Coronavirus: Poop there it is

Hello Quartz readers,

Hello Quartz readers,

So far, Covid-19 testing has failed miserably to track the progress of the pandemic in the United States. But scientists are hoping that a simple fact of life will complement swab testing: Everybody poops.

In cities across the US, scientists are working with public health officials to conduct wastewater-based epidemiology. Research early in the pandemic showed that people infected with SARS-CoV-2 shed bits of the virus’ genetic material in their feces. So by measuring the viral load in sewage, public health officials can get an idea of how prevalent the coronavirus is within a community.

In small enough settings, wastewater monitoring could even predict outbreaks. Already, it has been used to catch outbreaks among students at the University of Arizona and Utah State University before they displayed symptoms.

“Wastewater is convenient in that you get a population level understanding of transmission in a single sample,” says David Larsen, an environmental epidemiologist at Syracuse University who’s been working with his local health department in Syracuse, New York to monitor wastewater. “It’s extremely cost effective.”

Okay, let’s get started.

A grief history

As India crosses 4.2 million Covid-19 cases, there are lessons its government can learn from the Spanish flu pandemic more than a century ago.

Under the rule of the British Empire, India lost more than 10 million lives to the 1918 pandemic. The year was made more excruciating by meager rainfall, which crippled agriculture and led to famine in major parts of the country. Yet, there were districts that performed significantly better than others.

During the pandemic, districts under Indian officers saw up to 15% fewer deaths than those under the control of British officers, according to a paper (pdf) by Guo Xu, assistant professor of business and public policy at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley.

What happened? Xu pointed to a lack of local knowledge on the part of British DOs. “Most British… recruits never saw India prior to their first deployment,” he wrote. “Many had limited command of the local languages.”

Another element was the districts’ amount of relief aid. While there was no difference in spending between Indian and British DOs before November 1918—when the second and strongest wave of the pandemic hit—Indian DOs increased their spending during the second wave by twice as much as the British officers did.

In political economics, Xu wrote, there are two main schools of thought. One, first promulgated by German sociologist Mark Weber, says that a bureaucracy should be “dehumanized.” Which is to say, that it should be a “rational” organization led by unbiased processes.

The second, more recent view argues for greater representation in public organizations from the people they wish to serve. “Greater representation, it is argued, helps align preferences, provide social incentives, and enable bureaucrats to leverage private information,” Xu wrote.

In India today, this loosely translates into the federalism of the states, where the central government plays a nodal role, but allows for greater autonomy at local district levels. As the pandemic takes its toll, this autonomy would ideally extend beyond the political sphere into the financial. The one thing that emerges most strongly from Xu’s work is how bureaucratic representation can make a state more responsive during a crisis.

