Let's talk about that pesky debt ceiling

Why does Congress need to keep raising the country's borrowing limit?

A version of this article originally appeared in Quartz’s members-only Weekend Brief newsletter. Quartz members get access to exclusive newsletters and more. Sign up here.

Alexander Hamilton, whose financial acumen financed George Washington’s army, and very likely paved the way to win the American Revolution, was a big fan of the national debt. “A national debt, if it is not excessive, will be to us a national blessing,” Hamilton wrote. Not only does it let a country finance growth by borrowing to stimulate future revenue, but a national debt also gives lenders a stake in the country’s success.

And yet, almost every December, Congress goes down to the wire over whether or not to raise the limit — known as the debt ceiling — on the ability of the United States government to go into debt and borrow enough money to pay for the spending Congress has already authorized. A couple of weeks ago, after Democrats and Republicans had agreed on a way to finance the government for the next few months and raise the debt ceiling, Elon Musk—swiftly followed by Donald Trump—torpedoed the agreement. Why? Largely, said Trump, because he wanted Congress to raise the debt ceiling even more. This move, which many saw as counterintuitive, would have let Trump cut taxes when he got into office, but instead of cutting spending alongside the taxes, he’d be able to keep borrowing to finance the tax cuts.

Under the deal passed just as Congress skedaddled from Washington before the end of the year, the ceiling will be exceeded sometime between January 14 and January 23. If the new Congress doesn’t agree to raise the ceiling—and let the Treasury borrow more—then the government will have to take what Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen called “extraordinary measures.” In other words, decide which bills not to pay until Congress gets its game together and raises the ceiling.

So what exactly is the debt ceiling?

Many people often conflate the debt ceiling with the national debt and the budget deficit, notes Tyler Schipper, an associate professor of economics at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

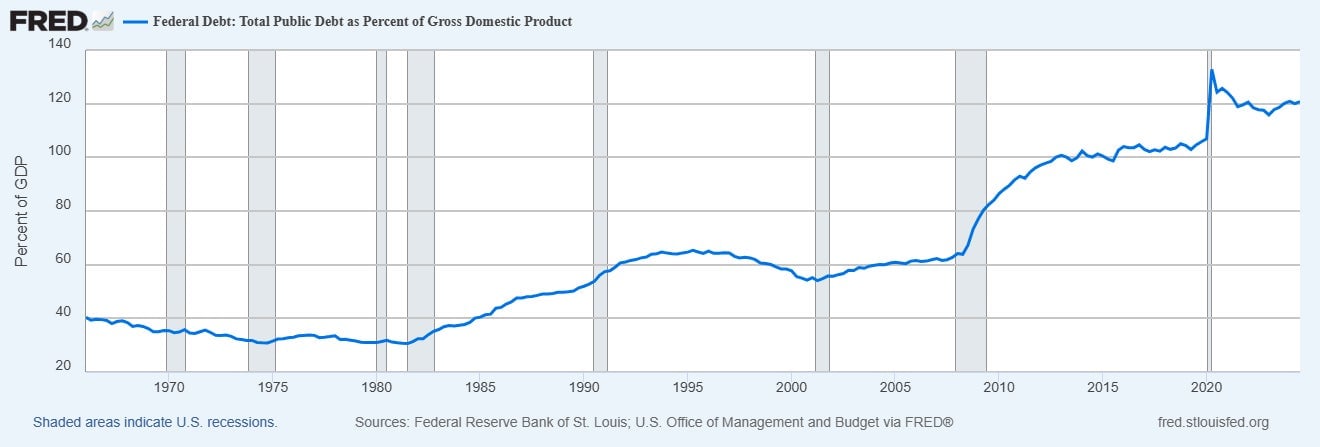

A deficit is when the government brings in less revenue (think taxes) than it spends each year, and the U.S. government has been running deficits for decades, with a short interruption in the Clinton Administration. Because we run deficits, the Treasury needs to borrow money by issuing debt (Treasury bills, bonds, and the like). The debt is the accumulation of this borrowing - about $36 trillion now. The debt ceiling is a cap on the borrowing authority of the U.S. Treasury. “To be clear,” said Schipper, “it’s not a cap on spending. Congress already voted to spend the money, and the President signed off. The debt ceiling just allows the U.S. government to pay its bills.”

Having a debt ceiling, particularly one that leads to a showdown every year, makes no sense, said Luke Tilley, chief economist at Wilmington Trust, an asset manager that’s part of M&T Bank. “Congress sets the debt limit, and they set spending, and they set taxation,” said Tilley. “And then Congress says, yeah, but you can’t borrow any more.” The only point to the debt limit, says Tilley, is that it forces everyone back to the table to negotiate.

