The Memo: The point of it all

What makes for meaningful work?

What makes for meaningful work?

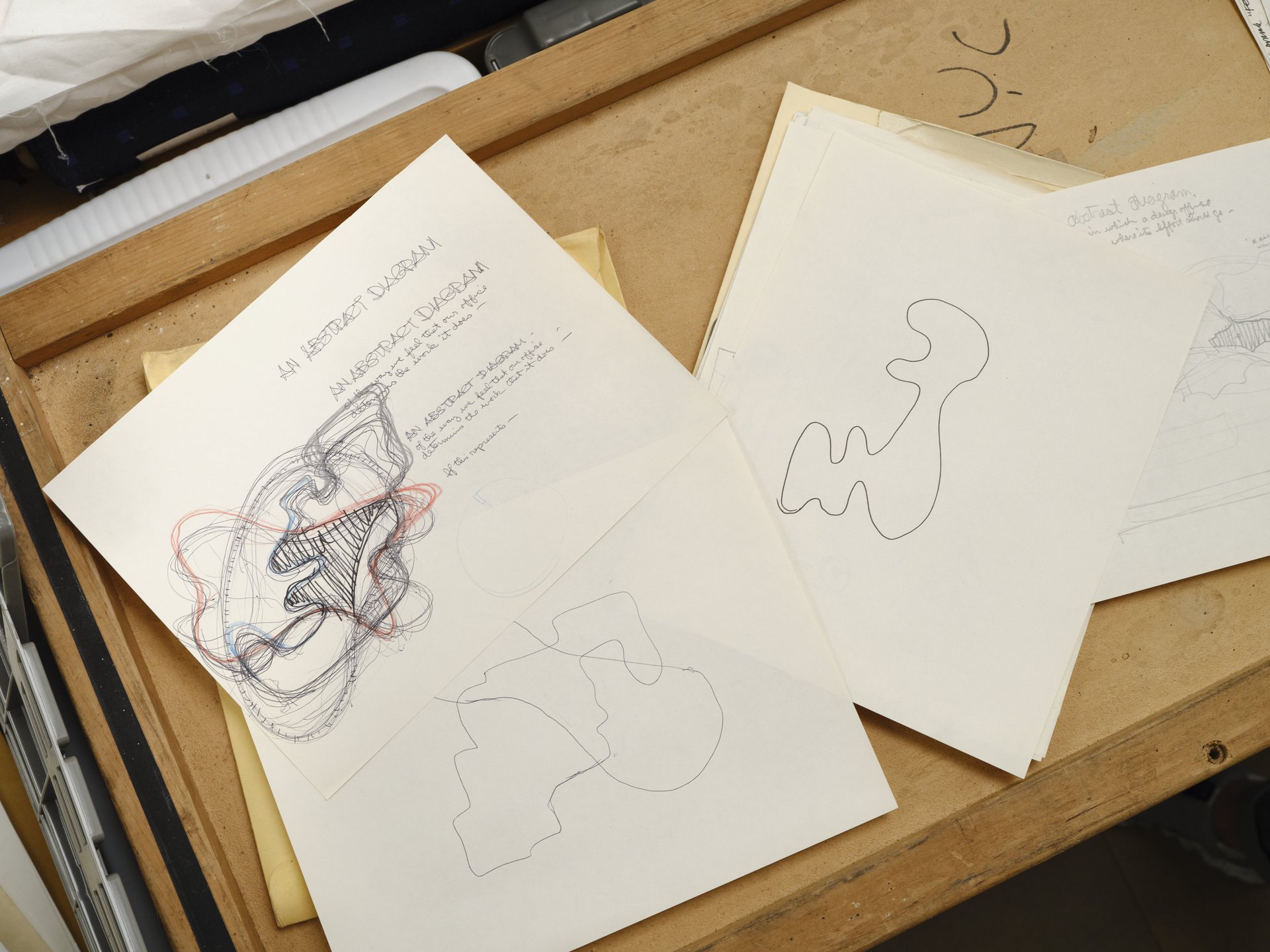

For design legends Ray and Charles Eames, finding purpose at work entailed satisfying three audiences: the client, yourself, and society.

In a hand-drawn doodle created for a 1969 exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, the Eameses explained that the process behind every project they took on—be it a new chair for Herman Miller, dorm furniture for Sears, a design audit for the Indian government, or an exhibition for IBM. First, they found common ground with the client, and together agreed on solutions that would satisfy business goals and benefit the most number of people.

“It is in this area of overlapping interest and concern that the designer can work with conviction and enthusiasm,” they wrote, pointing to the shaded section of the diagram.

The diagram—which the Eameses hung in their studio following the Paris exhibition—also defined the types of clients the sought-after husband-and-wife designers engaged with.

