For members—The most metal way to compete with China

Hi Quartz member,

Hi Quartz member,

Lynas has been described as both “tiny” and “small,” but as the world’s largest rare earths producer and processor outside of China, the Australian company occupies a pivotal position in the global economy. It has a mission to match: diversifying global rare earths supply chains and reducing the world’s reliance on China for the critical metals. No pressure!

First, a recap: India’s central bank has no faith in cryptocurrencies, the EU is sitting on millions of unused vaccines, and Disney’s CEO says the pandemic has changed movie releases forever. Gary Gensler’s view of bitcoin hinges on a 55-year-old financial rule, and Tesla remains the most shorted stock in the world. The pandemic’s best innovation? Private movie theater rentals. Rooftop solar? It could kill or save the Texas electric grid. The future of e-commerce? Coming to a Target near you.

Your most-read story this week: A new rule is about to make PPP loans more generous for businesses without employees. And the most kindhearted member goes to anyone who takes this three-minute survey to help us improve your Quartz experience. (Psst, there’s a chance to win a $100 Visa gift card.)

Okay, now make your way to the nearest collapsed volcano. We’re digging into Lynas.

Earths, grind, and fire

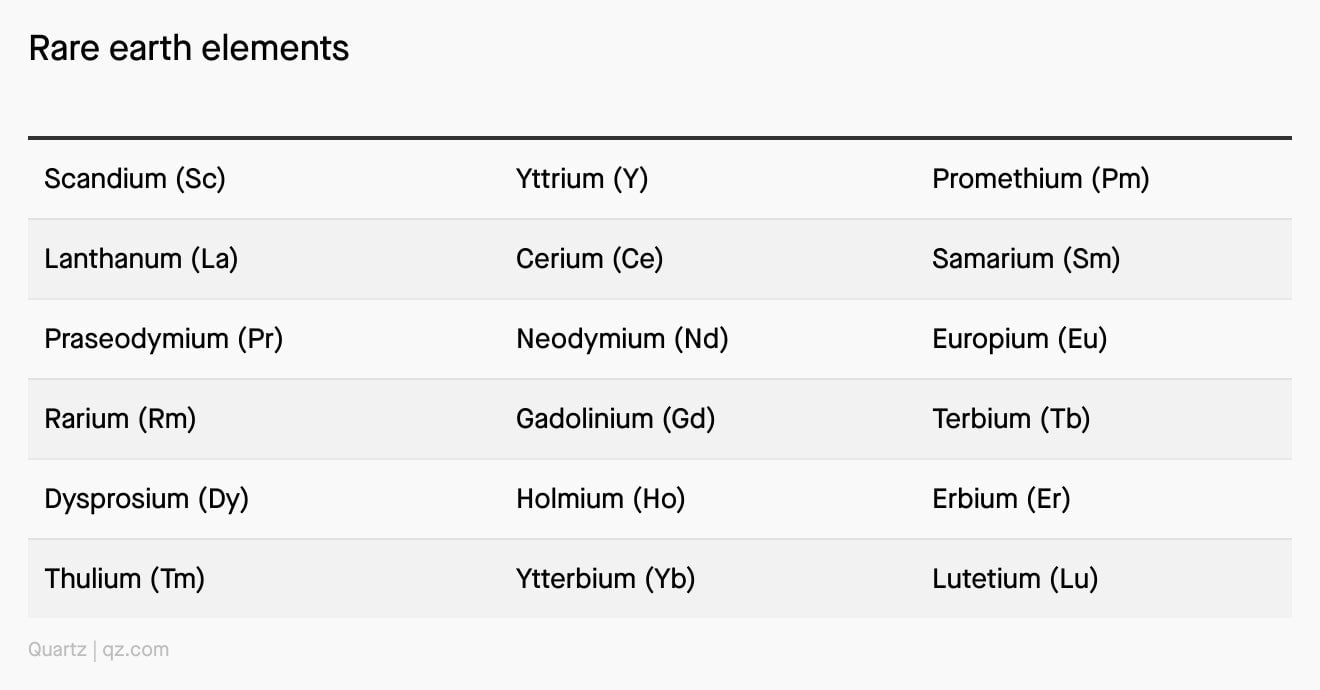

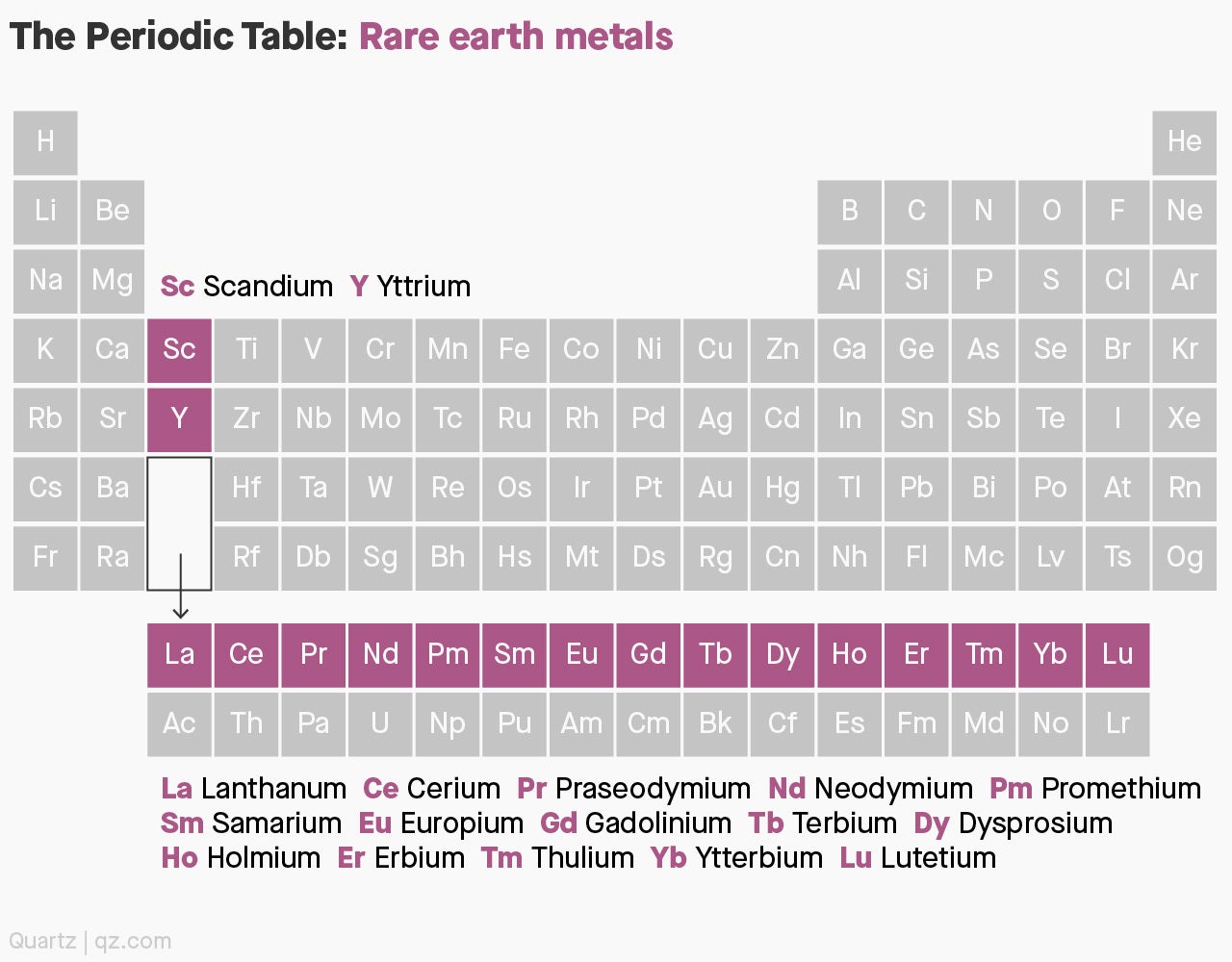

If you’ve spent the first 200 words of this email wondering what rare earths are, worry not: Rare earths refers to a group of 17 metals crucial to the manufacturing of many electronic products that power the global economy, including cell phones, electric vehicles, aircraft engines, and wind turbines. There are “light” and “heavy” rare earths, based on their atomic number, and global demand for these metals is climbing.