In a 2023 survey by the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, 74% of the leading economists surveyed said that having to periodically raise the date ceiling created “unneeded uncertainty” that could “potentially lead to worse fiscal outcomes.”

“I can’t believe I need to explain this,” Andrew Lo, a professor of finance at M.I.T.’s Sloan School of Management, responded to the survey. “By risking default, the U.S. is injecting risk into the holdings of both domestic and foreign investors. Such investors will respond to this risk as all rational agents do—by holding less U.S. debt, increasing our borrowing cost.”

And what’s the worst that can happen?

If Congress fails to raise the debt ceiling (or the President vetoes a bill to raise it), the government can’t borrow any more money, and if it can’t borrow to pay its creditors, that would be a default, or at least the beginning of one. At home, the financial markets would plummet, but the damage wouldn’t stop there. Holders of U.S. debt wouldn’t get paid - mutual funds, insurance companies, and ordinary Americans who hold government debt directly or in their retirement accounts. The government would only be able to pay its bills based on revenue coming in the door, so many employees and businesses that provide services to the government would only get paid haphazardly. Tax refunds would be put on hold, and Social Security checks would likely be delayed. How bad the situation gets will depend on how long the crisis lasts.

In the long term, a default would raise the perceived riskiness of U.S. debt, and the government would have to pay more to borrow money. That would increase the portion of the federal budget devoted to simply paying interest on the debt and could raise the cost of other kinds of borrowing, like home mortgages.

Other countries have defaulted on their debt, and while that may have caused problems at home (Greece defaulted in 2015, and Argentina defaulted three times this century), those defaults did not rock the global economy. But U.S. interest rates would shoot up if the debt ceiling isn’t raised and there is no cash available to pay the government’s bills. That matters because U.S. Treasury rates are the basis for most other interest rates around the world, from what other national banks charge, to what businesses and homeowners have to pay to borrow. That’s because the entire global financial system is built on the world’s confidence that the U.S. will always pay its bills.

In fact, rates jumped when the Treasury unexpectedly announced in mid-2023 that it would need to borrow about a third more than it had expected, in order to meet pandemic relief payments and higher interest rates on Treasury notes. That decision sent the yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury bill up a full percentage point, from 3.97% to 4.98%, in a matter of weeks. “People who were going to lend the U.S. government money were getting more and more worried that the U.S. government wouldn’t pay them back, so they commanded a higher interest rate,” said Tilley.

There’s little argument among economists that Congress can and should figure out how to reduce the size of the deficit. But playing chicken with the debt ceiling is not the way to do it.