“We have found it is very helpful strategy to restrict our own work to subjects that are of genuine and immediate interest to us—and are of equal interest to the client,” Charles wrote in the text accompanying the 1969 exhibit. In the diagram’s captions, they outlined ecology, furniture, photography, filmmaking, and mathematics among their obsessions.

Prioritizing sustainable design before it was hip

The third factor, caring for common good, is a hallmark of the Eameses’ practice. They sum it up as a constant search for the best product for the most people, costing the least amount of money, effort, and material.

Long before sustainability became an industry buzzword, they pursued making consumer goods that were durable, repairable, and built with materials that didn’t harm ecosystems. Beyond handing off blueprints to manufacturers, the Eameses believed, designers had a responsibility to improve a product’s supply chain—from testing to manufacturing, production, packaging, and delivery.

The Eameses also bristled against the marketing hype characteristic of the design industry, which is still very much prevalent today. In his 1986 book, Business as Unusual, Hugh De Pree, Herman Miller’s former CEO, recalls a particularly feisty moment with Charles while reviewing the decor for their New York City showroom. Spotting a banner with the words “good design,” Charles scoffed: “Don’t give us ‘good design’ crap. You never hear us talk about that. The real questions are: Does it solve a problem? Is it serviceable? How is it going to look in 10 years?”—Anne Quito, design reporter

Five things we’re reading this week

⛱ Turn on your OOO. Goldman Sachs is giving its staff more paid vacation—and insisting they take it.

📅 Periods in the spotlight. The Spanish government is planning to offer several days of leave per month to people experiencing period pain.

🍼 Where is the support? Promoting breastfeeding as a solution to the baby formula shortage is misguided because it places all responsibility on the individual, not the system.

💻 Zoom is worth less than it was before the pandemic. The company’s stock price has fallen to pre-pandemic levels, down 83% from its all-time high in October 2020.

🧑💼 Russia may lose nearly 2 million jobs this year. As foreign companies flee Russia, employees will be cut loose in an economy where inflation is at a 20-year-high.

Quartz obsession interlude

Deconstructing dyslexia. Since dyslexia was first identified in the 1870s, psychologists, teachers, politicians, and parents have questioned its definition, its causes, and even its very existence. As a result, dyslexia is today known by enduring myths, which science is finally starting to debunk. 🎧 Learn more with this week’s episode of the Quartz Obsession podcast.

Listen on: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google | Stitcher

Ambiguity —> Creativity

In an excerpt from their book “Navigating Ambiguity,” Andrea Small and Kelly Schmutte of the Stanford d.school make the case for embracing the unknown.

Imagine it is 11,650 years ago. It’s the end of the Ice Age, and the Earth is warming up. You’re an early human, and you’re approaching a dark cave: There might be a saber-tooth cat in there, or it might serve as a cool shelter.

Your brain prioritizes the negative outcome (eaten by a saber-tooth cat) because your life’s on the line. “Our brains and bodies evolved to not die—evolution works from failure, not from success,” says professor of neuroscience and author Dr. Beau Lotto. Our species would be long gone if we hadn’t developed this little brain trick. But even though we’ve outlived the saber-tooth cats, a sense of uncertainty still generates a threat response in our limbic system.

This natural instinct to live is totally awesome. But it gives us a bias toward certainty and away from uncertainty. We have a natural tendency to prefer knowing over not knowing. The brain wants to make decisions based on the information it has and to complete the picture, even when it might be best to remain open.

When the brain can’t expeditiously complete the picture, we feel uneasy, lost, or anxious. Most people have a hard time admitting that they don’t know. There’s so much pressure put on us to have all the answers. Worse still is when we don’t even know if we’re answering the right question. Compound this with the surrounding pressures of life and work, throw in some constraints like time and money, and ambiguity mutates into anxiety.

But premature closure leads to reducing the richness of complexity, drawing faulty conclusions, and over-simplifying problems. And that leads to sub-par, mundane ideas.

Your brain naturally builds limiting beliefs about what is happening, and you must continually break through these ingrained beliefs to imagine something new. “And though that’s not particularly comfortable,” Patrice Martin, designer and former creative director at IDEO.org, says, “it allows us to open up creatively, to pursue lots of different ideas, and to arrive at unexpected solutions.”

You got The Memo!

Today’s Memo was written by Anne Quito and was edited by Francesca Donner.

The book excerpt was reprinted with permission from “Navigating Ambiguity: Creating Opportunity in a World of Unknowns” by Andrea Small and Kelly Schmutte and the Stanford d.school, copyright© 2022. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

The Quartz at Work team can be reached at [email protected].

Did someone forward you this email? Sign up for future installments here. Get the most out of Quartz by downloading our app and becoming a member.