For members—The air you breathe

[qz-guide-hero id=”434623075″ title=”💡 The Big Idea” description=”2020 taught us to care about air—and the air in your home and office could be harming your health.”]

[qz-guide-hero id=”434623075″ title=”💡 The Big Idea” description=”2020 taught us to care about air—and the air in your home and office could be harming your health.”]

By the digits

2.5 microns: A commonly-measured size of particles that make up fine particulate matter (PM2.5), which, when inhaled over time, are the most damaging to human health

98%: Cities of more than 100,000 inhabitants in low- and middle-income countries where the air exceeded the WHO’s recommended levels of PM2.5 in 2016

56%: Cities of more than 100,000 inhabitants in high-income countries where the air exceeded the WHO’s recommended levels of PM2.5 in 2016

6-8: Air changes per hour (a metric for ventilation) recommended in an office

0.35: Air changes per hour in a typical home

1.3: Maximum air change per hour in a home with a window open

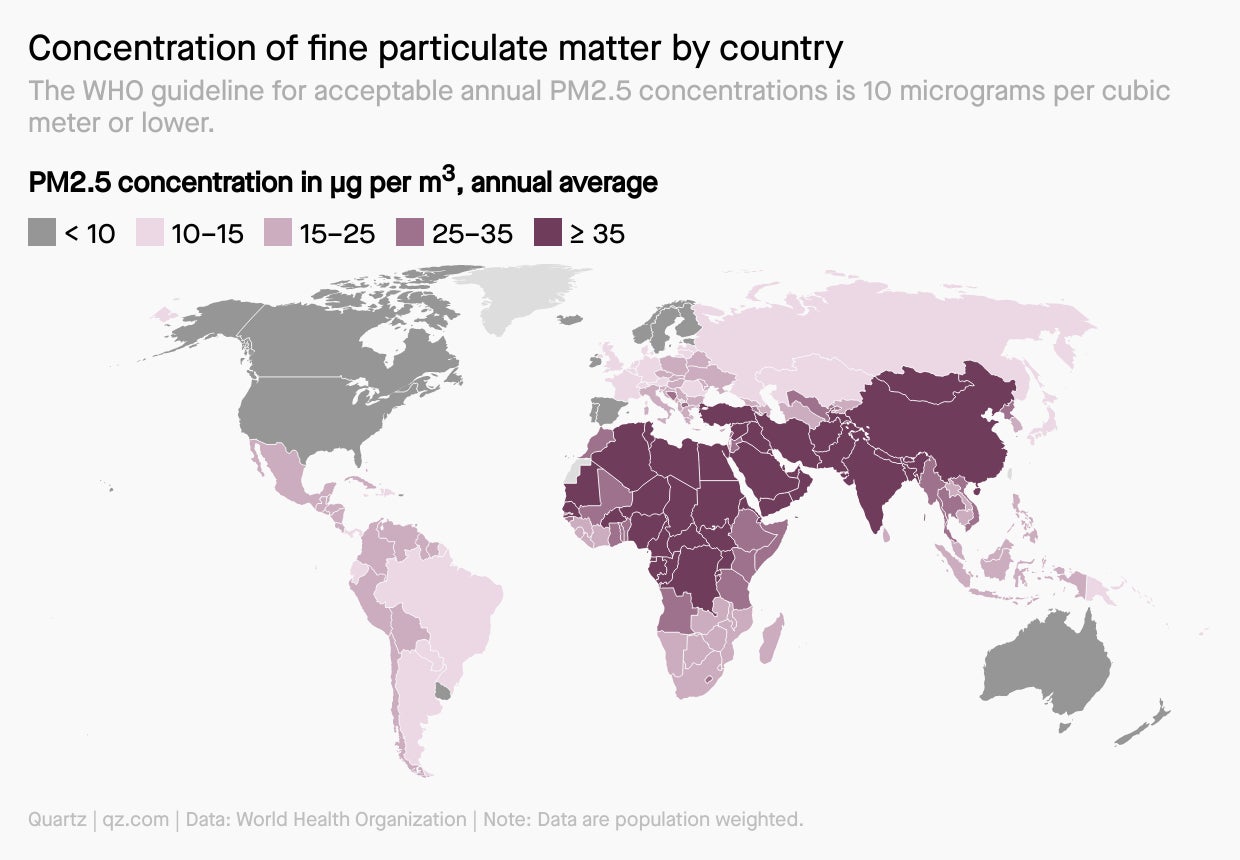

Charting air pollution by country

When it comes to the air you breathe, your location matters. While no city, state, or country is completely free of air pollution, some have better outdoor air quality than others. And the quality of the air outside affects that inside, which is where most people spend most of their time.

One big number

90%: Proportion of one’s life spent indoors. During the pandemic, for some that was likely closer to 100%.

What affects indoor air quality?

You and everything you do. Your space and everything in it. Your neighbors. All of this can contribute to the quality of your indoor air. Here are some common things that can add particles and gases to the indoor environment.

💨 Outdoor air

🐕 Pets

🛋️ New furniture

🚬 Smoke

🧽 Cleaning products

👃 Other scented products

The billion-dollar question

Will a move from the city to the country improve my health?

Scientists are still debating just how much damage can be averted by relocating from an area with high air pollution to lower air pollution.

There’s some reason to believe that relocating for a short time period—say, a vacation—can reduce some of the more acute risks from heavily polluted air. For example, people who are predisposed to asthma or heart attacks are less likely to have one while breathing cleaner air.

The effects of a permanent relocation, however, are harder to quantify. Because we know air pollution is linked to acute and chronic health conditions, researchers can’t ethically expose people to it. Instead, they conduct observational studies in which they measure the ambient air quality of an area and record various aspects of residents’ health.

