COP27: The $100 billion question

Plus: Egypt's human rights record isn't on the agenda

Hello COP27 delegates and readers,

The principle of “common but differentiated responsibility” demands that rich countries, responsible for the majority of historical greenhouse gas emissions, cover some of the bill for poorer countries to adopt carbon-cutting plans and compensate for climate damages.

Beginning Nov. 7, that dynamic is sure to be the crux of tensions during COP27 over two weeks in the Egyptian Red Sea resort town Sharm El-Sheikh. Egyptian officials have promised to force the issue by making this COP all about the money.

For years, the question of climate finance has been kicked down the road, leaving the overall sum—wealthy countries committed more than a decade ago to raise at least $100 billion annually by 2020—far short of what it should be.

This year, the Egyptians promise, negotiations will focus as much on how to distribute committed climate finance as raising more commitments. “It’s not about how much should be in the piggy bank, but about whether there even is a piggy bank,” says David Waskow, director of the international climate initiative at the World Resources Institute.

So it may be time to shake up the old alliances. In nearly 30 years, only one country, Turkey, has officially shifted from “developing” to “developed.” Several countries that now have robust industrial economies and large carbon footprints—South Korea, South Africa, Israel, India, not to mention China and Middle East fossil fuel exporters like Saudi Arabia and Qatar—still count as “developing” in the world of climate diplomacy. And some “developed” countries like the UK, Germany, and Japan that have dedicated substantial sums to climate finance still get unfairly lumped in with rich laggards like the US, Canada, and Australia, says Sarah Colenbrander, climate director at ODI, a UK think tank.

The rich-poor narrative lets emerging emitters off the hook and creates a finger-pointing, polarized atmosphere that disincentivizes creative, collaborative diplomacy, Colenbrander says. “Successes in climate negotiations in recent years have not come from that dynamic,” she says. “Successes have come from alliances between rich and poor, from the recognition that within both categories there are progressive and not-progressive countries.”

No matter how you tabulate responsibility, the question for all countries is the same, she says: “At what point do you stop stamping your foot, and choose to be a part of the solution?”

What to watch for

🗓️ Agenda fight. Delegates will vote by Sunday on the negotiation agenda, which requires unanimous approval. The US has indicated it is open to including loss and damage on the agenda, which would be a first in COP history and raise the odds that some kind of deal or plan for it will emerge.

🧑💼 World leaders pontificating. The summit’s first few days traditionally feature a litany of speeches from presidents and prime ministers, but this year there will be some notable absences, including India’s Narendra Modi, China’s Xi Jinping, and Canada’s Justin Trudeau. After some waffling, the UK’s Rishi Sunak will attend, as will US president Joe Biden (but not until Nov. 11).

🏨 Conference chaos. More than 30,000 people are registered to attend COP, making it one of the biggest events ever hosted in Sharm El-Sheikh. Last-minute work on facilities is ongoing, and there are sure to be long lines, confusion, and in a police-heavy country like Egypt, lots of security. At least one foreign activist has already been arrested (and released).

Climate finance by the numbers

$100 billion: Target for annual climate finance to be reached by 2020, as agreed in 2009 climate talks.

$21 billion-$83.3 billion: Annual climate finance raised by 2020, depending on whether loans and private-sector finance are included in the tally, or only grants.

$4.3 trillion: Actual climate finance needs stipulated by developing countries in their most recent climate strategy documents.

20%: Share of global GDP that has already been wiped out by climate impacts (also known as “loss and damage”) in 55 of the most vulnerable countries, equal to about $525 billion.

$16.8 million: Donations made by rich countries explicitly to cover loss and damage costs.

$693 billion: Financial support for fossil fuel companies provided by G20 countries in 2021.

$58.4 billion: Combined profits of five of the largest publicly traded oil and gas companies during the third quarter of 2022 (Exxon, Chevron, Shell, BP, and Total).

Quotable

“There are, over the whole year, multiple opportunities to raise whatever issues with Egypt or other countries, related to civil liberties, human rights, and other related issues... I hope that for two weeks the focus will be on the people dying around the world.”

Another major issue hanging over the summit will be Egypt’s subpar human rights record, which has come under fire from watchdog groups, European politicians, and climate activists in recent weeks. The country has thousands of political prisoners and oppressive laws for civil society groups. One prisoner, British-Egyptian dissident Alaa Abdel Fattah, has drawn particular attention after a prolonged hunger strike and is planning to stop drinking water if he is not released before COP27.