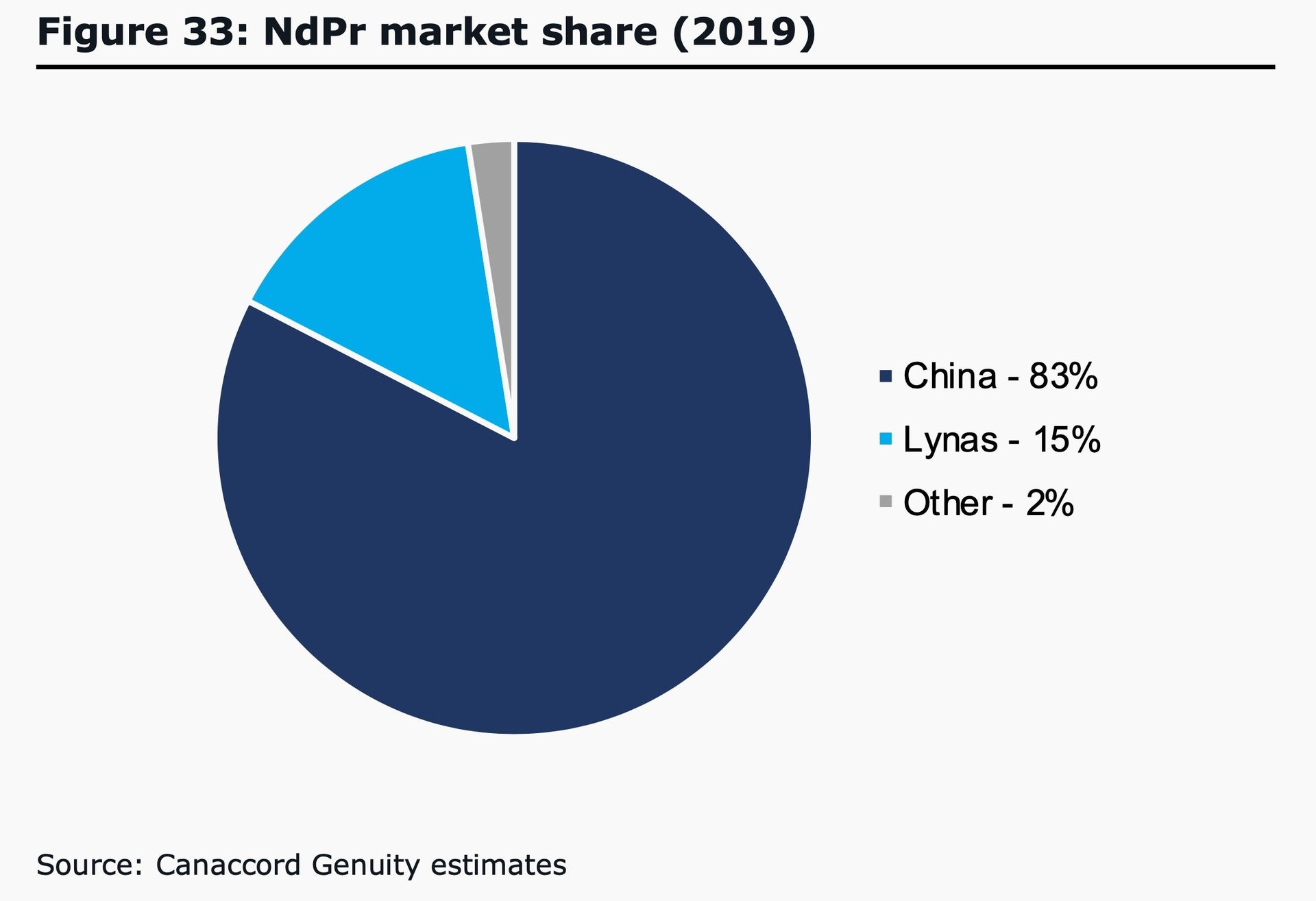

China currently dominates the global rare earths industry, and was responsible for some 60% (pdf) of world production last year. That poses a problem for countries, like the US, that are highly reliant on China for imports of these critical metals. While no one country or company will single-handedly diversify global rare earths supply chains, Lynas does have a big role to play. “As the world’s largest ex-China producer, its strategic importance cannot be overstated,” one analyst wrote in 2019.

How did Lynas get here? The 38-year-old company owns the Mt. Weld mine in Western Australia. The mine is an ancient collapsed volcano, and one of the largest and highest-grade rare earths deposits in the world.

Ores mined at Mt. Weld go through some preliminary crushing, grinding, and floating at the site to upgrade their rare earth concentration to roughly 35% to 40%. Next, that concentrate is shipped to Lynas’s processing plant in Malaysia. The concentrate is cracked in a hot kiln, leached with water to remove impurities, separated into individual rare earth elements, and finally refined into high-purity rare earth metals. That final product is then sold to customers, who use them in high-tech applications like the permanent magnets used in motors and hard drives, catalysts for oil refining, and batteries.

All that processing in Malaysia does leave behind slightly radioactive waste, and fears of environmental contamination drove public opposition against Lynas a decade ago, as Malaysian residents and environmentalists demanded their government bar the company from local operations. Though Lynas ultimately received permission to operate the plant, it now has until 2023 to relocate the facility. The company has identified a site in the outback city of Kalgoorlie-Boulder, where an environmental assessment and approval process is underway.

Brief history

1983: Lynas is founded by Australian businessman Nicholas Curtis.

