For members—Is it time to farm at the office?

Hi Quartz member,

Hi Quartz member,

The year is 2030; food scarcity is common and so is inflation. But since setting a goal in 2019 to produce 30% of its food internally, Singapore is as prepared as anywhere could be. One small piece of that plan: Sustenir Agriculture, whose indoor vertical farms can be retrofit into existing buildings, including offices. Fresh kale in the supply closet? Yes please.

But first, a recap: Foreign aid for India’s Covid crisis keeps getting lost in the mail, Biden’s first climate regulation is supported by Republicans, and Hollywood studios are making a desperate plea to get people back in theaters. Employee stock ownership has arrived on Africa’s startup scene, and the semiconductor shortage can be explained by the bullwhip effect. Where are India’s billionaires? Has the UK reached herd immunity? Is it time to talk about menopause at work? Asked and answered.

Your most-read story this week: The founder of Moderna doesn’t think vaccines are all that impressive. And hey, we launched a new feature! (Well, officially launched; you already got a sneak peak.) It’s called Quartz Essentials, and it’s a new way of extracting knowledge from the news. Learn more here, or just keep your eyes peeled for Essentials at the end of articles you read on the site.

Okay, now clean out your closet and get ready to grow tomatoes in it. We’re farming, vertically.

Retrofitting in

The necessity of securing food during crises and preserving land for a livable climate is changing the focus of farming from rural areas to cities. At the forefront of this shift is Singapore, a city-sized country that aims to produce 30% of its own food by 2030.

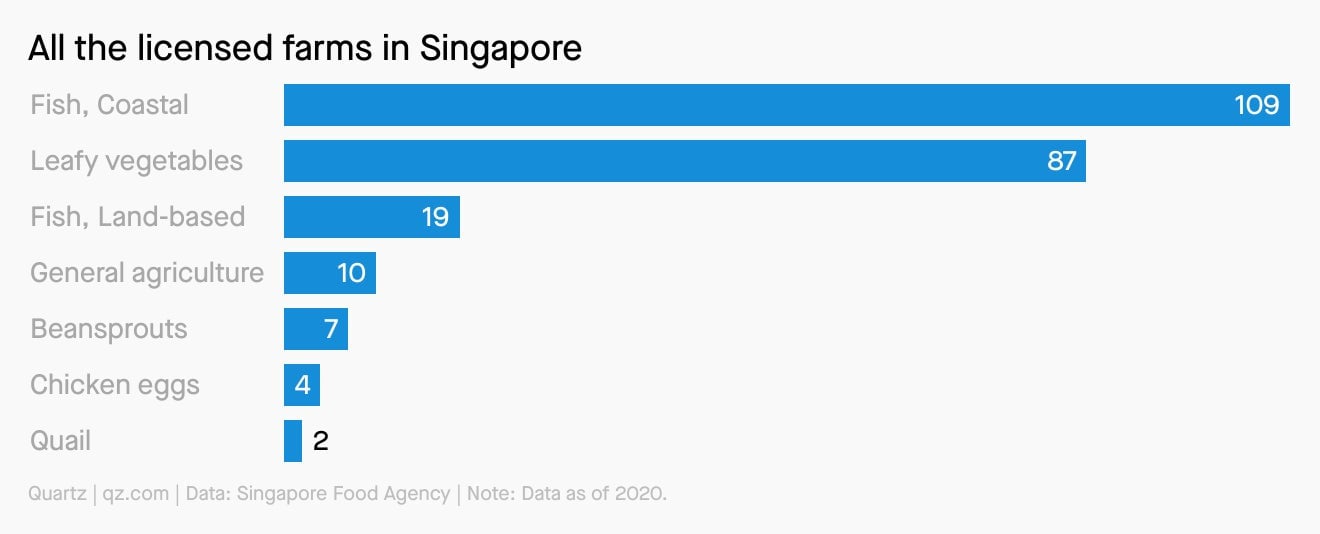

With 90% of Singapore’s food currently coming from abroad, the challenge is a tall order. Decades of urbanization have left no more than 1% of arable land for conventional farming in the country, a challenge that demands creative solutions. Singapore’s “30 by 30” plan calls for everyone to grow what they can, and the government is providing $21 million in grants to companies whose technology supports faster production, in alternative farming spaces, of things like eggs, leafy vegetables, and fish.

