COP27: The good, the bad, and the vaguely

Plus: What to expect for COP28 (and humanity)

Hello COP27 delegates and readers,

In its final hours, COP27 looked like it might fall apart without a deal. Diplomats were divided along the oldest battle lines in climate diplomacy: rich versus poor countries. This time, the dispute was whether to redraw those lines, increasing the number of nations that would help poor ones weather rising temperatures.

In the end, after an all-night negotiation into the dawn hours of Nov. 20, nearly every country on Earth agreed to help defray the cost of climate impacts and natural disasters on poor countries. The creation of the dedicated “loss and damage” fund, sometimes called climate reparations, has been a long-sought goal of climate activists. But COP27 failed to deliver on another coveted objective seen as crucial to limiting temperatures: phasing down global production and consumption of fossil fuels.

The good: Loss and damage gets a dedicated fund

The deal for the new fund still lacks details and financing. If previous climate finance goals are any guide, there will be a long and excruciating road ahead before a loss and damage fund pays out compensation.

The bare-bones guidelines laid out for the fund so far indicate the pool of contributors will expand beyond the US, EU, and traditional donors to include developing countries, development banks, and the private sector. This broadening of responsibility, a precondition for EU negotiators in particular, will likely guide climate fundraising deliberations in the years ahead.

But the deal’s language, while vague, was interpreted by some civil society groups as narrowing the pool of beneficiaries, potentially excluding relatively higher-income developing countries such as Pakistan. Yet the EU’s top negotiator specifically mentioned Pakistan as a likely recipient in his closing speech at COP27. More details of the fund, including how much money it aims to raise, will be negotiated in advance of next year’s COP28 summit in the UAE.

The bad: No sunset for oil and gas

In response to pushback from Saudi Arabia and other major oil and gas exporters, phasing down the use of those fossil fuels was axed from the agreement. Instead, it calls only for a wind-down of “unabated coal,” essentially copying the language of last year’s agreement in Glasgow.

For a COP billing itself as all about “implementation” of climate plans, this outcome disappointed, to say the least. The move to phase down all fossil fuels is at the core of any science-based implementation plan.

In the end, the progress needle stayed dismayingly still. As Nat Keohane, president of US think tank the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions put it, “There was a lot of running back and forth furiously to stay in the same place.”

What to watch for

💸Will countries force financial institutions to get in line? An oft-overlooked clause of the Paris Agreement calls on signatories to make all “finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development”—in other words, to push banks, asset managers, and other financial institutions to do their part, something those firms have as yet been unwilling to do. If voluntary commitments can’t do the trick, more regulation will be needed, said Julie Segal, senior manager for climate finance at the Canadian advocacy group Environmental Defence: “We need firm lines to keep the financial system from going awry of the public interest.”

🇨🇳How will China tackle methane? China’s top climate diplomat Xie Zhenhua crashed a panel discussion on methane emissions on Nov. 18 to announce that his country, the world’s top methane emitter, is cooking up a national strategy for curbing methane emissions, something it had previously declined to do. Methane is a more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, and seen as low-hanging fruit to make a serious dent in warming in the near-term.

🇦🇪What will COP28 achieve when it’s hosted by a major oil and gas exporter? Next year’s COP28 will be hosted in Dubai, the commercial capital of the United Arab Emirates, and given that country’s economic forte, will likely be the most fossil fuel-powered climate summit to date. The UAE pavilion at COP27 was a sprawling, whitewashed affair with plenty of high-tech, interactive display screens showing off the country’s global energy investments and sustainable urban design accomplishments—and, perhaps indicating the vibe at COP28, a forecast of UAE’s 2050 energy mix, featuring 12% “clean coal” and 38% natural gas.

⛓️Will Egypt release Alaa Abd El-Fattah? While world leaders pontificated during the first week of COP27, Egypt’s best-known political prisoner nearly died from a food and water strike, according to a harrowing account released by his family after their first visit with him in nearly a month on Nov. 17. The attention drawn to his case during COP did not produce a tangible result, with no indication of a change in Egypt’s stance or any sign that UK prime minister Rishi Sunak—Abd El-Fattah is a UK citizen—was able to achieve anything on his behalf. “He will have no choice but to resume his hunger strike imminently if there continues to be no real movement on his case,” his family wrote.

