For Quartz members—AstraZeneca’s moment

Hi [%first_name | Quartz member%],

Hi [%first_name | Quartz member%],

Heard of a little thing called Covid-19? So has Big Pharma, and the race to develop a vaccine is on. It’s high-stakes geopolitical chess and every country and company involved badly wants to win, including Anglo-Swedish drugmaker AstraZeneca.

When Oxford’s Jenner Institute partnered with AstraZeneca on its vaccine candidate, ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, analysts scratched their heads. AstraZeneca is not a leader in vaccines, unlike its major UK competitor GlaxoSmithKline. It’s relatively small and has a tumultuous history. But if you look, the signs are there that AstraZeneca is building a blueprint to thrive as a 21st century pharma company.

First though, a poll! In celebration of two years of Quartz membership (🎉), we’re letting members decide which topic we cover in our Nov. 11 Obsession email. Click below on the rabbit hole you’d most like to fall down:

😍 Parasocial relationships: The kind of unrequited love where the other person doesn’t even know you’re alive? With social media making us feel even more connected to our favorite celebrities, parasocial relationships are big business.

👠 High heels: In the age of working, eating, and socializing at home, consumers might finally dump the pump.

🏡 Garage sales: Making money from junk—not to mention finding treasures among that junk—is a time-honored tradition that lets us become CEOs of our own industry, at least for a morning.

Not familiar with the Obsession email? You’re in for a treat. To get them directly in your inbox, sign up here.

Okay, roll up your sleeve and take out your symptom diary. We’re talking about AstraZeneca.

Flatlining: The early 2010s

About a decade ago, AstraZeneca (AZN) was in serious trouble.

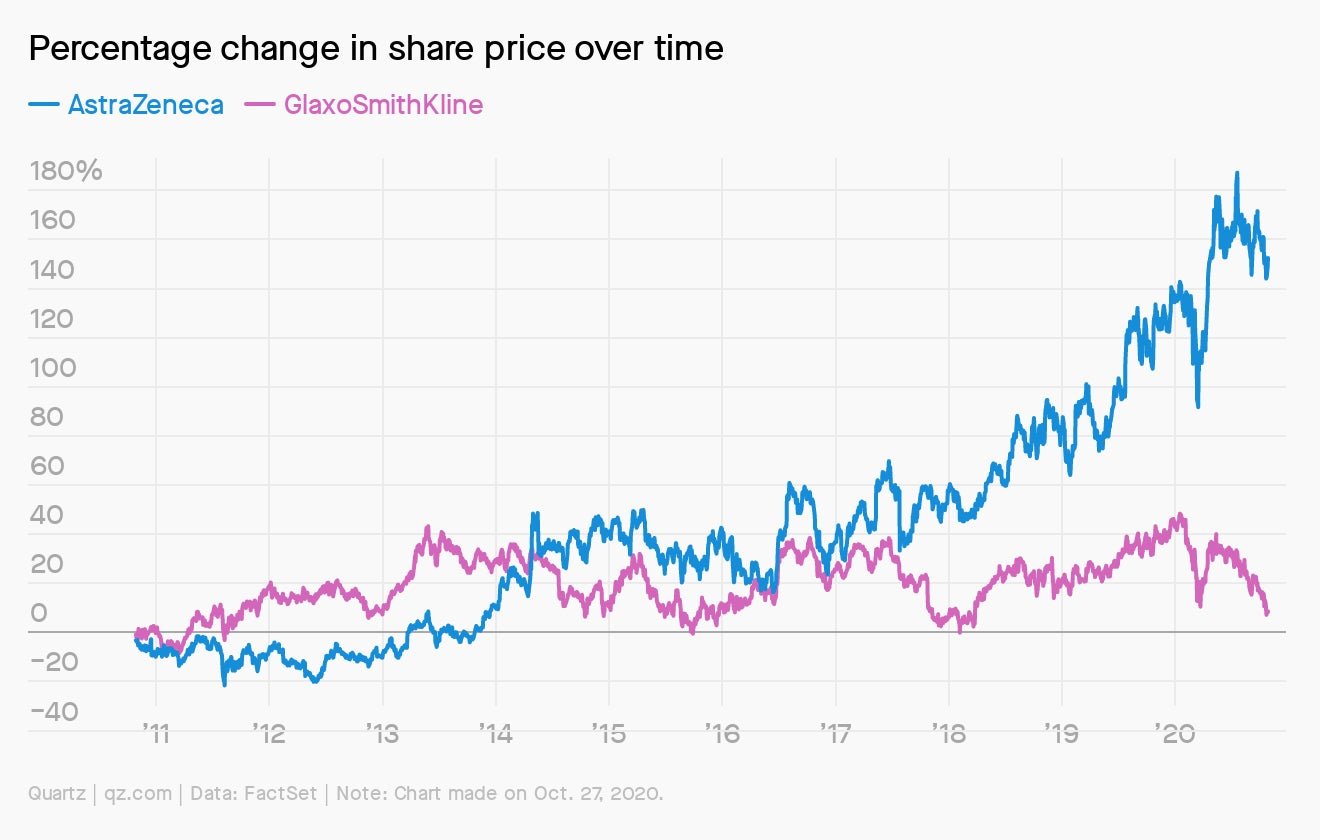

The company spent what analysts felt was too much money to buy vaccine maker MedImmune in 2007; it faced a so-called “patent cliff” for many of its key drugs; and several of the high-profile treatments it was developing failed during or right before late-stage clinical trials. Between 2007 and 2012, AstraZeneca cut more than 20,000 jobs, banned non-essential travel for employees, and closed an R&D site in the UK. In the fall of 2012 its market valuation stood at £36.6 billion ($47.7 billion), just over half of GlaxoSmithKline’s £70.9 billion.

