The truth about Donald Trump's tax and tariff plans

Tariffs can't actually replace income and corporate taxes, and more to know about how Trump's plans would effect the economy

A version of this article originally appeared in Quartz’s members-only Weekend Brief newsletter. Quartz members get access to exclusive newsletters and more. Sign up here.

With Election Day just around the corner, it’s a good time to look at some of the implications of Donald Trump’s proposed tax plans, and how they’d help — or hinder — the U.S. economy.

The way Trump sees it, paying taxes is dumb. When Hilary Clinton noted in a 2016 debate that Trump hadn’t paid taxes, his response was, “That makes me smart.” So when a Bronx barber asked him last month if he could eliminate income taxes, Trump had a ready answer: “There is a way, if what I’m planning comes out.” A few days later, podcaster Joe Rogan asked Trump if he was serious about replacing federal income taxes with tariffs on imported goods. “Yeah, sure, why not?” Trump replied.

It’s not clear if Trump was referring to corporate or personal income taxes, but eliminating either — or both — could effectively end Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, and any military spending. The tariffs that Trump has said would replace taxes would likely collect only about 2% of the federal budget.

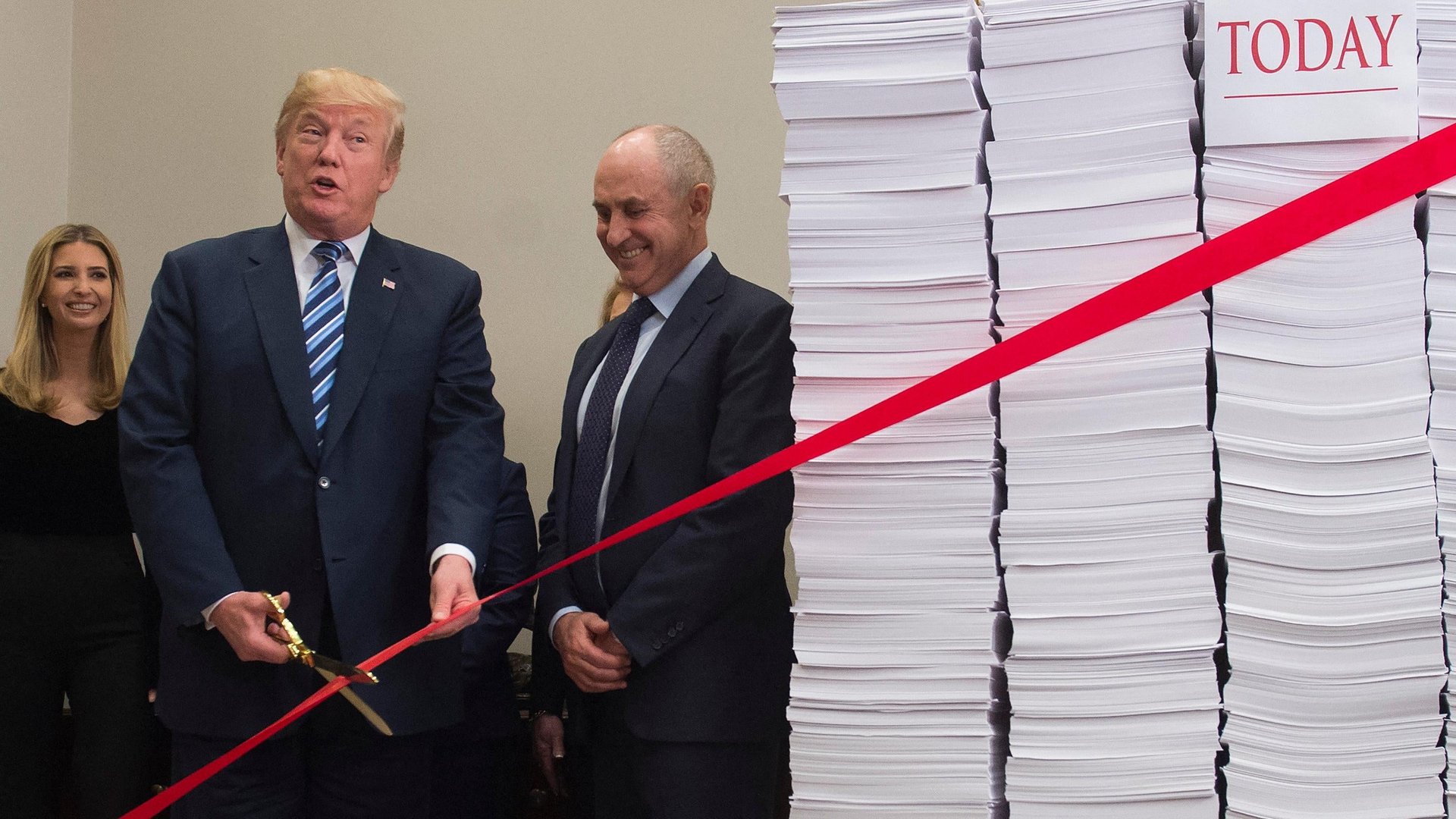

Trump has promised a fiscal and regulatory revolution the day he takes office, but his tax and tariff plans have many economists and business people scared.

A group of 23 Nobel Prize-winning economists said in an open letter last week that Trump’s tax policies would be bad for America. “His policies, including high tariffs even on goods from our friends and allies and regressive tax cuts for corporations and individuals, will lead to higher prices, larger deficits, and greater inequality,” they wrote.

Tariffs can’t replace taxes

But hold on, because some economists say radical change may not be in the offing. To enact most of his policies, Trump would need a reliable majority in both chambers of Congress — which seems unlikely at the moment.

“A president can’t snap his fingers and change the economy,” said Kristen Monroe, a political economist and professor of political science at the University of California Irvine. “They keep talking about the economy, and neither Biden nor Trump is directly responsible for the economy. Like with so many other things, Trump is overly simplistic.”

Monroe noted that battling inflation, which is pretty much back to normal now, has been the work of Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, a Trump appointee.