One big number

4.4 trillion cubic meters per year: That’s how much natural gas the world will consume annually by 2030—and plateau at that level for the following two decades, according to a major recent report from the International Energy Agency. It’s the first time the IEA has projected anything other than everlasting growth for that fossil fuel, and a major vote of confidence for the future of renewables ahead of a COP that is occurring in the midst of a global energy crisis.

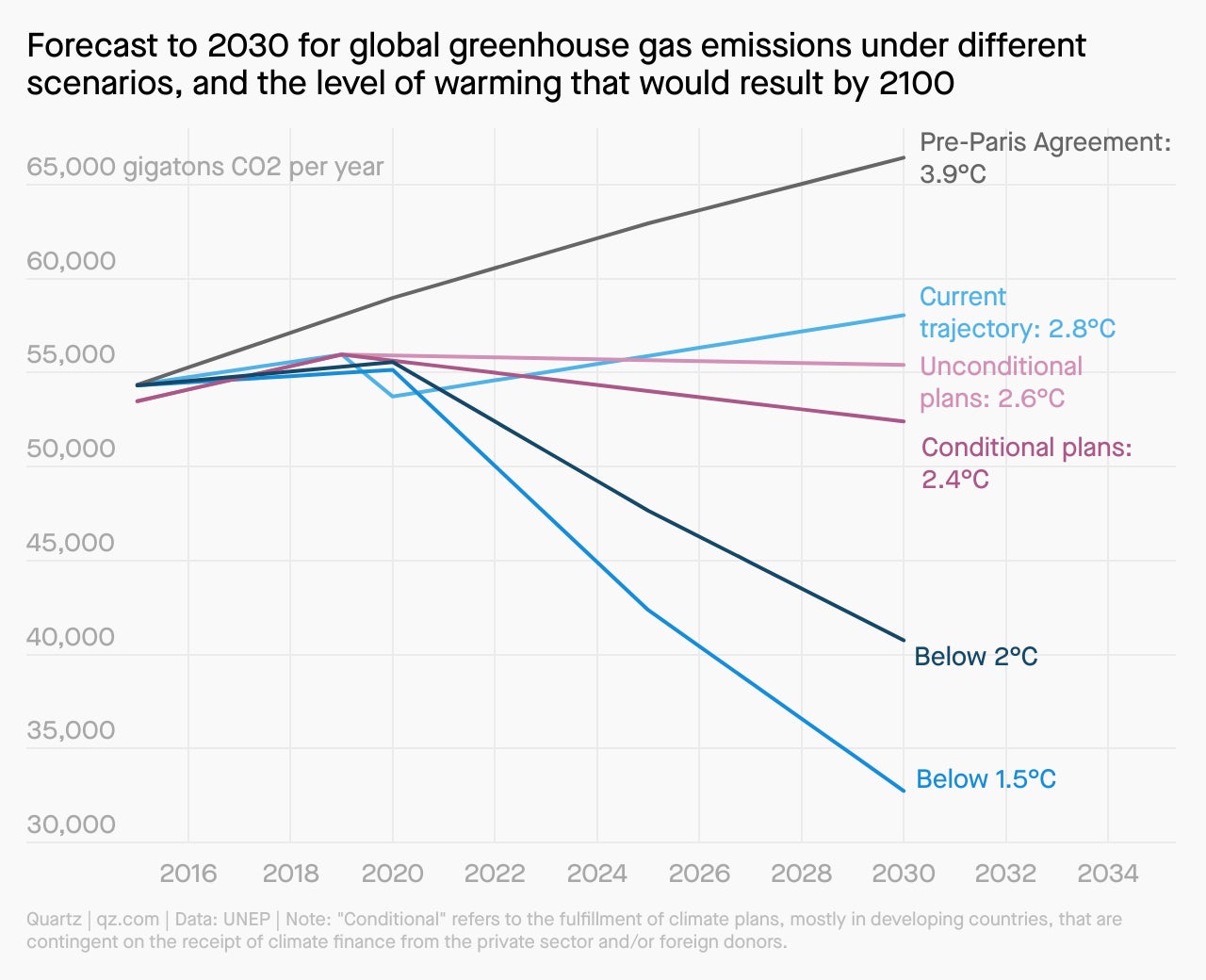

The future of emissions and global temperatures

Global climate plans announced by countries to date have bent the “emissions curve” significantly from where it was prior to the 2015 Paris Agreement, but far from enough to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

Thanks for reading! Stay tuned—we’ll be back in a few days from the ground in Sharm El-Sheikh as COP27 opens.

— Tim McDonnell, climate and energy reporter; Michael J. Coren, deputy editor of climate and emerging industries; Amanda Shendruk, visual journalist; and Morgan Haefner, deputy email editor.