Investors revolted, and the first head to roll was CEO David Brennan, who resigned hours before a shareholders meeting in April 2012. Six months later, AstraZeneca hired Frenchman Pascal Soriot, formerly of Roche, to replace him.

In 2013, US pharma giant Pfizer, smelling blood, approached AstraZeneca about a £58 billion acquisition. AstraZeneca said no, but Pfizer kept trying. The rumor was that Pfizer wanted to avoid US taxes on its foreign earnings, and buying Astra would allow the company to do that while benefiting from the UK’s comparatively low corporate tax rate.

Soriot believed he could turn AstraZeneca around if investors gave him some time. He even staked his personal credibility on it, promising to get to $45 billion in annual sales by 2023. In May 2014, his board rejected Pfizer’s final £69 billion offer. At £55 per share, it was roughly 18% more than Astra’s share price around the time the takeover bid was announced.

This marked a new chapter for AstraZeneca.

View from the top

Pascal Soriot isn’t your typical Big Pharma CEO. Here are a few surprising and interesting facts about the 61-year-old Frenchman:

⚕️ He trained as a veterinarian even though his mom wanted him to be a doctor. Relatable.

🥊 He told The Times of London that he was often involved in “bare-knuckle street fights” growing up.

🇦🇺 He has a house in Sydney and considers himself “practically Australian” (don’t tell the French).

🎥 His favorite film is Braveheart and his go-to musicians are Bruce Springsteen and Damien Leith.

🌍 His “leadership hero” is Greta Thunberg.

2015-2020: Riding on a high

By the mid-to-late 2010s, AstraZeneca still lagged behind its competitors. In 2017, the market got spooked by rumors that Soriot was jumping ship for Israeli drugmaker Teva and a few months later a promising (and expensive) lung cancer drug candidate failed in late-stage trials. Soriot has since called 2017 “the pivotal year” (link in French) for Astra.