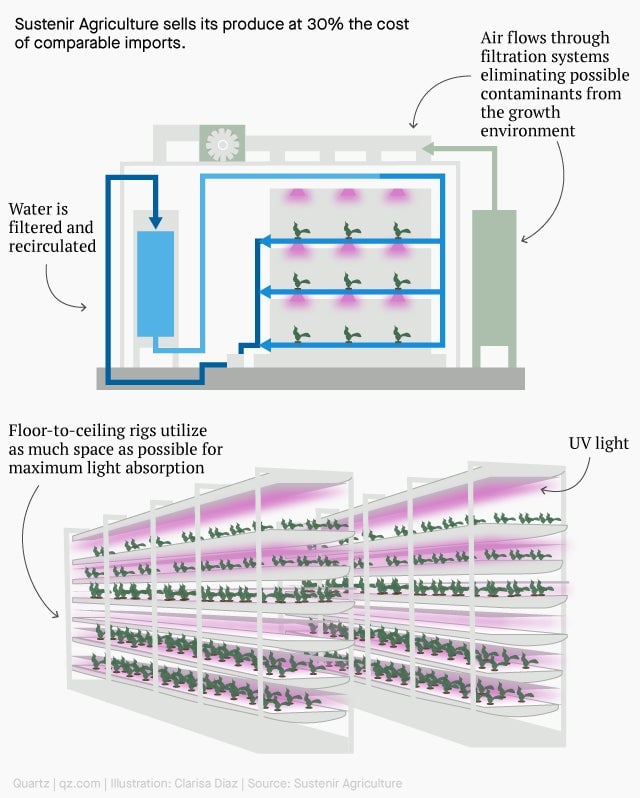

Cue Sustenir Agriculture, a nine-year-old startup that converts existing indoor spaces into vertical farms. The company currently operates three farms: in Singapore, Hong Kong, and Malaysia. Products grown there—including kale, arugula, and a delicious-sounding kale-apple-carrot juice—are available in multiple local grocery stores, often at 30% of the cost of imported produce. Long term, Sustenir is hoping to own retrofitted building-farms in cities all over Asia.

Starting out in a Singapore basement, founder Benjamin Swan and his business partner Martin Lavoo experimented with techniques Swan learned from traveling to Japan and the Netherlands. “We started doing some pretty crazy stuff, like chilling the water and growing arugula at 42° and 100% humidity,” Swan says. “We kind of had that eureka moment that we could grow impossible products that would otherwise not grow in Singapore, that it could be commercially viable.”

The Sustenir system is designed to work with pretty much any building. “Retrofitting an existing building, rather than building a brand new superstructure, has a far smaller carbon footprint,” Swan says. “If we’ve got these dilapidated buildings that you can’t use right now, but they can still stand for another 20 years, let’s occupy that space and see that asset all the way through.” Swan says Sustenir can convert one standard office space with a ceiling-to-slab clearance of 3 meters into an indoor farm 178 times the efficiency of an outdoor farm of the same size.

But the goal isn’t to displace outdoor agriculture. “We’re not here to grow bok choy, because that competes with local farmers,” Swan says. “We believe that the indoor farms of the future will be part of a complementary system where both indoor and outdoor farming will specifically service their community.”

How it works

By the digits

30%: Food Singapore wants to produce internally by 2030

90%: Food in Singapore currently coming from abroad

1%: Land in Singapore currently used for conventional farming

10x: Expected gains in vegetable and fish production from multi-story LED vegetable farms and recirculating aquaculture systems, according to the Singapore government

95%: Reduction in the amount of water used for indoor farming vs. outdoor

3: Operational Sustenir farms (in Singapore, Hong Kong, and Malaysia)

50,000: Square footage of Sustenir’s largest farm, in Singapore

238: Licensed farms in Singapore

Origin story

More on Benjamin Swan, Sustenir’s co-founder and CEO:

🇦🇺. He’s an Australian who has lived in Singapore for almost a decade.

🥗 He was inspired to grow fresh greens in land-scarce Singapore after trying to grow produce for his own salads. (“I’d buy a bag of [imported] lettuce and within 24 hours you could literally watch the produce melt in the bag,” Swan told Quartz. “It was just because of the time it took to get to us.”)

↕️ He researched how to adapt vertical farming’s controlled growing environment to environments, particularly in Asia, without a lot of land.

🧪 He spent months stress-testing prototypes he built himself.

🥬 He’s a big fan of kale.

🍏 His great great great grandmother invented the Granny Smith apple. (Quartz could not independently verify this, but we like the idea of multi-generational consistency.)

Put up a parking lot

Sustenir, which received a grant from Singapore’s government to expand its farming technology, is far from the only company getting in on the goals. In 2018, startup Citiponics received a permit and funding to start its first carpark rooftop farm. Using a custom-designed, modular hydroponic system, Citiponics can grow up to 25 different kinds of leafy vegetables and herbs without pesticides. According to co-founder Danielle Chan, the now 1,800-square-meter farm can grow up to four tons of food per month. It consumes about 1% of the water used in conventional farming, and 10% of the water used in other hydroponic systems.

Prices for Citiponics’ produce range from $6 for 200 grams of lettuce, to $2 for 200 grams of chye sim, a locally popular vegetable. “Instead of going to the supermarket for vegetables, now we have residents that just open their window and can see the farm,” says Chan. “They get connected to their food source.”

Quotable

“While we are trying to increase production, the net result could actually be reduced production because the traditional growers are being removed from the equation in the long term.” —Lionel Wong, founding director at Upgrown Farming Company, a consultancy that helps equip new farming business owners across Singapore

As Singapore tries to advance, its traditional farms are at risk of being displaced: Even their wealth of institutional knowledge is perceived as less high-tech. “‘30 by 30’ is really just a vision,” Wong says. “The Food Agency deserves a lot of credit in terms of what they’re trying to push, but there’s a lot of room for improvement, [as] productivity doesn’t necessarily equate to sustainability or profitability.”

Keep learning

- Three ways Singapore is designing urban farms to create food security (Quartz)

- How a parking lot roof was turned into an urban farm (Quartz)

- The indoor urban farm startup that’s undercutting importers by 30% (Quartz)

- A Singaporean farmer is building a better city greenhouse (Quartz)

- Could high-tech Netherlands-style farming feed the world? (DW.com)

- Farmers in the Netherlands are growing more food using less resources (YouTube)

- The future of farming: Japan goes vertical and moves indoors (South China Morning Post)

- Skyscraper farms are about to go global (Bloomberg)

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or companies you want to know more about.

Best wishes for a sustainable end to your week,