These photos show the Rwandans who fled Paul Kagame’s leadership

Twenty-three years ago, members of Rwanda’s Hutu majority tortured, raped, and killed some 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus in just about 100 days. It was all-consuming—the killers were not just members of the army and government-backed militias, but also neighbors and friends who turned on those they grew up and worked with.

Twenty-three years ago, members of Rwanda’s Hutu majority tortured, raped, and killed some 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus in just about 100 days. It was all-consuming—the killers were not just members of the army and government-backed militias, but also neighbors and friends who turned on those they grew up and worked with.

Since then, Rwanda has embarked on healing the wounds of the genocide through reconciliation, while not forgetting the tragedy; April 7 is an international day of reflection to remember the catastrophe. That’s come alongside strong development for Rwanda. In the past two decades, the landlocked east African nation has experienced strong economic growth, adopted technology as a tool for transformation, substantially reduced child mortality rates, and improved living conditions for its people.

But while president Paul Kagame (who has been in office since 2000, and essentially led the country as vice president and minister of defense from 1995-2000) is hailed for putting an end to the genocide and steering the country towards development, critics says his dominance over the country’s politics, and his repression of political opposition and press freedom, threaten to undermine the progress of the country. His strong-man politics, the harsh sentences meted out against former comrades, and the use of propaganda and the media to co-opt the masses, they say, all show that he is teetering from benevolence towards dictatorship.

In her latest collection of photos, Finnish photographer Miia Autio documents the stories of those Rwandans, Hutus mostly, who left to seek a better life in Europe because of the outcome and consequences of the genocide. Facing threats, and fearing arrests and torture after Kagame came to power, these Rwandans say they chose to live in exile.

Many of those photographed spoke about the pain of leaving their families, feeling alienated in their new adopted countries, struggling with integration and learning foreign languages, and missing the picturesque, hilly towns they grew up in. Autio decided not to share the names of her subjects, and some chose not to show their faces for fear of retaliation.