Trump’s own aversion to taxes is legendary. As The New York Times reported in 2020, he paid $750 in federal income taxes the year he won the presidency. In his first year in the White House, he paid another $750. And he paid no income taxes at all in 10 of the previous 15 years, largely because, as The Times noted, “he reported losing much more money than he made.”

For inspiration, Trump has turned to the U.S. at the end of the 19th century, when most economies existed within national boundaries and supply chains stretched a few hundred miles by rail — not thousands of miles by sea and air.

“When we were a smart country, in the 1890s… this is when the country was relatively the richest it ever was. It had all tariffs. It didn’t have an income tax,” Trump said after the barber’s prodding. “Now we have income taxes, and we have people that are dying. They’re paying tax, and they don’t have the money to pay the tax.” It’s not really clear who he (wrongly) thinks is dying and how that’s related to income taxes. Some 40.1% of American households, most of them in the lowest income brackets, pay no federal income tax at all.

“Can tariffs replace the income tax?” asked the Peterson Institute of International Economics, a generally conservative group. “Simply put, no,” was its own answer. Tariffs are levied on imported goods, which totaled $3.1 trillion in 2023. The income tax is levied on incomes, which exceed $20 trillion. The Treasury raises about $2 trillion in individual and corporate income taxes, and as the Peterson folks said, “It is literally impossible for tariffs to fully replace income taxes.”

And it gets worse. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget noted recently that while Democratic nominee Kamala Harris’ economic plans would add about $3.95 trillion to the national debt by 2035, Trump’s plan, by reducing taxes but not cutting spending to match, would add a whopping $7.75 trillion.

The old Trump tax cuts

One likely scenario, economists and political observers say, is that Congress, in typical dilatory style, simply does the least it possibly can, and just extends Trump’s 2017 cuts. That’s when Congress enacted the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, a $1.9 trillion tax bill favoring corporations and the wealthy. It slashed the corporate tax rate from 28% to 21%, cut exemptions for local and state taxes, and cut the charitable donation deduction. It also doubled the exemptions for inheritance and generation-skipping transfer taxes, which were already at $5 million, far above the need of the vast majority of Americans.