It’s the climb

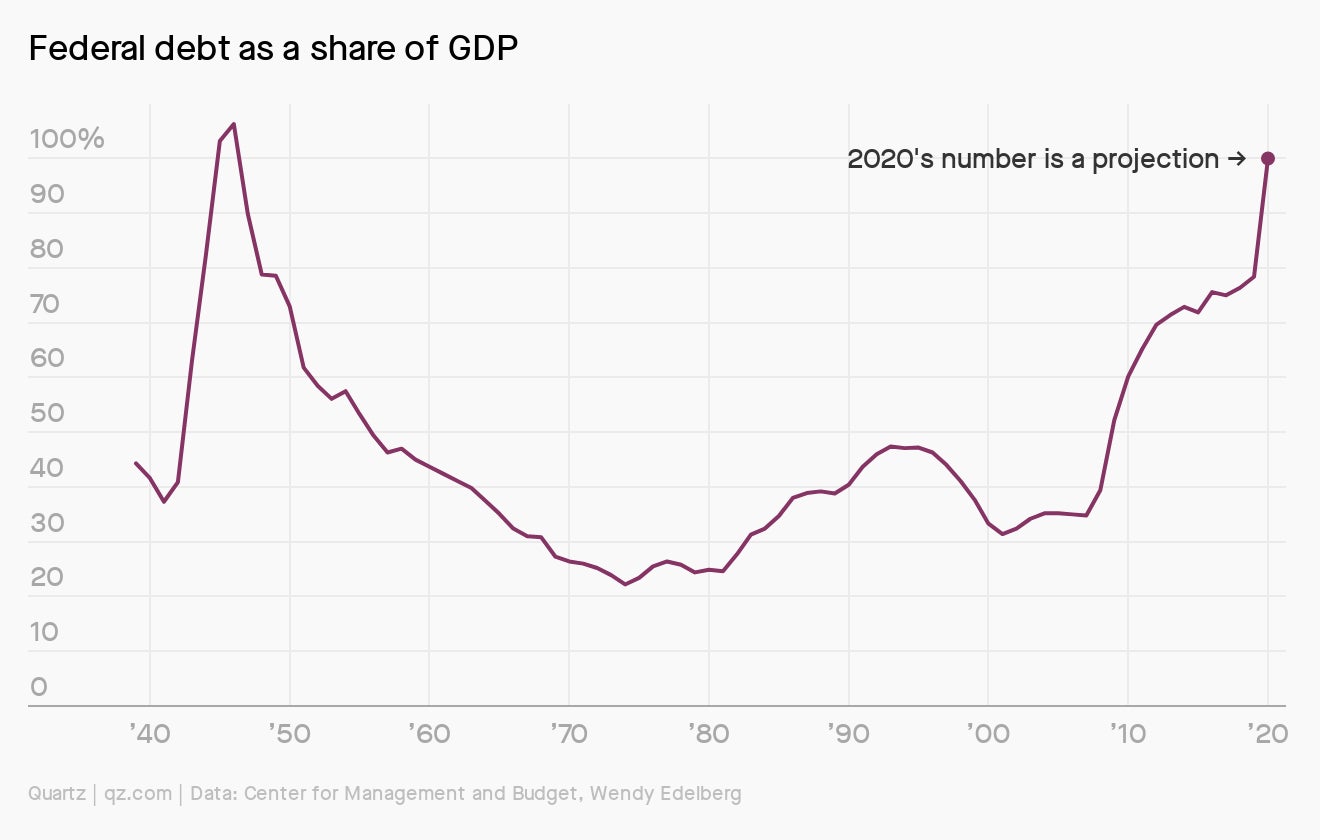

The US is heading for levels of debt unseen since World War II. Government debt as a ratio of GDP is poised to exceed 100% for the full fiscal year, making it the first time that’s happened since 1946, according to projections from the Congressional Budget Office.

Still, quite a few experts would like to see the US borrow even more. Congress has already spent nearly $3 trillion to support businesses and workers, and Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell believes it’s too early for politicians to be stingy. “Additional fiscal support could be costly, but worth it if it helps avoid long-term economic damage and leaves us with a stronger recovery,” he said in May.

This is one of three charts that finance reporter John Detrixhe and data editor Dan Kopf use to show how the US economy is going Xtreme (and not in a fun Mountain Dew way).

