Future of Finance: Why Chinese companies like to raise money in New York

It’s time for the Future of Finance dispatch to take inventory. You have a gazillion newsletters to choose from and we want to make sure you’re getting the information you need. Is there anything you’ve loved? Anything you’ve hated?

It’s time for the Future of Finance dispatch to take inventory. You have a gazillion newsletters to choose from and we want to make sure you’re getting the information you need. Is there anything you’ve loved? Anything you’ve hated?

Let us know! We’ll be sharpening our pencils, running an audit, and taking a breather from these missives for the next few weeks. You can still sign up here so you’re ready for the next stage of our work. In the meantime, keep up with Quartz’s finance and economics coverage here and here.

Hello Quartz readers!

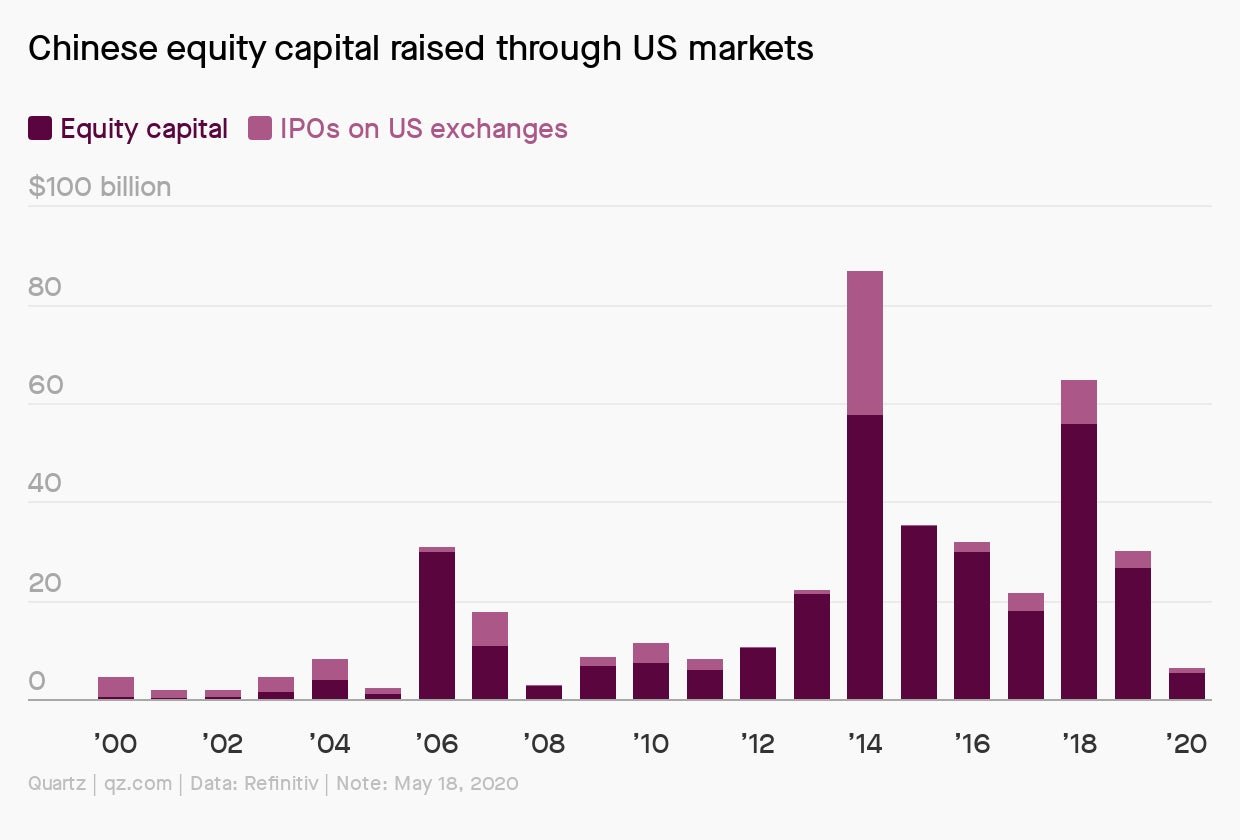

The future of US finance could very well be fewer Chinese stocks. US president Donald Trump wants to punish Beijing for the Covid-19 pandemic by (potentially) cracking down on Chinese listings. Meanwhile, American regulators worry that some countries, including China, don’t provide as much access to audits as they’re supposed to. The White House and the SEC may have different objectives, but they’re headed in the same direction.

“With the Trump administration, what the White House is saying and what career bureaucrats are doing can sometimes be quite different,” says University of Florida professor Jay Ritter, an IPO expert.