“Corporations are literally going wild over this,” Trump said when signing the bill.

But it didn’t do much to stimulate the economy or boost employment.

“Corporations, not workers, are the big winners,” the liberal Center for American Progress noted in a lengthy analysis. “The massive corporate tax cut is costing more than expected and not trickling down to workers.”

Now Trump is talking about cutting the corporate tax rate to 15% if he wins. That will be great for corporate bottom lines, at least in the short run. And like the 2017 tax cuts, it will likely prompt a wave of stock buybacks that benefit the already wealthy as corporate executives and large shareholders seek to grab some of the cash that will accumulate in corporate coffers.

The new Trump tax cuts

Don’t expect any new tax cuts to actually stimulate the economy. Greg Daco, chief economist at the consulting firm Ernst & Young, noted in an interview that tax cuts rarely pay for themselves. “That’s the dirty little secret,” Daco said. “The notion that if you cut taxes the revenue is going to be offset by stronger economic activity is not a reality.”

That, he said, is because the so-called “implicit effect,” the multiplier of economic activity, is generally quite low. For corporations, the multiplier is about 30 to 40 cents on the dollar, Daco said.

“If you cut taxes by a dollar you get 30 to 40 cents of additional economic activity,” he said. That may sound great, but as Daco added, “from a government perspective, you’ve lost a dollar in tax revenue and you’ve generated 30 cents of additional activity which will be taxed at 15%, or 4 1/2 cents. So you’ve lost 95 1/2 cents of revenue,” which could be used to pay for Social Security, Medicare, the military or even to pay down the national debt.

And if the existing tax cuts are extended past their 2025 expiration date, that’s not going to be good for the economy.

“If you extend the tax cuts, you get less revenue and have an increase in the debt,” Daco said. “We are running deficits of around 6% of GDP in good times. This is a concern from a fiscal standpoint and it does lead to higher interest payments on debt.”

The Trump tariffs

We’ve looked at them before, and they are still a generally bad idea. A recent Peterson Institute study found that the tariffs would cost an average household at least $2,600 a year, and a study from Yale University’s Budget Lab found that the cost could be as high as $7,600. That’s nothing for Elon Musk or John Paulsen, two of Trump’s billionaire supporters. But for lower-income Americans, much of whose income is spent on imported goods like shirts and shoes made in China, that’s effectively a huge tax increase.

For companies that depend on imported parts or raw materials, a hike in prices and a lack of substitutes could put them out of business. A second Trump administration would basically recreate some of the effects of the pandemic’s supply chain breakdowns, but with tariffs 10 times or more higher than the first time around.

“Trump’s proposed tariffs on China ignore the realities and needs of our small businesses,” said Javier Palomarez, CEO of the United States Hispanic Business Council. “Such tariffs would increase prices for consumers, raise the cost of production for businesses, reduce sales, and decrease the employment rate.”

Basic capitalism says foreign firms won’t absorb the cost of tariffs, they’ll simply jack up prices to cover the cost of the tariffs — setting a new threshold for U.S. manufacturers, who will set their prices just as high to make as much profit as they can.

“Cutting tariffs would counter the punishing increase of the cost of living that American families are experiencing,” the U.S. Chamber of Commerce wrote in 2022, referring to Trump-era tariffs left in place by President Joe Biden. “It would also enhance the competitiveness of U.S. manufacturers, and address the unfairness of the tariff code, which hits the poor hardest.”

Tariffs are effectively a regressive sales tax, and the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimated that they cost the average American household more than $1,200 in 2020 alone. Contrary to popular misconception, the New York Fed wrote recently, the Trump-era tariffs, with a small add-on from Biden, “continue to be almost entirely borne by U.S. firms and consumers.”

A better way to cut the deficit would be to raise taxes on the wealthy and end the cap on Social Security and Medicare taxes, which would likely raise enough money to fully fund those programs in perpetuity. “If you didn’t have a cap on what you pay for Social Security,” Monroe said, “then everything in the system would be solvent.”