Ethiopia’s humans rights problems may tank its ambition to become a global apparel center

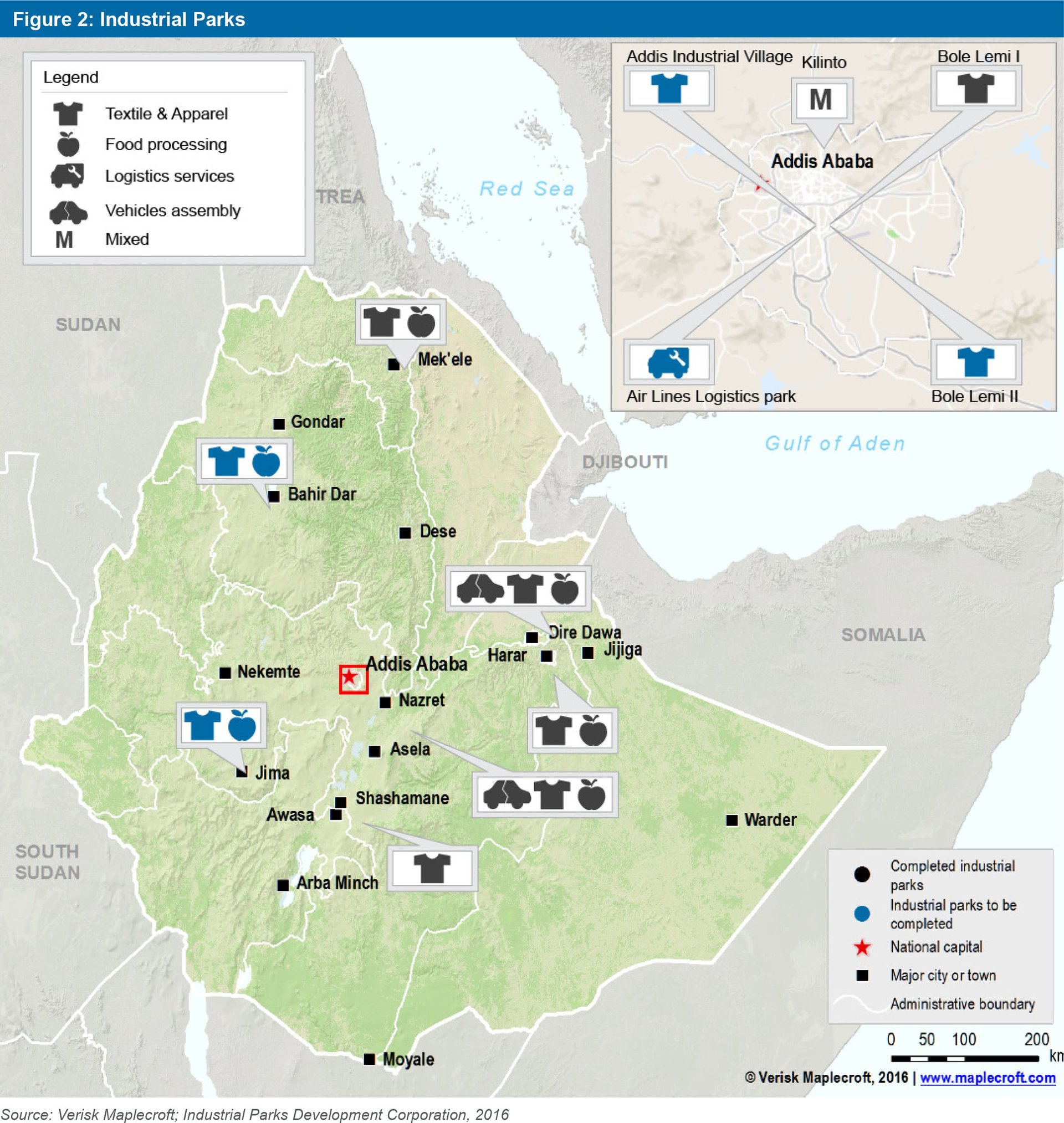

Ethiopia wants companies that make clothes to view it as one of the world’s most hospitable places to operate. Low employee wages and cheap power have led foreign companies to gravitate towards the Horn of Africa nation in recent years. The government recognizes the strategic importance of garment and textile making, and has continued to invest in the sector by constructing large industrial parks like the Hawassa Industrial Park.

Ethiopia wants companies that make clothes to view it as one of the world’s most hospitable places to operate. Low employee wages and cheap power have led foreign companies to gravitate towards the Horn of Africa nation in recent years. The government recognizes the strategic importance of garment and textile making, and has continued to invest in the sector by constructing large industrial parks like the Hawassa Industrial Park.

But its land and human rights problems could jeopardize that ambition, according to a new report from risk consultancy firm Verisk Maplecroft. Protests over land reform and political participation have rocked the country since 2015, leading to the reported death of hundreds of people and the detention of tens of thousands of others.

“The sector remains exposed to a host of political, social and environmental risks,” says Emma Gordon, a senior Africa analyst with Verisk. And “many of these issues are unlikely to be resolved over the coming five to ten years.”

These concerns could affect the cotton industry, and limit the opportunity to expand sustainable production. The persistence of child labor, water pollution, the exposure of workers to harmful chemicals, and the possibility of resumption of protests also pose a threat.

Ethiopia is one several east African countries—including Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania—identified as an important center for apparel sourcing. In a 2015 survey by global management company McKinsey, Ethiopia appeared as one of the top countries worldwide where companies wanted to source their garments from in the next five years.

Retail giants such as H&M, Primark, and Tesco have sourced or established textile factories in Ethiopia to diversify from Asian markets like China and Bangladesh. The footwear industry in Ethiopia is also growing, with the Huajian Group, the Chinese manufacturer that produces Ivanka Trump’s shoe brand, talking about plans to move production to Ethiopia.

These operations could be undermined by the political and social protests. The demonstrations began over plans to expand the capital Addis Ababa into neighboring towns and villages populated by members of the Oromo community—the country’s largest ethnic group. Although the Tigray-dominated government canceled the plans, protests escalated.

At the height of the protests in August and September 2016, flower farms and foreign commercial properties worth millions were burnt. The government responded by quashing the protests, shutting down the internet, and instituted a state of emergency in October that has lasted to date.

Gordon says that given that the “underlying drivers” of the protests have not been addressed, it is “highly likely that similar protests will erupt again.”

Land problems are also expected to intensify as drought ravages the country. Last week, the government announced that 7.7 million people were in need of emergency food aid. While the economy depends on agriculture, just 5% of the country’s land is irrigated, according to the United States Agency for International Development. The competition over fertile land as well as the government’s controversial plan to lease large swaths of land to foreign investors and private interests could jeopardize prospects for companies interested in doing business in Ethiopia.

“Investors are likely to become increasingly unpopular in the communities that they rely on for both their security and their workforces,” Gordon said.