For Quartz members—Who tells your story

Hi [%first_name | Quartz member%],

Hi [%first_name | Quartz member%],

You’re not confused—it’s Thursday! We’re trying something new here: Instead of closing out your week with a Friday morning newsletter, we want to give you a late week/early weekend companion for a relaxing cocktail or cup of tea.

Each week, we’ll be diving into a different theme, bringing you the smartest voices from inside our newsroom, and showcasing Quartz coverage. We’ll also tell you about you. For example, this week thousands of Quartz members read our story on how to build a walkable city. One (deeply relatable) member read the case for working from bed.

The room where it happens

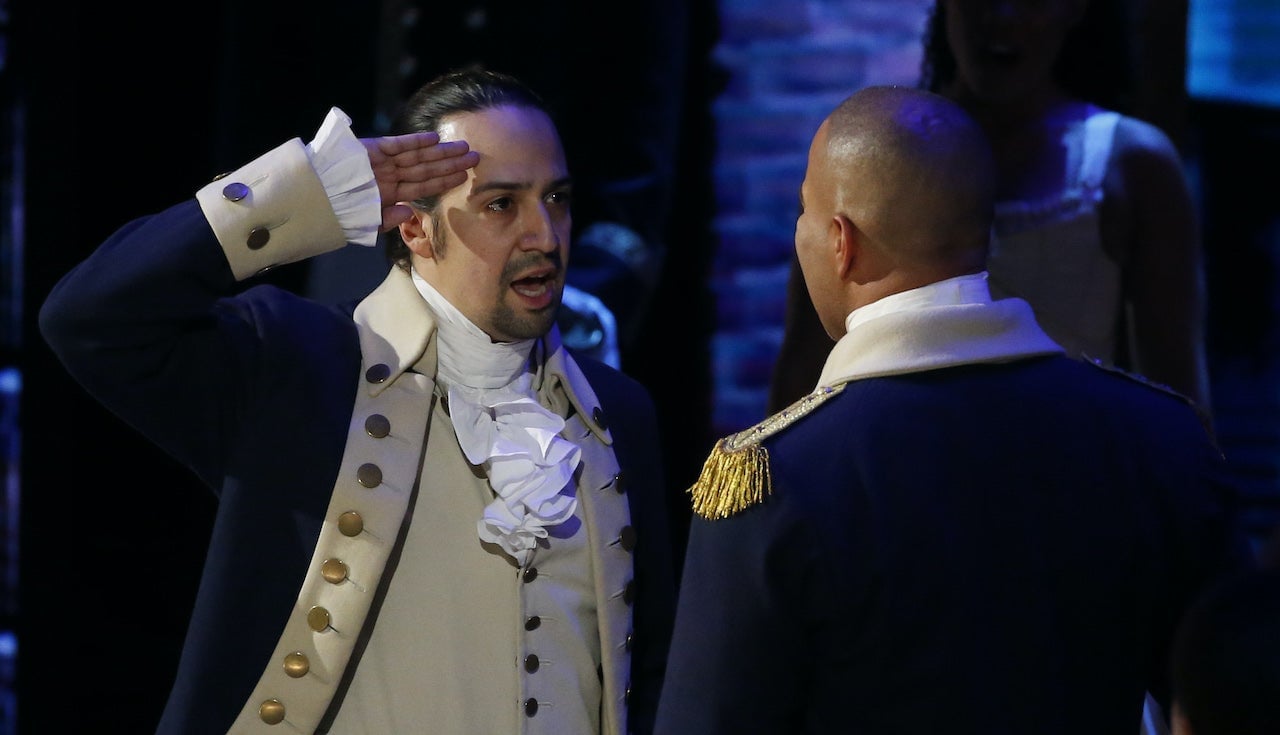

A filmed performance of the groundbreaking musical Hamilton hits Disney+ tomorrow. The Broadway show was correctly lauded for pretty much everything it did, not least of all creator Lin-Manuel Miranda’s decision to cast non-white actors as America’s founding fathers. But five years after its debut, Hamilton is still an outlier in the entertainment industry, which too often fails to represent the people who pay for theater tickets and TV subscriptions.

