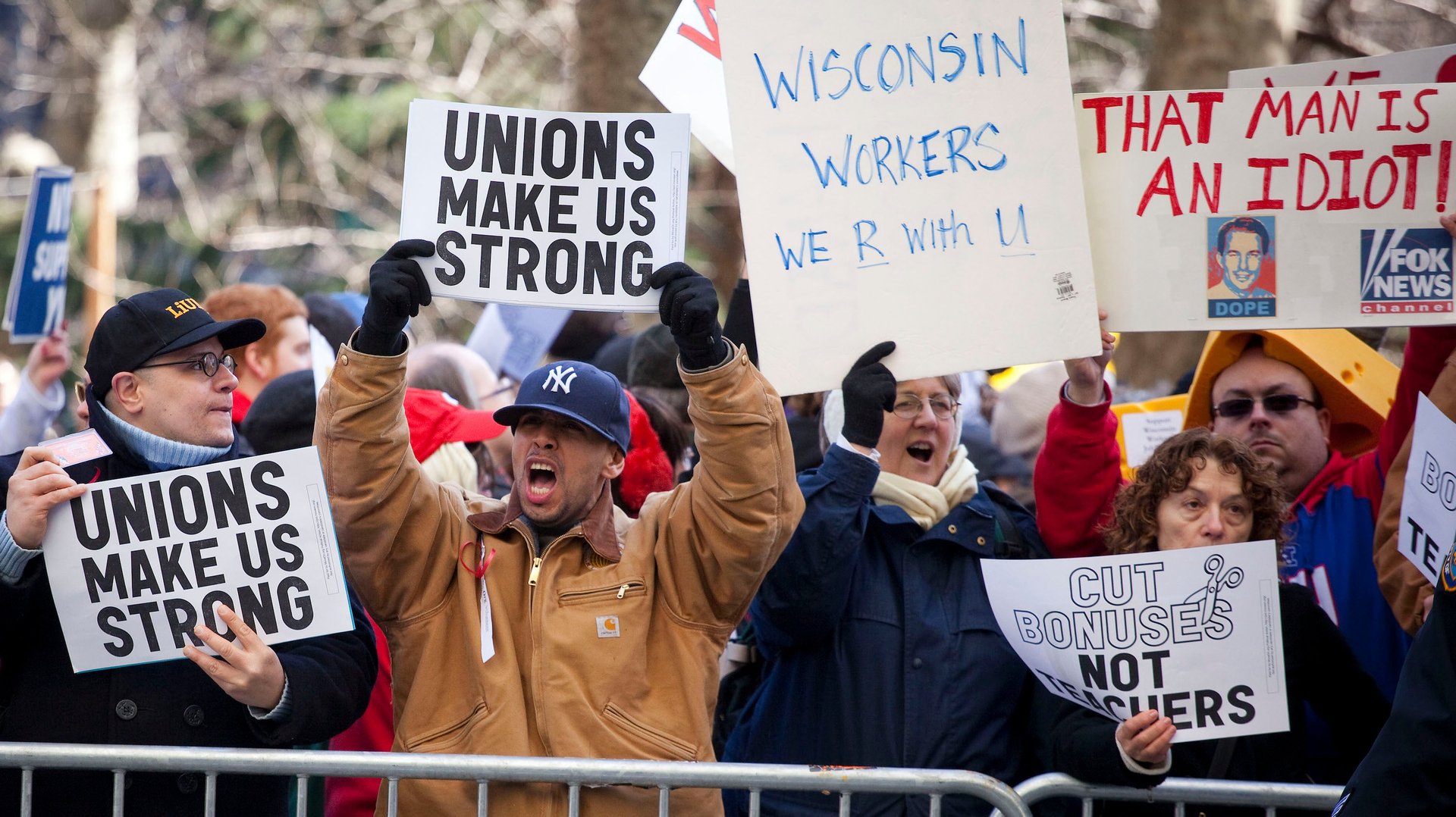

Are unions responsible for the decline of unions?

A new report argues that unions are sitting on profits rather than spending money on organizing workers.

The US labor movement has a lot of momentum these days—but there are still far fewer unionized workers than there used to be. Back in 1983, when the Bureau of Labor Statistics first began keeping track, 20% of American workers were unionized. By 2010, that number had fallen to 12%; in 2021, it dwindled to 10%.

Lots of factors have combined to chip away at the power of US unions over the decades, among them anti-union legislation, a robust anti-union consulting industry, and weak penalties for companies that violate labor laws. But a new report argues that unions have further contributed to their own decline by sitting on money rather than spending funds on organizing workers.

Why don’t unions spend more money on organizing?

The report from Radish Research, a firm that conducts research both on and for the labor movement, draws primarily on annual financial reports submitted by more than 13,000 unions to the US labor department as well as data from the US Census Bureau and other public sources. It finds that collectively, organized labor had a surplus of $2.7 billion in 2020, having brought in $18.3 billion in revenue and spent $15.6 billion on operating expenses. Such robust profits were not atypical: In the years since 2010, unions have had an average annual surplus of $1.7 billion.

That money could have gone toward hiring tens of thousands of organizers and funding smaller independent unions like the Amazon Labor Union, the report argues. But instead, unions largely opted for an approach known as “Fortress Unionism,” which involves “defending existing strongholds of union power, and avoiding costly and lengthy organizing drives in largely nonunion sectors until labor law is reformed and/or workers signal increased militancy,” it says.

In other words, unions seem to be wary of spending money on expensive organizing campaigns that may not pay off. According to the report, that’s made them complicit in the ongoing erosion of unionized workers—particularly because going on the offense might actually put pressure on politicians to bring about the labor law reforms that unions want.

Quartz reached out to several unions on the report’s findings, but none provided comment.

The report notes a few important caveats. For one thing, unions’ financial reports don’t break down how much money they spend on organizing specifically. But “large-scale investments in organizing would have been reflected in higher spending rates, increases in staff rather than reductions, the running of deficits rather than surpluses, and a reduction in net assets as labor used its cash on the balance sheet to finance spending on organizing,” the report explains.

Also, not all public-sector labor unions are required to submit financial reports to the Labor Department, and the reports are not organized like corporate financial statements, instead simply listing cash receipts and cash disbursements. Radish Report reorganized the unions’ financial statements to better resemble a balance sheet in order to interpret their spending.