COP27 by the digits

- $234 million: Pledges made by high-income countries to the UN Adaptation Fund during COP27

- $394 million: Pledges made by high-income countries for loss and damage during COP27

- 30%: Portion of tropical forest in Africa that is included in leasing blocks for oil and gas drilling

- 70%: Amount that global coal demand will fall between now and 2050, based on existing government pledges. To limit warming to 1.5°C, it needs to fall 90% in that time.

- 2.7°C: Projected global warming by 2100 based on countries’ current climate plans

- 150: Governments that have signed a pledge that aims to cut methane emissions 30% by 2030

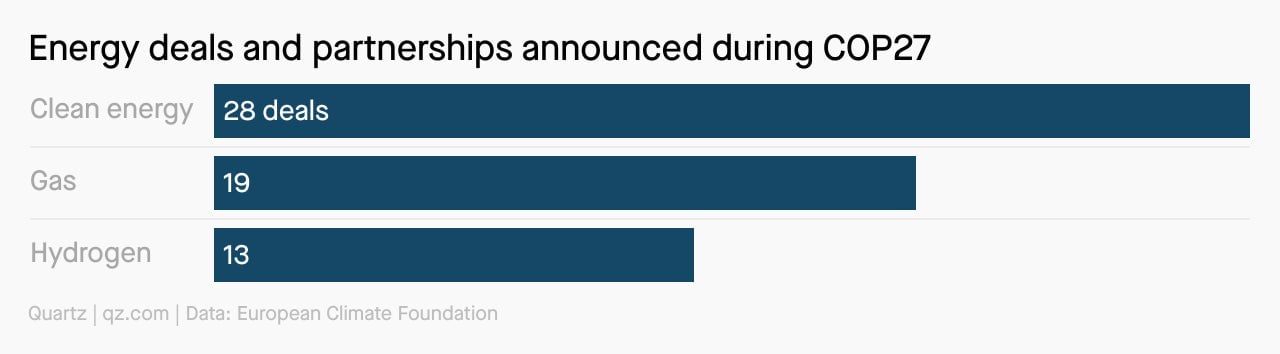

Charting new energy deals

As much as COP is a venue for diplomatic negotiations, it’s also a trade show for the private sector. During COP27, dozens of new energy deals and partnerships were announced, including everything from a plan between oil major BP and the government of Mauritania to explore large-scale production of hydrogen there, to a commitment by a Saudi developer to build a 10-gigawatt wind farm in Egypt. Clean energy deals outnumber natural gas, but the highest-dollar deal (of those that disclosed a value) was a $40 billion agreement between Tanzania, Equinor, and Shell to build LNG export terminals.

🚨Greenwashing alert: sketchy carbon markets

Ever since the 2015 Paris Agreement, diplomats have been hammering out the details of a new UN-backed carbon trading market, through which companies and countries could purchase offset credits derived from forest conservation, solar energy, and other carbon-cutting projects around the world. The writing of those rules inched forward during COP27, but in a way that watchdogs say leaves the door wide open for corporate greenwashing. In short, the market allows some credits to be counted against the carbon footprint of both the country in which they originate, and the buyer—fostering the illusion that global emissions are falling faster than they really are. The rules also allow countries to keep some details of their carbon credit offerings secret, and establish a UN review committee that lacks any power to correct or punish bad behavior.

Quotable

There was very little opportunity for observers and NGOs to have meaningful contributions to the negotiations. But, the majority of civil society in Egypt have gained a lot from this COP. Whatever your agenda, whatever you’re fighting for, having the spotlight, and the open-mindedness of many ministers to have critical discussions and take critical feedback, this was not the case before COP… you don’t get this in Egypt.

