France is giving citizenship to the African soldiers who fought its wars over 50 years ago

For most of the 20th century, France recruited, usually forcibly, men from its colonies in Africa fight its battles around the world. From the first world war in 1914 to the Indochina wars and Algeria’s fight for independence in the 1950s and 1960s, hundreds of thousands of Africans soldiers fought under the French flag. They were called tirailleurs, or “sharpshooters,” a name to mock their limited training.

For most of the 20th century, France recruited, usually forcibly, men from its colonies in Africa fight its battles around the world. From the first world war in 1914 to the Indochina wars and Algeria’s fight for independence in the 1950s and 1960s, hundreds of thousands of Africans soldiers fought under the French flag. They were called tirailleurs, or “sharpshooters,” a name to mock their limited training.

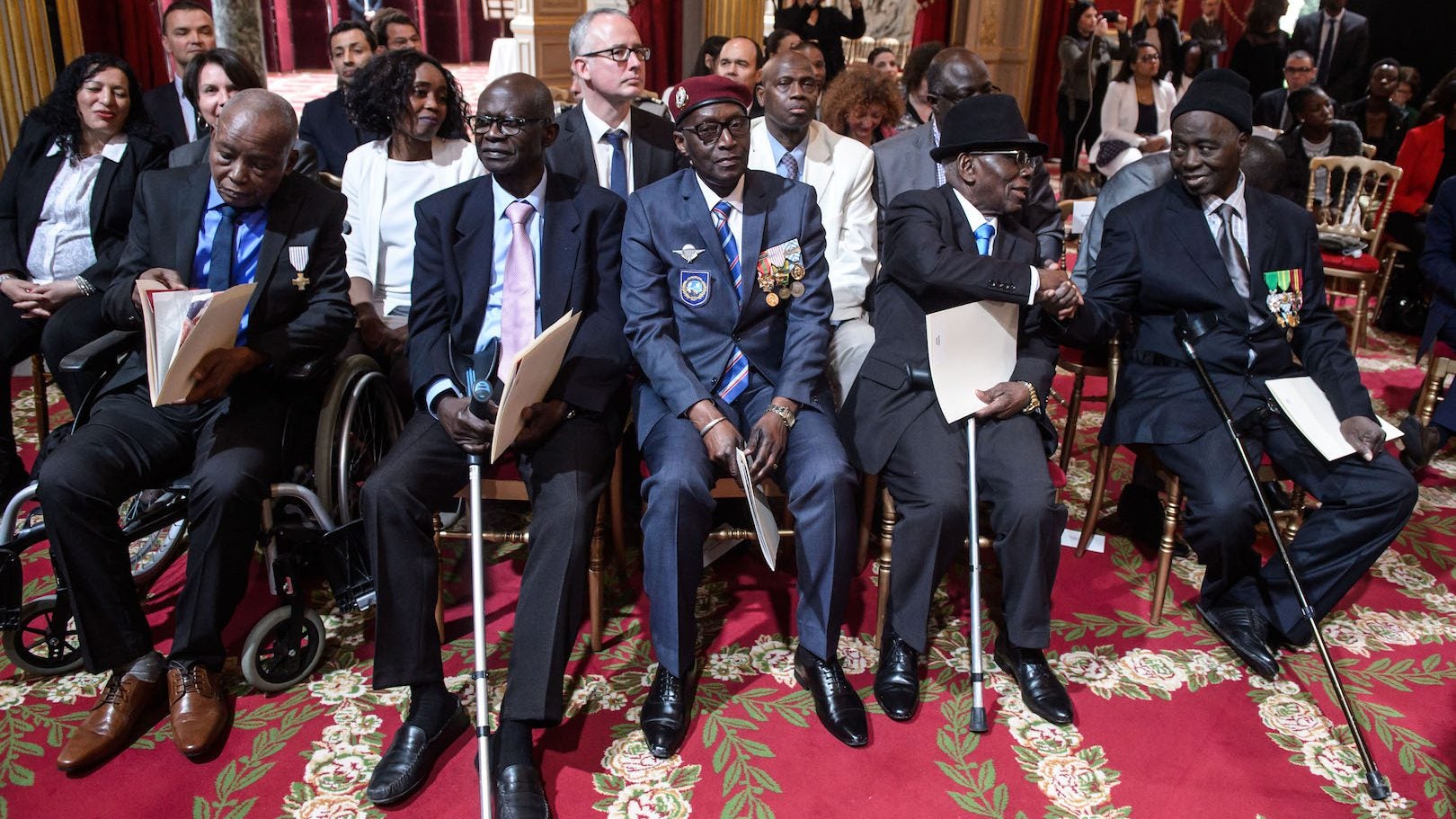

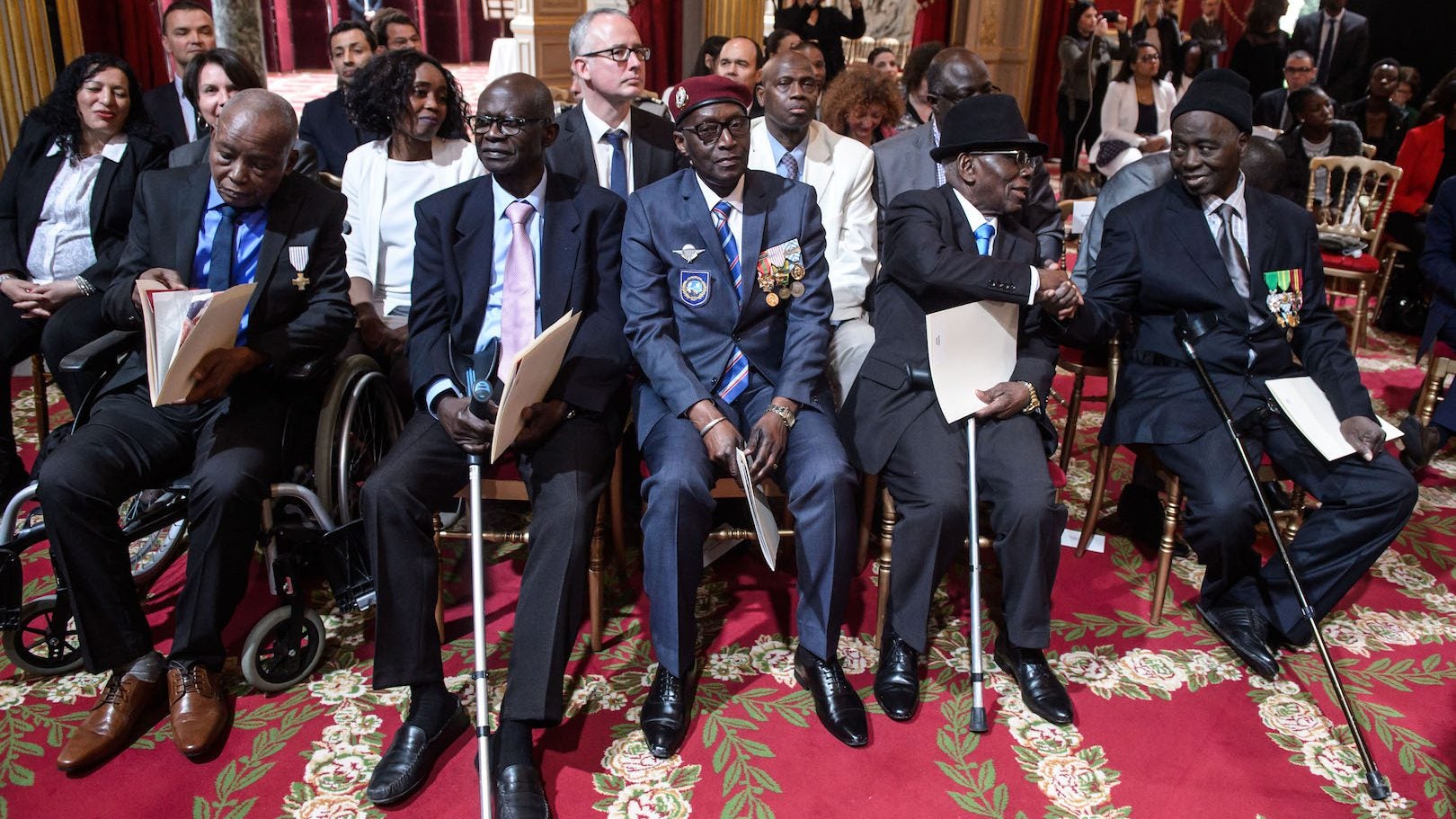

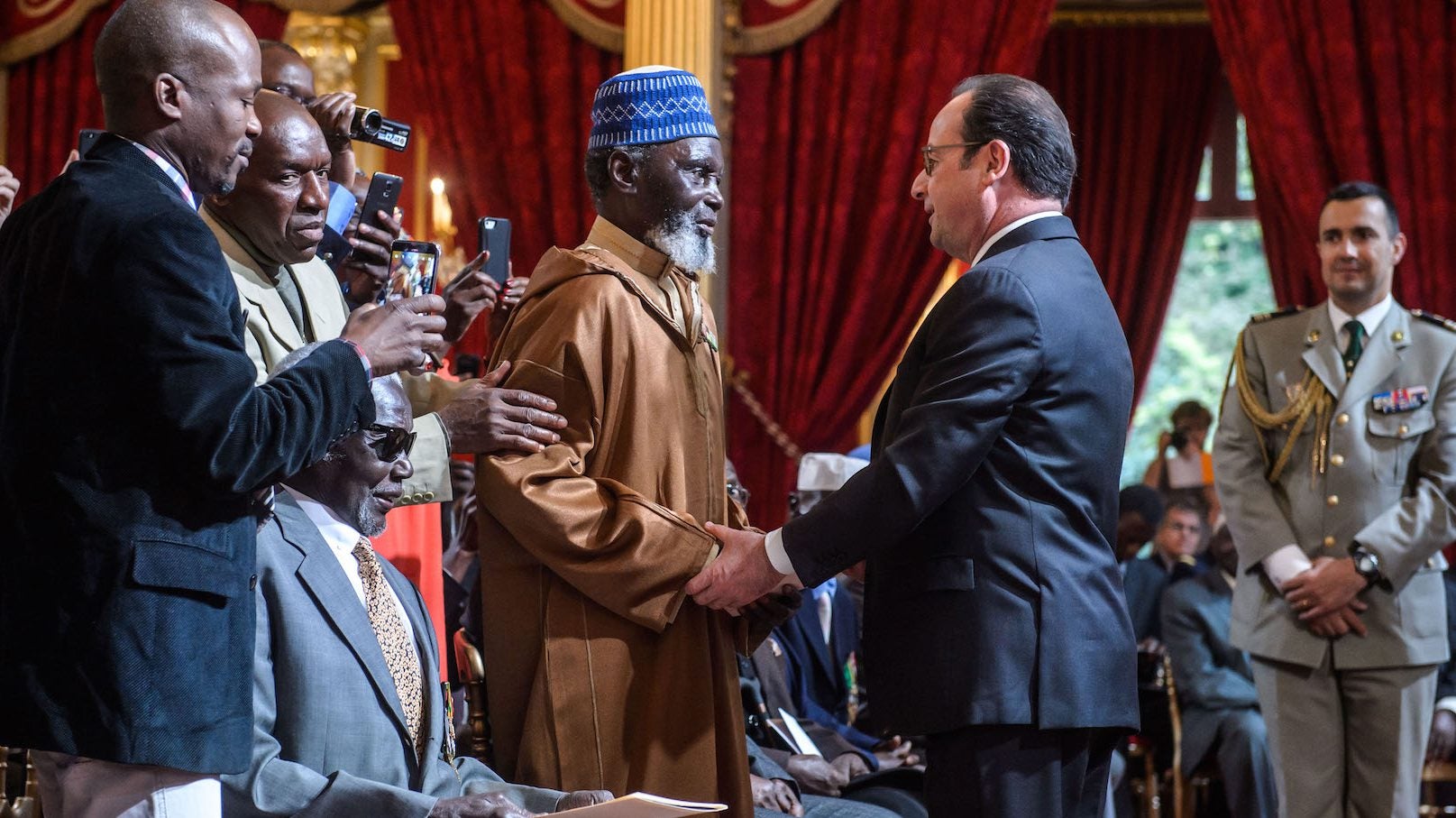

Decades later, 28 of these former soldiers were recognized in a ceremony on April 15 where they were given French citizenship. Many of them were from Senegal, a country that sent more than a third of all of its military- age men to France to fight during World War I.