1986: Lynas lists on the Australian Stock Exchange under the ticker symbol LYC.

2009: A Chinese state-owned company tries to buy a majority stake in Lynas—a move that would have cemented the country’s grip on the global rare earths industry—but Australia blocks the bid on national security grounds.

2011: Soaring rare earths prices amid Chinese export restrictions push Lynas shares to an all-time high of over AU$24 ($19). Shares plunge when the rare earths bubble bursts later in the year.

2014: Amanda Lacaze is appointed as the new CEO of Lynas, having previously worked in telecommunications and served as CEO of the Australian arm of internet provider AOL.

2016: Japanese lenders, who struck an investment deal with Lynas in 2011, restructure the deal to save the ailing Lynas from going bust.

2017: Lacaze delivers what she calls the firm’s first “champagne quarter,” slashing losses and boosting sales by 108% compared to the same quarter in 2016.

2020: Lynas signs a contract with the Pentagon to examine setting up a rare earths processing facility in the US.

Pop quiz

Seventeen of these 18 rare earths are real, and one of them we just made up. Can you guess which one?

Okay fine, there’s no such thing as rarium. Here’s where you can find all the real rare-earth elements on the periodic table.

The biggest slice

Lynas is the world’s second largest producer of neodymium (Nd) and praseodymium (Pr), both light rare earths. Used together, they form NdPr, an alloy that’s present in a magnet inside the iPhone. Lanthanum (La) and cerium (Ce), two other light rare earths, make up over 70% of the Mt. Weld reserves. Both are used to polish iPhone screens.

A rare opportunity

How do we bring women back to the workforce? On March 10 at 12pm US eastern time, Quartz editor in chief Katherine Bell will tackle this question alongside Minnesota senator Amy Klobuchar, Path Forward executive director Tami Forman, and Wonderschool co-founder Chris Bennett. The inaugural episode of a new Quartz event series—Make Business Better—our discussion will explore actionable policy solutions and what companies can do to support women’s reentry. Register now to join in.

920 lbs: Rare earths in a Lockheed Martin F-35 fighter jet

9,200 lbs: Rare earths in a Virginia-class nuclear-powered attack submarine (pdf)

8: Number of different rare earths in a typical iPhone

98%: Proportion of rare earths materials in the iPhone 12 that are recycled (sourced from an outside supplier that recovers rare earths from discarded products) (pdf)

1: Active rare earths mines in the US

80%: US rare earths imports sourced from China (pdf)

2018: Year China became a net importer of rare earths

37%: Known global rare earths reserves held by China (pdf)

Person of interest

“I think the Chinese have given us a case study in developing rare earths. They did not let a thousand flowers grow [to compete with them].” —Lynas CEO Amanda Lacaze

Lacaze’s first full-time job was working as a Marlboro girl, decked out in a skirt, bolero, and cowboy hat. Within weeks, she was promoted to sales representative; within two years, she was a field sales manager overseeing six people. By that point, Lacaze told the Australian Financial Review, she knew she eventually wanted to be a CEO.

Fast forward to 2014: Lacaze takes the helm of Lynas as the company is, as she put it, “in a fair bit of trouble.” Just over a year later, Lynas is hailed as “the comeback kid in rare earth.”

Big in Japan

Japan is arguably Lynas’s most important partner. When China cut rare earths supplies to Japan in 2010 over a fishing trawler dispute, Tokyo realized it had to secure the critical metals from elsewhere.

In 2011, a top Japanese trading company and a Japanese state-run agency signed a deal to invest $250 million in Lynas, in return for a steady supply of rare earths. (The terms of that deal were revised several years later to save Lynas from collapse.) Japan’s efforts have paid off: A decade ago, it imported 82% of its rare earths from China; last year that that number stood at 58%. Lynas accounts for 30% of Japan’s supplies.

Lynas is building its alliance with the US, too. The US defense department last month awarded the company $30 million to set up a rare earths processing facility in Texas. That’s in addition to the Pentagon granting funding last year to a joint venture between Lynas and Texas-based Blue Line to separate heavy rare earths in the US. Currently, China is the only country with the capacity to separate heavy rare earths.

With US president Joe Biden’s executive order to secure critical supply chains, including those of rare earths, Lynas will have its work cut out for it.

Keep learning

- Read about a Chinese rare earths giant building alliances worldwide.

- Dive into this report on China’s rare earths strategy.

- Watch this interview with Lynas CEO Amanda Lacaze…

- …and read this Q&A with her.

- Check out the steps the US is taking to break China’s monopoly…

- …and consider Australia’s role in working towards that goal.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or companies you want to know more about.

Best wishes for a rare and valuable end to your week,