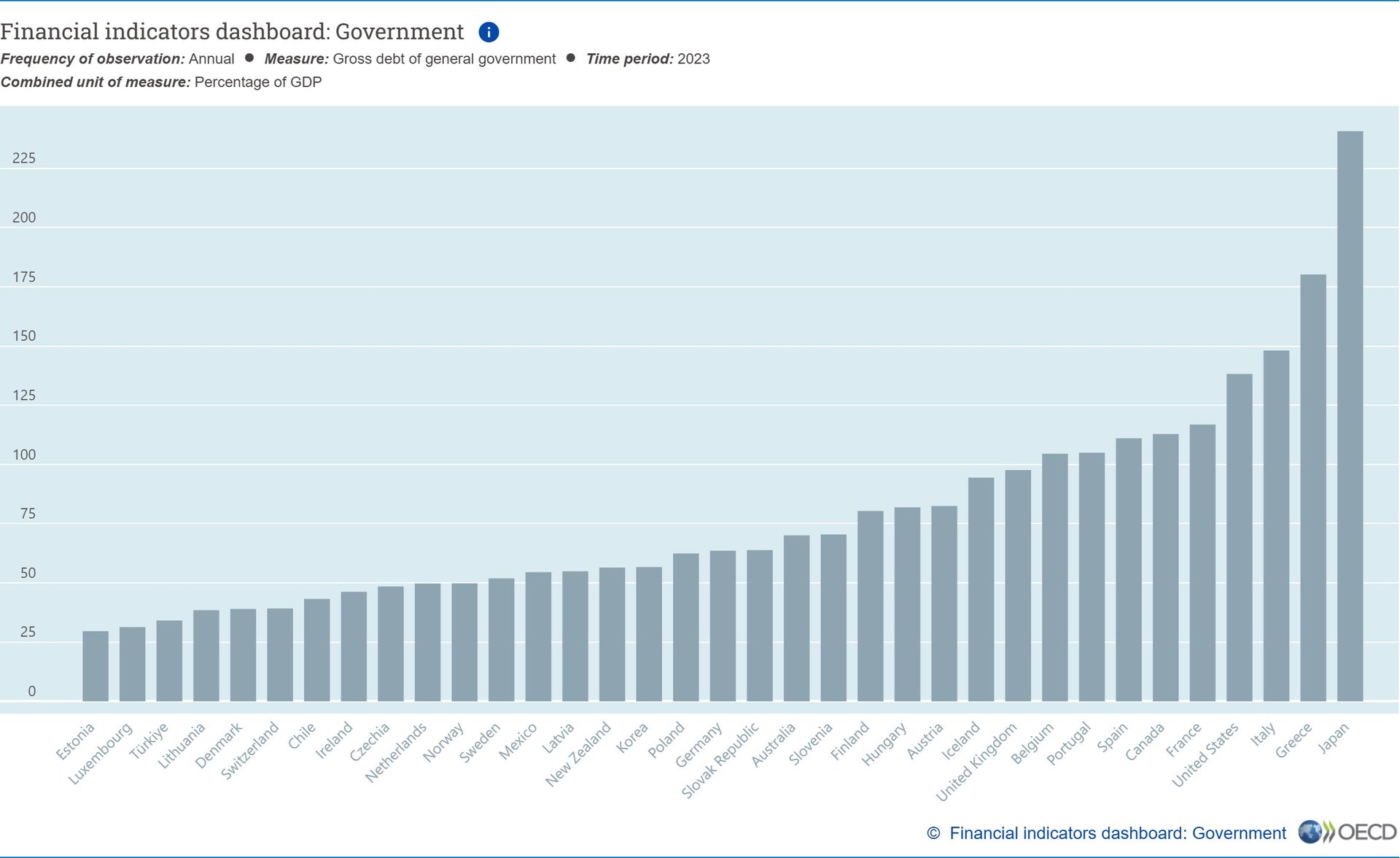

Now, the Federal debt is at about 120% of GDP, that’s up from an average of about 67% over the past several decades, though still below the 132% level it hit in the last year of Trump’s first term, as pandemic relief and a stagnant economy forced the government to borrow a record amount. So how high can the debt go? It’s not about the dollar amount, note economists. Nor is it necessarily about a fixed percentage. Japan’s debt, after all, is at 241% of GDP.

The debt does not need to return to zero. Unlike households, the government can borrow relatively indefinitely. So while there’s no fixed number for how much a country can borrow relative to its economic productivity, and therefore no fixed limit to the ceiling, the key, says Jeffrey Campbell, a professor of economics at the University of Notre Dame, is credibility.

“Debt becomes unsustainable—for a company or for a country—when investors stop believing that they will be repaid,” Campbell said in an email. “The money at hand now is not relevant for that. What is relevant is investors’ beliefs about money at hand at the time of repayment.” And the key to that, he said, is the difference in growth between spending and taxes. “If spending grows much faster than tax revenues, then the government will have a problem servicing its debts without running a Ponzi scheme.”

So why bother with the debt ceiling?

The debt ceiling is governed by a law that goes back to 1917, when it was put in place to help the government finance the U.S. role in World War One. With various revisions, it’s now seen as a way to prevent runaway spending. The idea is to make Congress think twice before it orders the government to spend money. In other words, if taxes don’t cover spending, Congress has to make sure it wants the government to borrow enough to cover the difference. But that hasn’t really worked, says Alex Morris, CEO of F/m Investments, an investment management advisory firm based in Washington. “Many argue it [has] failed,” Morris wrote in an emailed comment. “Spending continues, and [the ceiling] has become a political hot potato, oscillating between fiasco, farce, and frustrating policy failure.”

Pavlo Buryi, associate professor of economics at Harrisburg University in Pennsylvania, compares the U.S. budget process to an electrical circuit that risks being overloaded as more appliances are plugged in. “Without periodic upgrades—or, in this case, an increased ceiling—the system risks a critical failure,” he said.

In fact, since 1960, Congress has moved 78 times to permanently raise, temporarily extend, or revise the definition of the debt limit—49 times under Republican presidents and 29 times under Democratic presidents, according to the Treasury.

But the main question remains unresolved: Is there an actual limit to the ceiling? As Buryi notes, economists and policymakers are divided. One side warns of a tipping point, where the debt-to-GDP ratio becomes unsustainable when debt levels exceed a country’s ability to generate the growth or revenue needed to service that debt, and for smaller economies, that’s usually around the 100% level, while the other side argues that as long as the world has faith that the U.S. economy will grow fast enough to repay its debt, it can keep borrowing.

In the meantime, as Mike Englund, chief economist at Action Economics, an advisor on fixed income and foreign exchange, the debt ceiling “showdowns” produce sizeable distortions to the economy but rarely result in actual spending cuts.

“It is effectively a scheduled publicity stunt that legislators either like or hate,” said Englund, “depending on whether they like the publicity.”