“France is proud to welcome you, just as you were proud to carry its flag, the flag of freedom,” president Francois Hollande said at the ceremony in the Elysée Palace in Paris, adding that his country owes these men a “debt of blood.” The honored veterans were between the ages of 78 and 90.

The term is steeped in meaning. French colonial government and military used to say its colonial subjects owed the country a “blood tax” for its rule. Colonial soldiers responded by saying France owed them a “blood debt.”

Critics and leaders in former French colonies say that France has never really recognized or compensated the African soldiers that fought for the country. That has soured relations between African countries and France to this day.

“There is a long history there, and it includes racism and exploitation, and even violence when soldiers advocated for better treatment and pay that they thought was rightfully theirs,” says Richard Fogarty, a historian of modern France at the University of Albany in New York.

A group of West African soldiers stationed at camp in Thiaroye, Senegal, mutinied in 1944, demanding equal pay and the same treatment as their French counterparts. French soldiers fired on them, killing up to 400 men. Their mass grave still hasn’t been found.

After African colonies gained independence in the 1960s, France froze military pensions, citing cheaper living costs in Africa. While a French military veteran received €690 a month in 2006 (about $850 then), a sub-Saharan African or North African soldier got about €61. Former colonial solders were allowed to stay in France but could only go home for three months a year.

Over the past few decades, activists have gained some ground. The 2006 French film Indigènes, about a group of North African soldiers in France during World War II, dramatized the contributions of colonial soldiers in France’s liberation. More than half of French forces in Italy and France between 1943 and 1944 came from African colonies, and at least 40,000 died.

After seeing the film, then president Jacques Chirac promised to “do something” to honor these soldiers. In 2010, France granted full military pensions to 30,000 surviving colonial veterans from Africa.

Today, those that have been given citizenship can now travel freely between France and their homes in Africa. Aissatou Seck, a deputy mayor of a suburb in Paris who has been campaigning for the rights of African veterans, says there are hundreds of citizenship applications that Hollande has promised to process.

Whether that will be enough is unclear. “I’m not sure France can ever fully repay that debt, but these moves to try to do so are certainly better than nothing,” says Fogarty.