Parental controls

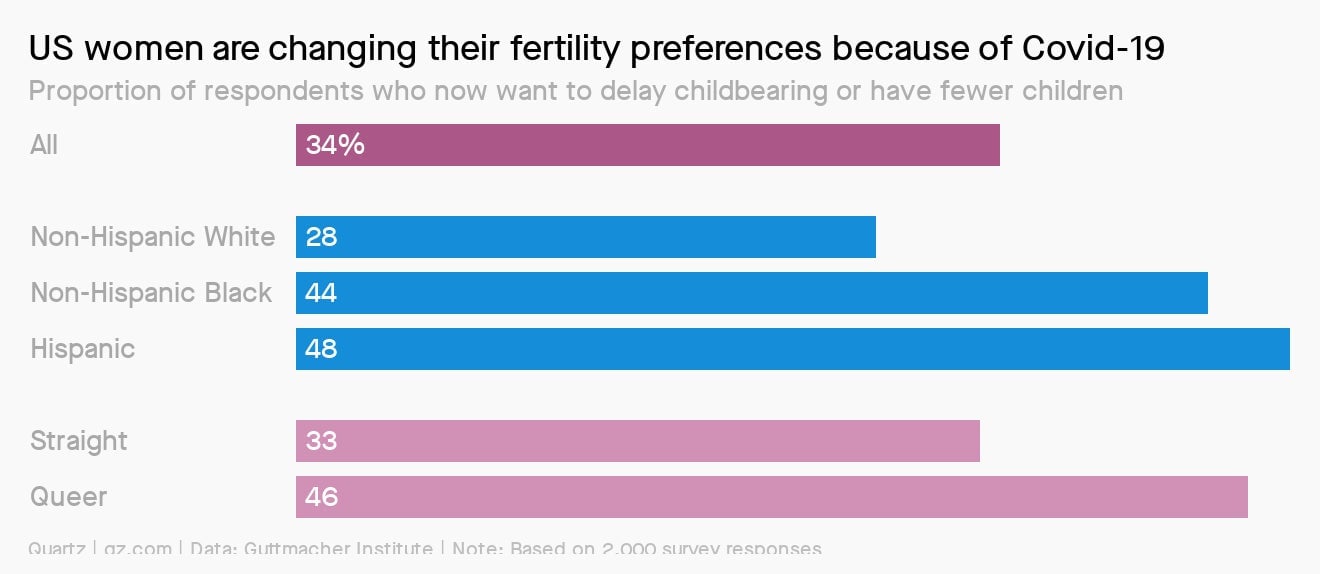

About one third of US women have decided to have fewer children or delay pregnancy because of coronavirus, according to a survey from the Guttmacher Institute. The change of plans is significantly more common among minority groups and those who are economically vulnerable.

The shift follows a pattern in US history: During times of economic stress, the birth rate drops. Amid so much economic difficulty and life uncertainty, it’s estimated the number of new US births could fall by half a million next year.

But not everyone has responded to the pandemic by putting off family plans: The Guttmacher survey found 17% of US women wanted to have more children or have a child sooner.

You asked

Many of us think that being outdoors, especially with a light breeze, is a safer environment to be with other people, with a six-foot spacing but without masks. Is this safe?

When we think about Covid-19 transmission, what we’re really thinking about is tiny droplets that can contain the virus and potentially be inhaled. Research dating back to the 1800s first suggested that “larger” droplets (five microns in diameter or more) can travel a maximum of two meters, or about six feet. Pandemics and other more recent infectious diseases back this theory up. The tricky question has to do with small droplets (smaller than five microns), which are also known as aerosols. These droplets can evaporate and travel even farther than six feet—maybe up to 27 feet!

Outside, particles at any size are quickly dispersed and diluted, as a recent article in the scientific journal the BMJ points out. This means that theoretically, yes, being outside with a light breeze is less risky than being indoors, but the risk still isn’t zero. We’re emitting large and small droplets as we talk and breathe all the time, and breathing heavily from physical activity may propel these droplets further.

A preprint of a paper from researchers based in Japan suggests that being outside is 18.7 times less risky than being indoors, but as with so many other topics we’ve covered here, no one knows exactly what that risk is right now.

Essential reading

- The latest 🌏 figures: 27.4 million confirmed cases; 18.4 million classified as “recovered.”

- Case studied: How India’s engineering schools are keeping calm and carrying on.

- Capture the red flag: Auditors are struggling with remote work.

- Spin cycle: Cheap Chinese exercise bikes are beating US tariffs.

- Blocking it out: Legos are proving to be the perfect pandemic toy.

Our best wishes for a healthy day. Get in touch with us at [email protected], and live your best Quartz life by downloading our app and becoming a member. Today’s newsletter was brought to you by Katherine Ellen Foley, Manavi Kapur, Dan Kopf, John Detrixhe, Katie Palmer, Olivia Goldhill, and Kira Bindrim.