at home and in the diaspora are taking the initiative to connect, collaborate, and raise funds and relief materials to assuage those in need. Equipped with smartphones and access to the internet, they are especially using social media outlets to spread the news about the drought and create positive change.

While raising awareness and funds is a vital part of managing the famine crisis, tech platforms like Abraaraha and others also help authorities identify, track and efficiently respond to specific areas in need, and in turn, helping avert deaths or a humanitarian catastrophe.

Global traction

These collective efforts have started gaining global traction and drawing the attention of both governments and non-governmental agencies. Their efforts, in countries where governments are known to be slow-paced, inefficient and even corrupt, can prove to be the difference between life and death for hundreds of thousands at risk of hunger and disease.

Bukky Shonibare is an activist and social impact worker, who alongside a group of well-meaning Nigerians, launched Adopt-A-Camp in 2015. The collaborative effort focused on sourcing donations through a dedicated online portal to provide amenities to internally displaced persons (IDPs) in camps. With the northeast devastated by the Boko Haram insurgency over much of the past decade, thousands of Nigerians have been left homeless and remain in congested camps.

Adopt-A-Camp raised $28,000 last year (pdf, p. 8) and built two learning hubs for out-of-school kids as well as a health center and toilet facilities in Biu IDP camp, in Nigeria’s northeastern Borno state. Across the three IDP camps in which it operates, backed mainly by donations from individuals, Adopt-A-Camp says over 6,000 IDPs are now beneficiaries of its donations, which also include food and basic necessities, like clothes.

Hashtag fundraising

Twitter has especially been a critical tool to raise funds and build these virtual communities. After the hashtag Caawi Walaal (meaning “help a brother or a sister” in Somali) started circulating online, a group of volunteers got together to brand it and use it to sponsor 500 families living in drought-affected areas.

Their collective efforts raised more than $30,000 in total through mobile money transfers and a GoFundMe campaign. A one-day fundraising ceremony in Mogadishu also collected $15,000 in donations. Beyond Twitter, in Somaliland, friends and family members have also been forming groups on the instant messaging platform WhatsApp, urging each other to donate money and to sponsor hard-hit families.

Ahmed Ibrahim, one of the co-founders of the Walaal campaign, says the funds have allowed them to distribute food, medicine, and water in more than six regions across Somalia. “The biggest impact from all these collaborative efforts is that the information about the drought has helped spread all over,” Ibrahim said.

Celebrities all over the world, like Ben Stiller and NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick with help from Turkish Airlines, have joined the campaign to help Somalis facing starvation. The campaign, known as the Love Army for Somalia, has collected $2 million in less than a week .

In Nigeria, there have been similar social media-based fundraising efforts. Back in 2014, Modupe Odele, a lawyer now based in New York, went on a trip to northeast Nigeria. Gripped by the grim realities of residents whose lives had been devastated by the Boko Haram insurgency, Odele decided to start a campaign to donate blankets to IDPs. It started with one tweet, Odele says, but along with a group of interested people, the blanket drive has donated not only blankets but also other relief materials every month till date.

“It was more than a blanket drive, the goal was to draw people’s attention to what was going on in the northeast,” Odele says.

Also in Nigeria, Oghenekaro Omu set up Sanitary Aid for Nigerian Girls (SANG), a campaign to donate sanitary pads to “girls from low-income homes and the girls in the IDP camps.” More than giving them pads, Omu says the project will also focus on teaching the girls about sanitary hygiene in general.

Over-populated IDP camps have been struck by disease outbreaks, with young girls who are unable to access sanitary items, particularly at risk. Since launching the project, Omu says over 3,000 sanitary pads have been provided—all through social media donations. SANG has also snagged blue chip support: earlier this month, it announced a partnership with Microsoft.

Checks and balances

Ibrahim from Caawi Walaal says that some contributors have been worried about whether or not the monies could be misappropriated. He says they partnered with Somalia’s umbrella organization for private schools, who manage the funds under a subsidiary account. “We have ensured that transparency and documentation are followed to the letter, but again, that they should help us disperse the funds faster.”

In Nigeria, transparency presents a bigger challenge. Reports of IDP camp officials stealing and selling donated items have resulted in government-sanctioned probes. It’s not just lowly officials either: back in December, the Nigerian senate uncovered an $8 million relief fund fraud implicating a high ranking official in the presidency.

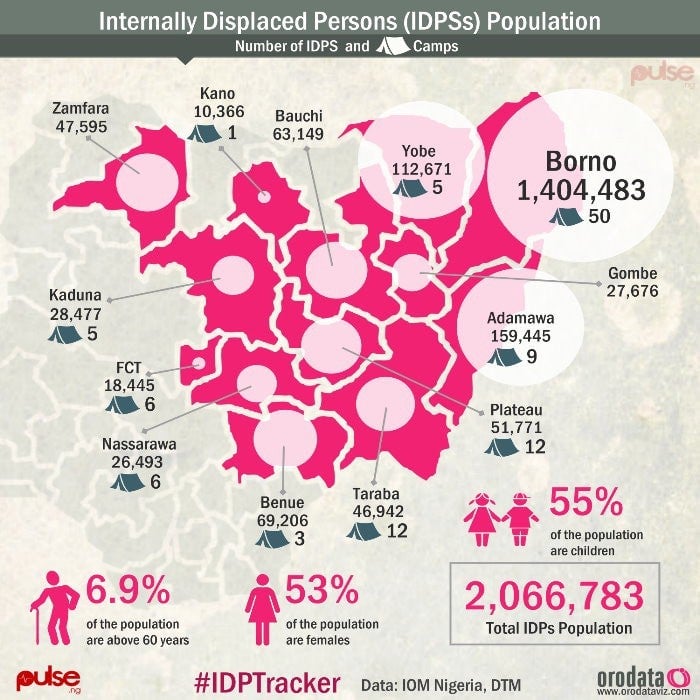

To check fraud, Orodata, a Lagos-based civic startup has created IDP Tracker, an online tool with which provides crucial information on camps for the internally displaced in Nigeria’s northeast. Blaise Aboh, the lead data analyst at Orodata, says data from IDP Tracker will boost transparency around relief operations and also help NGOs and government policy-makers understand the scale of the problem as well as make more informed decisions.