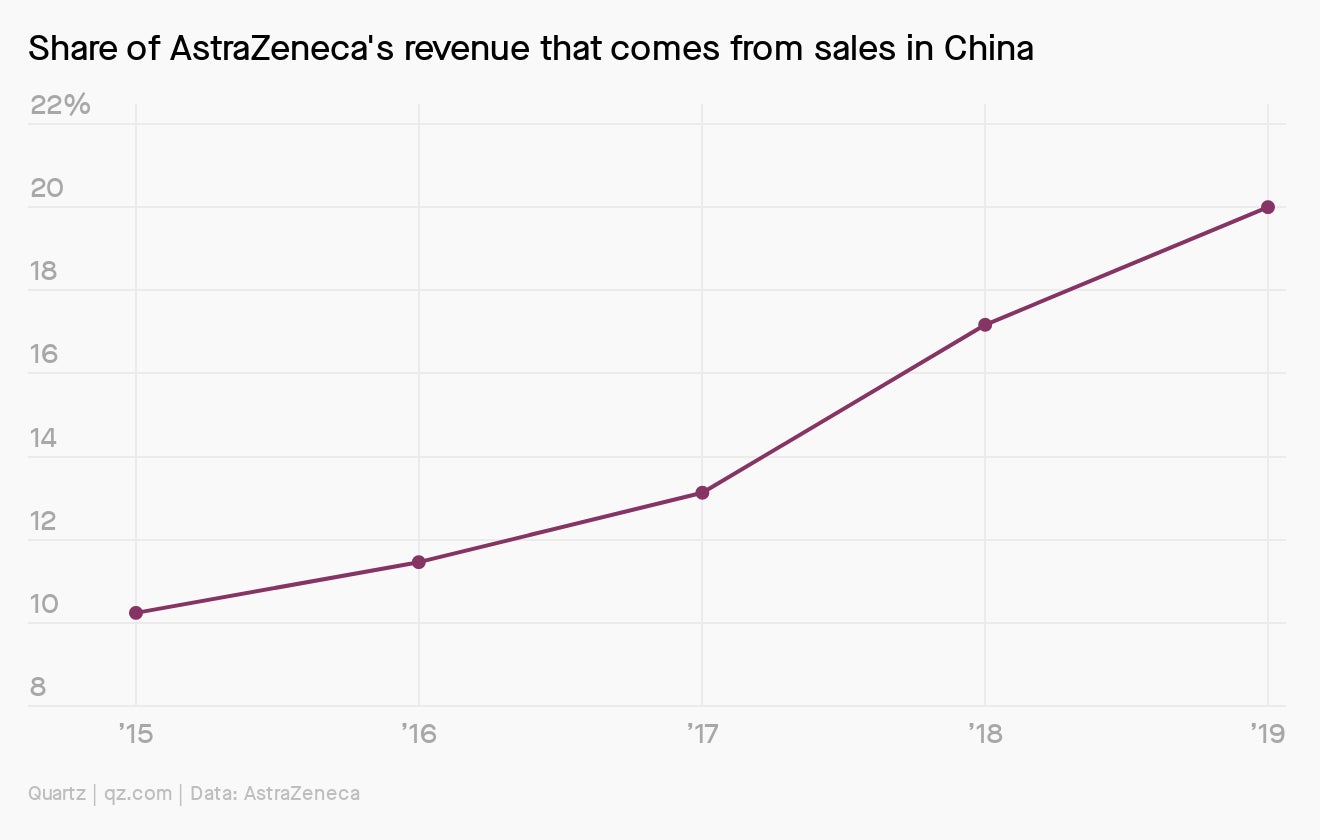

Following an internal review, the company decided to concentrate on three key areas: respiratory, oncology, and cardiovascular medicine. In 2019, Soriot announced a major reorganization of AstraZeneca’s R&D and commercial units to focus on biopharmaceuticals and oncology, sparking a string of high-profile departures from the company. But some smart investments, the reorganization, and a pivot to China started to pay off.

Then Covid-19 happened. On April 30 of this year, Oxford University announced it would partner with AstraZeneca to develop and distribute Oxford’s coronavirus vaccine candidate. While Astra has a small vaccine pipeline, analysts considered it an interesting choice. As Fidelity’s Emma-Lou Montgomery put it, GlaxoSmithKline, “the world’s biggest vaccine manufacturer by sales, would have probably been the more obvious partner.”

Early results showed an immune response and low adverse effects in adults. But the project was paused in September when a participant developed an inflammation of the spinal cord. Trials in the UK, Brazil, and South Africa restarted pretty quickly, but the US Food and Drug Administration suspended AstraZeneca’s US trial for six weeks pending an investigation. It gave it the green light to restart last week, finding that the illness wasn’t related to the vaccine.

Success would certainly boost investor confidence and AstraZeneca’s profile, even though it has pledged not to make a profit from the vaccine “during the course of the pandemic” (take that with a grain of salt). After all, who wouldn’t want to invest in the company that saved the world?

By the numbers

£104 billion: ($134 billion) AstraZeneca’s market valuation as of Oct. 29, compared with GSK’s £66 billion ($85 billion).

£14 million: ($19 million) Soriot’s 2019 pay, including bonuses and equity. Soriot used to complain that he was the lowest-paid CEO in his industry; it’s been a major point of internal tension.

15.7%: How much more, on average, male AstraZeneca employees in the UK were paid per hour than women in 2019.

>3,100: AstraZeneca employees who have PhDs.

60%: The percentage of Americans who say they don’t trust pharmaceutical companies to look out for their best interests.

All in on 🇨🇳

AstraZeneca opened its first office in China in 1993, and has since become one of the most active foreign pharma firms in the country, with three offices and two manufacturing plants employing more than 20,000 people. It has brought 40 products to market in China and invested $1 billion there.

China is a tough market for foreign firms to compete in, and that’s been especially true of the healthcare sector. But recently the government has made it easier for multinationals to sell their innovative molecules there—albeit at a discount. Last year, China’s national health body green-lit one of AstraZeneca’s drugs for reimbursement, but Bloomberg reported it was only after the company agreed to cut the price by 61% (not such a bad deal when measured against China’s potential market of 1.4 billion people.)

AstraZeneca now brings in as much profit from China as it does Europe, and it will soon be more, according to Soriot, who’s very bullish about the country—for good reason. China is the El Dorado of Pharma: It’s got a massive aging population and an emerging middle class demanding the best drugs money can buy.

But if it was that easy to strike gold in China, everyone would do it. Foreign firms still remember when Chinese authorities fined GlaxoSmithKline nearly $500 million in 2014 for bribing doctors and officials and laundering the money through travel agencies. Since then many firms have pared back their China operations. As David Zweig, emeritus professor at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, put it at the time, “everyone else pays bribes. Glaxo just got caught.”

AstraZeneca has already gotten into trouble because of its activities in China. In 2016 it paid the US a fine of $5.5 million for allegedly violating the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (pdf), notably by bribing officials and writing off the kickbacks with shady accounting. (Nor is that AstraZeneca’s only brush with US authorities.)

But Soriot doesn’t seem worried about these hiccups, or the trade war between Washington and Beijing. In an interview with French outlet Les Echos (link in French), he said that “the positive aspect of the trade war with the United States is that China is opening up to the world.” And, by extension, to AstraZeneca.

Keep reading:

- Pfizer’s CEO says his vaccine candidate is in the “last mile.”

- AstraZeneca and the challenges of mass-producing a Covid-19 vaccine.

- How the business interests of vaccine trials work against people of color.

- Bloomberg’s turnaround profile on AstraZeneca (🎥)

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or companies you want to know more about.

Best wishes for a pivotal end to your week,