US officials have looked the other way as Chinese firms avoid the scrutiny that’s expected of US enterprises: for years, American regulators haven’t been able to inspect Chinese firms’ accounting audits, which is in line with directives from Beijing.

A regulatory shakeup looks increasing likely, and Nasdaq is tightening its standards. But as my colleague Jane Li and I wrote this week, it doesn’t seem likely that Chinese companies will get cut off completely. Wall Street doesn’t want to miss out on the next Alibaba IPO, and neither do American investors.

There are several reasons for Chinese companies to list outside their home market. US exchanges have prestige, and an IPO can include a fun (unless you’ve lived in New York) trip to Times Square or lower Manhattan. More importantly, Chinese executives like foreign markets because they leave a lot of money on the table when they list at home.

The reason is a quirk in market structure. Ritter says Chinese regulators essentially put a ceiling on the price-to-earnings ratio for stock market debuts. By keeping IPO prices artificially low, stocks can get a nice pop on the first days of trading, shooting up in value. (From 2014 to 2019, that “initial return” pop has averaged 284%.)

That’s nice for investors who get in on the IPO, but it’s not so great for executives who raise money there. Ritter estimates that Alibaba raised $4 billion more by going public in New York than it would have at home.

“Some of the Chinese regulations are designed to protect investors,” Ritter says, “but some of them go too far.”

This week’s top stories

♾ The Economist argues that the time has come for perpetual bonds (paywall). ️As governments borrow trillions of dollars to shield their economies from the pandemic, issuing bonds into infinity would simplify funding and reduce the need to refinance.

💶 Consumers in Germany can get paid to borrow, Reuters reports. The move, which is partly a gimmick from online lending platforms, comes as the ECB has provided banks with cheap money, offering them loans at negative interest rates.

😷 Financial titans set out their views this week. JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon says the pandemic has shown that “far too many people were living on the edge,” and that it’s time to build a more inclusive economy.

🤑 Former Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson writes that the threat from a digital renminbi is exaggerated, and the technology itself won’t lead the Chinese currency to challenge the US dollar. Instead, the biggest risk to the US currency’s reserve status “stems not from Beijing but from Washington itself.”

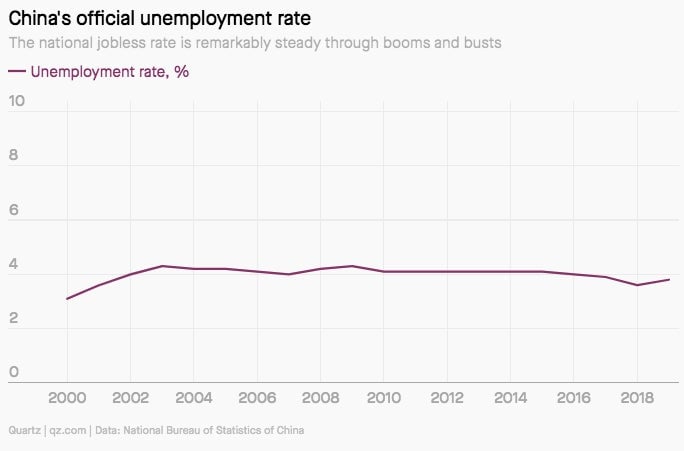

🇨🇳 Speaking of China, Quartz’s Mary Hui takes a look at the country’s inexplicably steady unemployment rate. A spike in joblessness could threaten the Communist party’s legitimacy, and some economists have dismissed official figures as almost meaningless.

The future of global trade

1870s: Levi’s creates the modern blue jean in San Francisco.

1930s: New York’s Garment District becomes home to the largest concentration of clothing manufacturers in the world.

1960s: Clothing factories start migrating to cheaper destinations overseas.

1980s: China’s economic reforms transform it into a leader in clothing production.

2000s: Clothing manufacturing expands to even cheaper Asian nations such Vietnam and Bangladesh.

Present day: The Covid-19 crisis forces brands and retailers to reexamine how they produce their goods, with the prospect of making clothes closer to home again.

Read more about what the production of jeans tells us about global trade disruptions in this week’s field guide for Quartz members. Not a member yet? Sign up for a seven-day free trial.

Always be closing

- Deel raised $14 million. CNBC reports that Andreessen Horowitz led the round of investment in the payroll platform for remote workers.

- Drivewealth, a financial company in the US, partnered with wealth management platform INDmoney to bring US stock trading to India.

- Visa bought a stake in GoodData, a data analytics company.

I hope your week has been a profitable one (pick your own metric). Please send tips, Chinese stock tickers, and other ideas to [email protected].