—Mohamed Kamal, co-managing director of Cairo-based environmental advocacy group Greenish

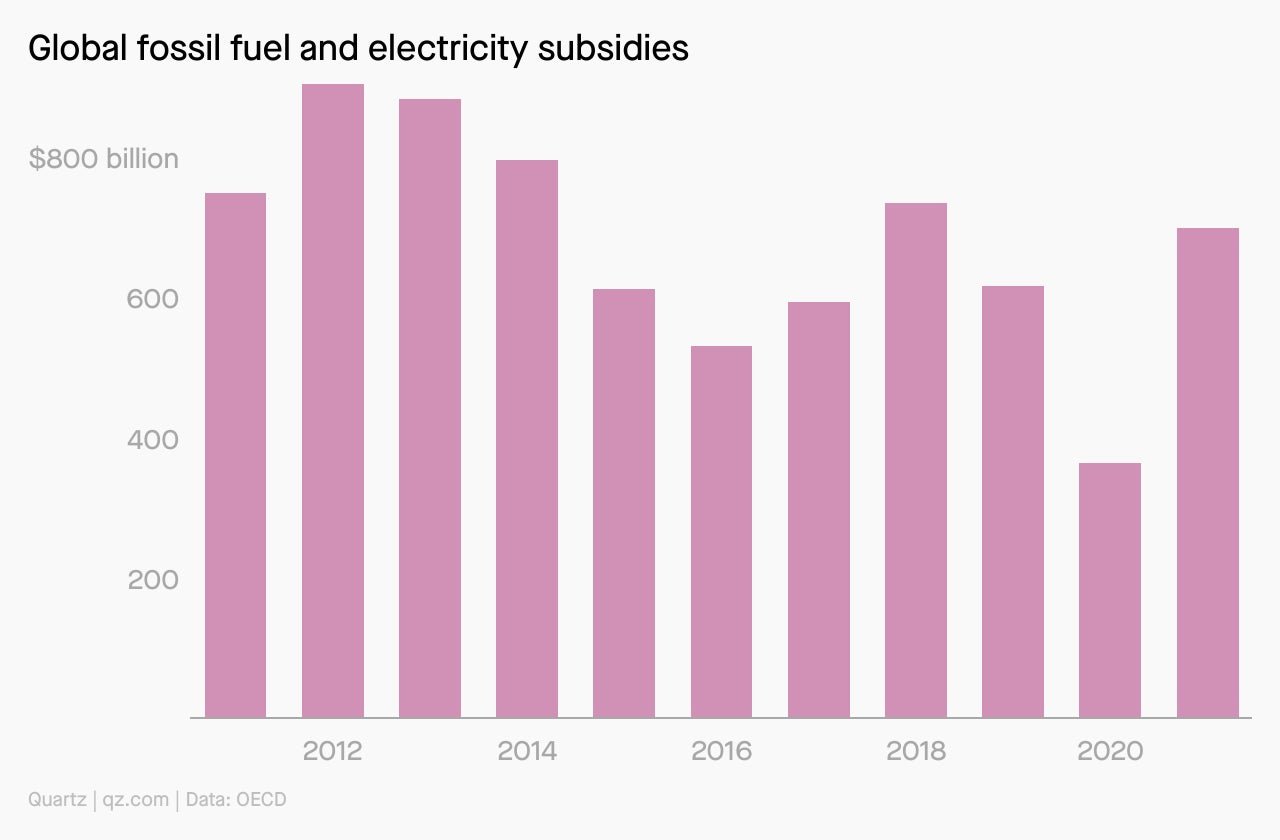

Fossil fuel subsidies are holding back clean energy

An energy crisis in Europe and record high prices for natural gas and electricity should be a time for renewables to shine, right?

Well, government subsidies for fossil fuels are throwing a wrench in that dynamic by shielding consumers from their real cost. Just last year, global fossil fuel subsidies nearly doubled from 2020, and so far this year, the amount of government support is on track to double 2021’s figures.

Pop quiz: NDC shaming the G20

NDCs, or nationally determined contributions, are the emission reduction goals adopted by individual nations in 2015, and were meant to be updated in 2020. Last year, participants at COP26 decided that updated NDCs were not ambitious enough, and decided to give themselves another year to revisit their targets. Many countries, however, have still not submitted new goals.

How many G20 countries have updated their NDCs for 2022?

- Exactly half

- Lucky number 7

- An even dozen

Answer: Sadly, only 7 of the G20 countries have updated their NDCs: Australia, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Turkey, and the UK. At the moment, only Australia has set a stronger target, while the others did not increase their ambition, or an analysis of their NDC by Carbon Action Tracker is still pending.