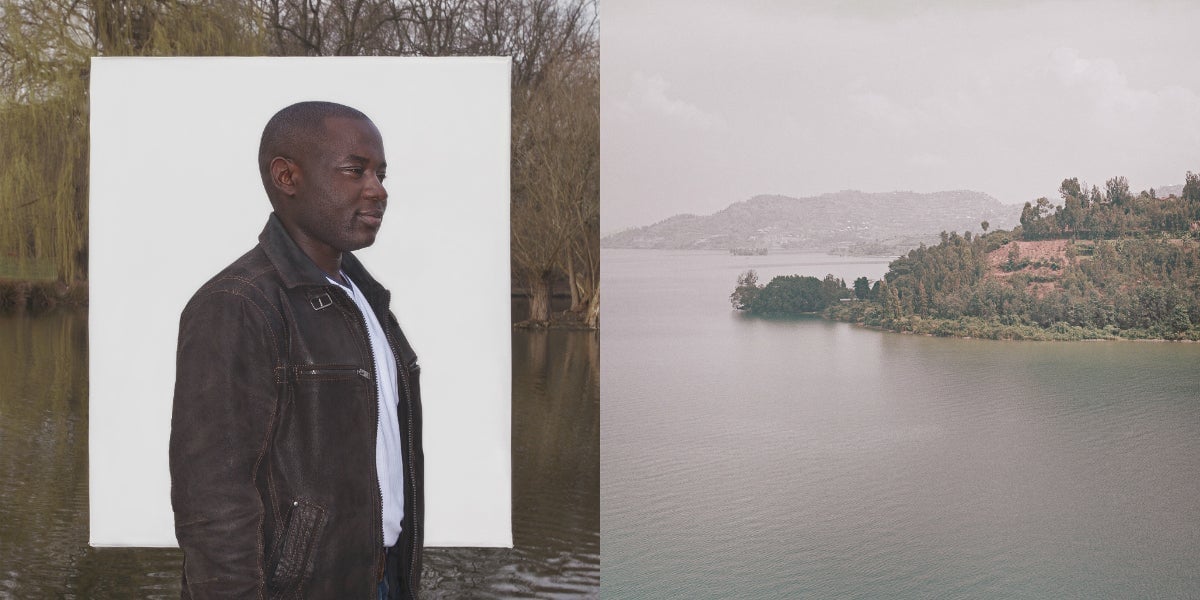

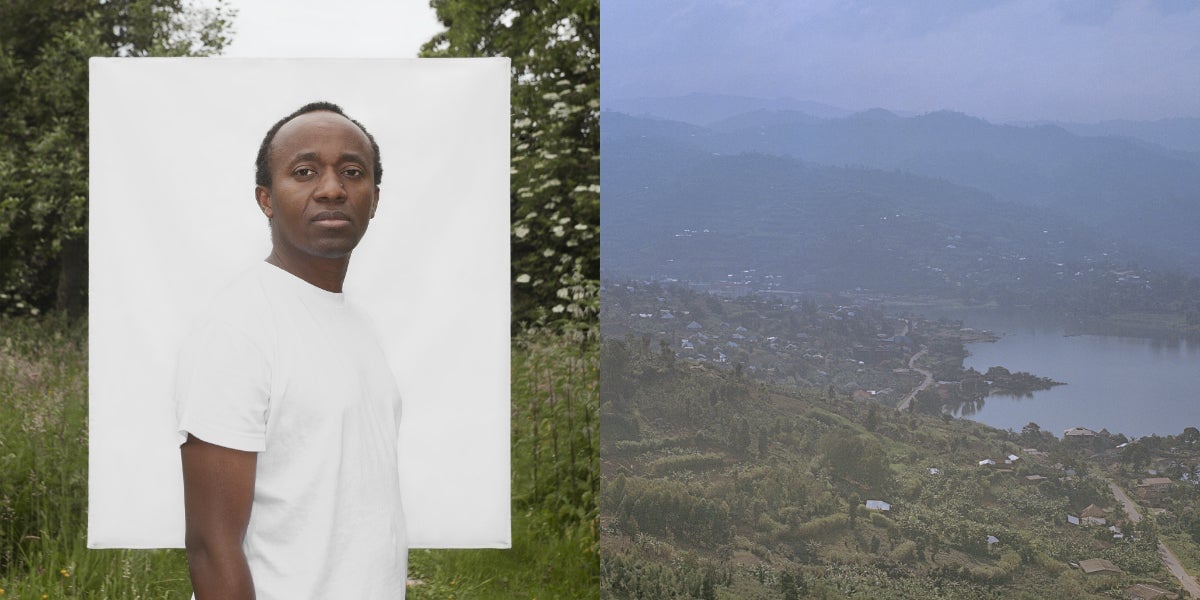

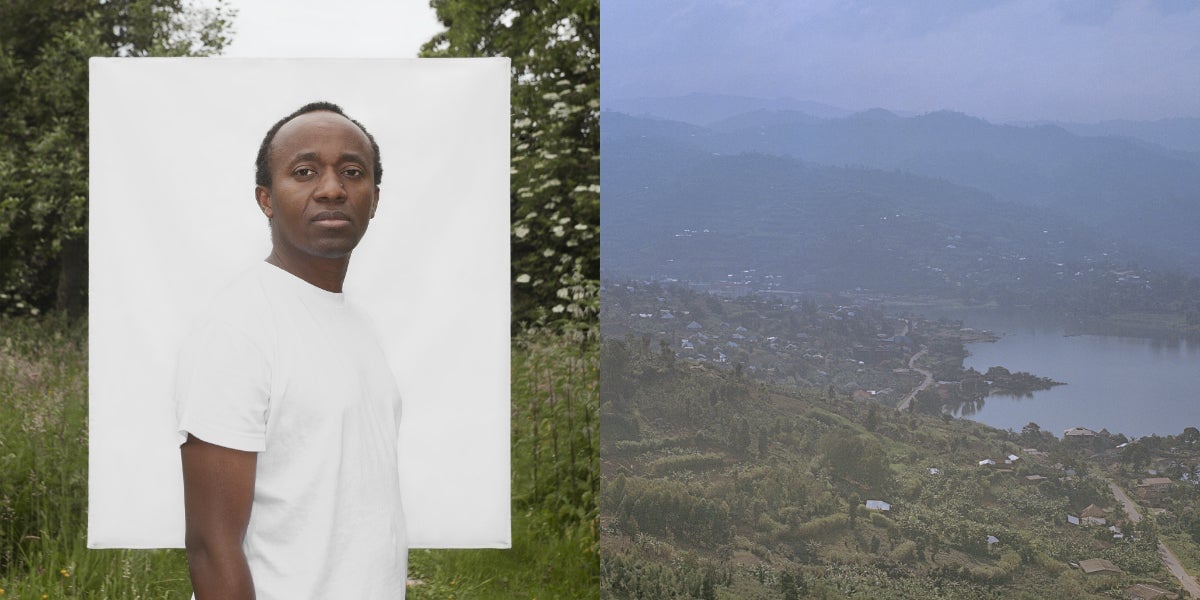

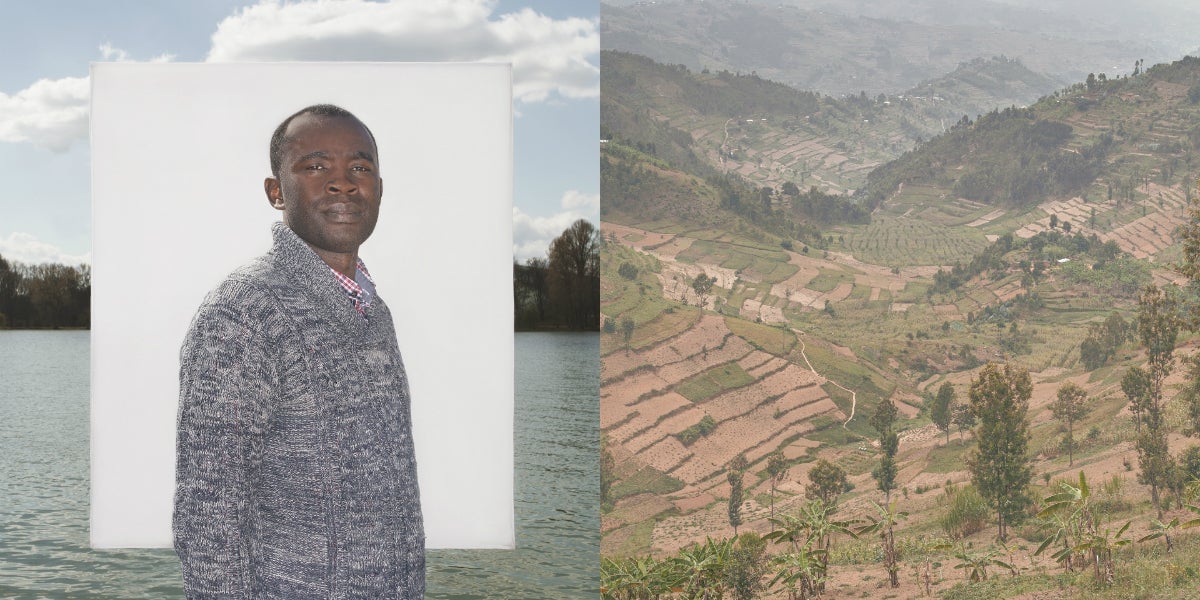

In the collection, titled “I called out for mountains, I heard them drumming,” Autio had her subjects stand in front of a landscape of their new homes—but with a large white rectangle between person and environment. She says it’s to symbolize the origin of the person and the memory of their former countries. She then traveled to Rwanda to photograph some of the landscapes her subjects had described to her, and juxtaposed those with the portraits.

“What pushed me to do this series was my personal interest in landscape and in the concept of home and nationality,” Autio tells Quartz. “The portraits and the landscapes together form many layers between the past and the present.”

The man in the photo above was born in Rambura and said he had to flee after his family members were killed in 1997. “I was fighting against the government first in civil society and later in politics. But the government was torturing and chasing me, and that’s why I had to leave.” The decision, he said, “was between life and death and I decided for life.”

The price for dissent in Rwanda is often high. Journalists like Anjan Sundaram have shown that post-genocide, espousing opposition ideas can lead to jail or death. The man photographed above, who now lives in Hanover, Germany, says he left because of “lack of freedom of speech” and thought. He says he wouldn’t feel safe going back to Rwanda because “if I criticize the government it could be bad for me.”

Some of those photographed said that they liked being citizens of European countries because “the government here supports everyone, including foreigners.” But others said they face discrimination in their new homes. The women in the photo above is originally from the Gacumbi district in Rwanda’s northern province. She said that while interviewing for a job once in her adopted European country, she was asked to turn on a computer. “They thought that I couldn’t open a computer,” she said.

But the one wish expressed most by those interviewed was to go back to “the paradise” of Rwanda. “It’s not depression, but it’s kind of a depression to be homesick,” one said.