Half of the US moviegoing population is non-white, while only a quarter of on-screen characters are. The lack of representation is even worse behind the camera: Of the 1,200 highest-grossing films of the past decade, just 6% were directed by Black filmmakers and 4% by women.

For more than a century, the US entertainment industry has conditioned its citizens to believe the protagonist is always a white man—that everyone else exists in relation to him, supporting characters who serve only to advance (or thwart) his narrative.

The cost of this underrepresentation is incalculable. For better or worse, much of our education comes from the media we consume. TV and film help us relate to the world around us and place ourselves within it. When entertainment is not representative of that world, it perpetuates “dangerous misunderstandings,” as civil rights group Color of Change puts it, and “impedes justice efforts in the real world.”

If the industry players in charge of casting and hiring can’t be swayed by a sense of justice, then they also need to understand that improving representation is just good business. There is a growing body of evidence that diverse films perform better at the box office on average than their less diverse counterparts, despite the fact that the latter group gets far more funding and distribution.

The events of the last month in America have forced Hollywood and other global film industries to confront inequality with greater urgency. It’s true that they have made some recent strides in key areas. But those strides come too slowly and too inconsistently. A truly representative entertainment industry isn’t just a moral imperative, but, increasingly, an economic one as well. —Adam Epstein, entertainment reporter

By the numbers

Last year, the University of Southern California’s Annenberg Inclusion Initiative released a report looking at inclusion in the film industry between 2007 and 2018. Here’s what they found:

- 96% of the 1,200 highest-grossing films were directed by men. Among editors, 80% were white men. Among producers, 72% were white men.

- Only 3.6% of 2018’s top-grossing films were directed by women—down from 7.3% in 2017 and barely changed since 2007.

- One bright spot: More than 14% of the directors of the 100 highest-grossing movies in 2018 were Black, a 200% increase from just 7% in 2007.

Oh, the horror!

The Geena Davis Institute on Gender and Media has studied how positive and prominent roles for women in movies can motivate women in real life. It even used machine learning to develop a “GD-IQ” (Geena Davis Inclusion Quotient), which found that men in movies are seen and heard twice as often as women. With one exception: horror films.

After decades of victimizing its female characters, the genre is now more focused on women as survivors and protagonists, and scary movies as commentary on social issues. Here are just a few flicks that flip the script on the victimized woman trope:

- Rec (2007)

- Jennifer’s Body (2009)

- You’re Next (2011)

- American Mary (2012)

- The Conjuring (2013)

- Stoker (2013)

- The Witch (2015)

- Midsommar (2019)