It’s hard to isolate air quality from dozens of other variables. But scientists are confident enough that better air quality will improve public health that they’re starting to look at how to do it.

Brief history of healthy buildings

1854: Florence Nightingale reduces the mortality rate in a Crimean hospital by spacing out the beds, opening windows, and sanitizing the space.

1918-1919: The Spanish flu kills 20 to 50 million people worldwide in one of the deadliest of a series of influenza pandemics of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

1902: The first modern air conditioner is invited by Willis Haviland Carrier. Air conditioning has made life bearable for many people but it has come at a high cost for the environment.

1931: Modernist Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier publishes Towards a New Architecture, which details an ideal modernist home as being “full of light and air.”

1950s: Architects begin using cheaper and more industrial materials in buildings, which scientists have more recently discovered can be toxic.

1980s: Buildings were designed for an exterior look, ignoring what was going on inside. “Sick building syndrome” enters the lexicon.

Late 1990s: The green building movement, intended to promote environmentally sustainable buildings, was born.

2010: The green buildings movement embraces the notion of Healthy Buildings, which keep both environmental and human health in mind.

Did you know?

Cooking is a common activity that generates harmful airborne particles. In India, for example, many families cook indoors using solid fuels like coal that can cause lung cancer.

A simple solution to this problem is to: Use a cooker hood. They’re standard issue in many homes, but many people don’t use them, likely because they don’t understand how beneficial they can be.

DIY: How to improve the quality of the air you breathe

Compared to other indoor settings, many homes have few “air changes per hour,” a metric engineers use to assess ventilation. As a result, air pollutants can pile up. Here are some ways to reduce that buildup so the air in your home.

🌀 Don’t hate, circulate (the air)

👟 Keep shoes outside to prevent tracking dust or dirt inside

🕯 Air out rooms after burning things like candles, incense, or cigarettes

Listen up!

The only group that has thought more about the air you breathe than doctors, scientists, and public health experts? Musicians. Listen to this playlist about all things air while you read the guide.

📣 Sound off

Are you worried about the air quality where you live?

In last week’s poll about work a year into Covid-19, 74% of respondents predicted we’d be primarily working in a hybrid (mix of home and office) model 10 years down the line. Sounds pretty good to us.