Positive re: enforcement

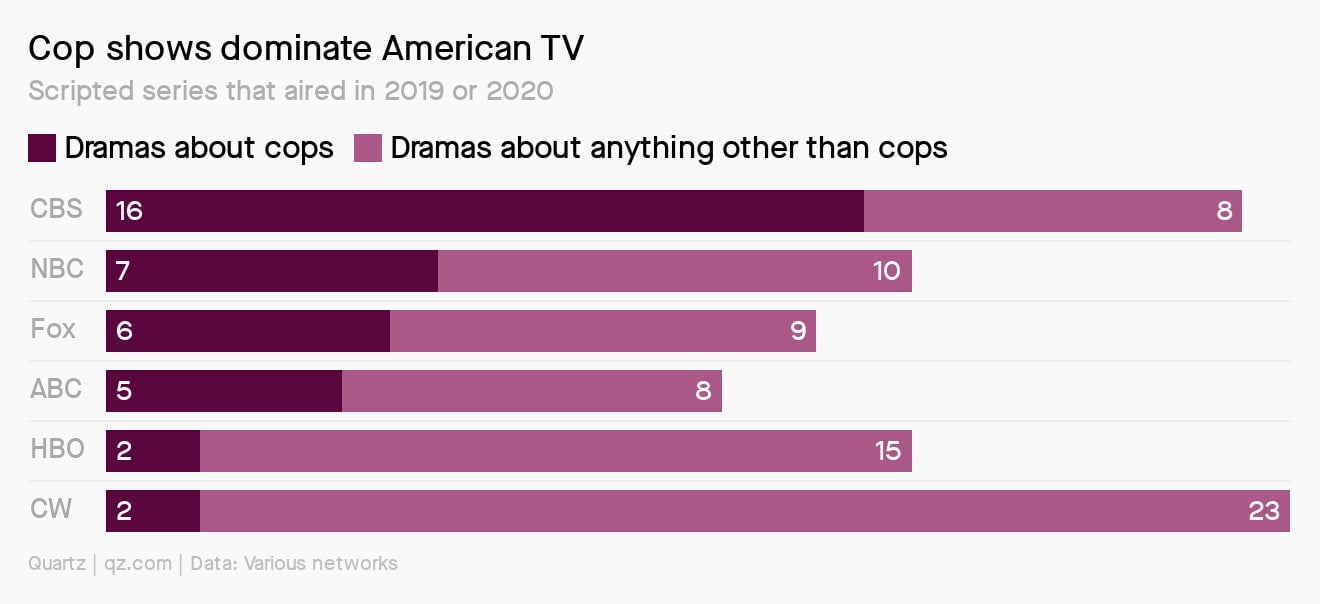

Perhaps one reason America’s reckoning on police brutality took so long is because TV is conditioning its citizens to view cops as reliable heroes. Numerous academic studies have shown that watching cop shows can lead to warped views of the criminal justice system and policing.

Of the 69 scripted television dramas that aired on the big four US broadcast networks (CBS, NBC, Fox, and ABC) in the last year and a half, 35 were about law enforcement, according to a Quartz analysis. CBS was responsible for 16 of those on its own. About 70% of the network’s dramatic programming from 2019-2020 were about cops.

Picture-perfect poverty

Should a show that’s already groundbreaking aspire to even greater levels of representation? For Quartz Africa this week, Norma Young says yes.

Blood and Water, one of the first domestic productions commissioned by Netflix specifically for an African audience, is set at a prestigious school in Cape Town, and focuses on South Africa’s burgeoning Black upper middle class. If you watched the show with no knowledge of the country, you might not realize the extent to which poverty is threaded into daily life there. Young argues that’s a problem:

Netflix’s investment in African entertainment has been welcomed…but this also means Netflix, with an original production budget of $15 billion, is in an unusually powerful position to enhance or distort reality about the continent. Shows like Blood and Water and Queen Sono are widely watched outside South Africa, and made available to all of Netflix’s 183 million subscribers around the world.

That’s poetic

Tailoring films to Western audiences can also shortchange their source material. When a trailer for the live-action remake of 1998’s popular animated film Mulan came out last year, audiences in China were upset that the adaptation once again diverged from the ancient ballad it’s based on, introducing an arranged marriage to the storyline.

For local audiences, Disney’s interpretation paled against the enduringly popular poem. “For generations, young Chinese students have been taught to recite the 400-word poem as a lesson in the importance of family [and] female power,” Echo Huang writes. “Regardless of the film’s storyline, the Ballad of Mulan’s message of what strong, independent women are capable of continues to resonate for people in China.”

A year later, the remake (the release of which has been delayed by coronavirus) nixed Mulan’s love interest, Captain Li Shang, in response to the MeToo movement, a decision that itself earned backlash.

So…how did you like the new format? Are there themes you’d be interested in exploring? What kind of cocktail did you drink?

Thanks for reading! Best wishes for a groundbreaking end to your week.