Poinsettias: Plant appropriation

A symbol of Xmas… and colonialism

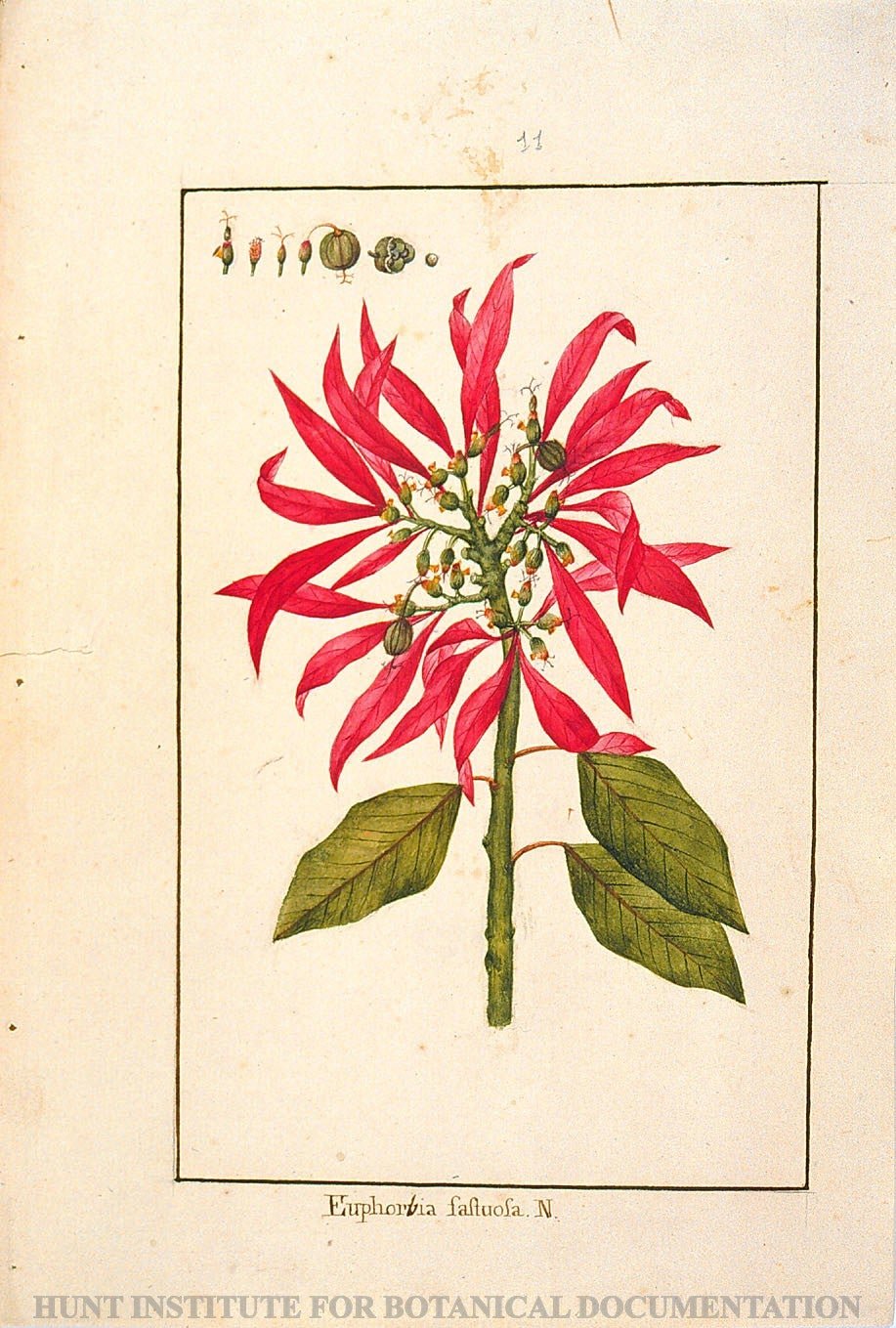

The plant we know as Poinsettia is native to Mexico and Guatemala, naturally growing in tropical forests along the Pacific coast. Its fiery bracts—they are not petals, but a type of leaf—have been coveted by powerful men for centuries. In the 1500s, Moctezuma, the last Aztec emperor, had Poinsettias transported from neighboring lands to his botanical garden in present-day Mexico City. Three centuries later, the US’s first ambassador to Mexico, Joel Poinsett, became the star-shaped plant’s namesake after shipping it to his botany-obsessed friends north of the border.

Suggested Reading

The Poinsettia has since become one of the world’s most widely grown plants and a Christmas fixture—it likes shorter days and its tiny yellow blooms show up towards the end of the year.

Related Content

As with many other commercial crops, the story of how the originally lanky, warm-weather-loving shrub became a global business is about plant engineering. It’s also a poignant tale across time and centuries of the human impulse to appropriate nature—for both status and profit.

Let’s get to the root of things.

Brief history

Before 1521: The Aztecs, who see Poinsettias as a symbol of purity, use the plant to embellish nobles’ gardens, and to make dyes and remedies to boost lactation.

Mid-1500s: After the Spanish invade Mexico, Catholic priests turn the plant into a Christmas symbol in their quest to evangelize indigenous people. As the story goes, a bunch of weeds are miraculously transformed into Poinsettias after a poor girl offers them to baby Jesus.

1804: In his tour of the Americas, Alexander von Humboldt collects Poinsettia specimens in Mexico and ships them to Europe.

1828: Poinsett, an amateur botanist and diplomat, sends the plants or seeds (it’s unclear which) to Philadelphia, where they grow in the city’s famous Bartram’s Garden.

1910: The plant begins to spread around the world. In the US, it emerges as a Christmas icon, appearing in holiday cards.

1920s: The Ecke family, whose company would eventually become the US’s top producer of Poinsettias by far, begins growing the plant in southern California.

1990s: American producers start importing cuttings from Mexico and central America instead of starting the plants in the US.

2002: The US House of Representatives declares Dec. 12 National Poinsettia Day.

2012: Ecke Ranch is sold to a Dutch company, Agribio Group.

Plant collecting’s political roots

At first glance, the Poinsettia’s early propagation might look like a friendly exchange between plant devotees interested in sharing the world’s botanical marvels. And there was some of that.

“This is no doubt how enlightenment and civilization have the greatest impact on our individual happiness… by bringing to us everything produced by nature in its various climates, and by allowing us to communicate with all the peoples of the earth,” von Humboldt wrote in his Essay on the Geography of Plants after his tour of the Americas.

But the 19th century obsession with plant collecting had broader geopolitical motives. In 1827, when Poinsett was serving as ambassador to Mexico, president John Quincy Adams ordered all US diplomats to collect rare seeds and ship them to Washington—which the US Department of Agriculture used in the following decades to jumpstart the nation’s farming industry.

The US’s ambitions went beyond agriculture. Poinsett arrived in Mexico right after it declared independence from Spain. At the time, the world’s powers were engaged in a mad scramble for Mexico’s bounty of natural resources—which they had learned about courtesy of von Humboldt’s writings. A couple of years earlier, president James Monroe had rolled out his famous namesake doctrine, warning European powers not to meddle with Latin America. The admonishment did not apply to the US, of course. Poinsett interfered heavily in Mexican politics, sowing division among local factions to sideline British interests before he was finally thrown out in 1829. His shenanigans helped steer the two countries towards the Mexican-American war.

It’s no wonder, then, that Mexico is one of the few places where the plant doesn’t go by Poinsettia…

Quotable

“Perhaps no other plant or flower we handle during Christmas week is shorter lived, wilts quicker or is more disappointing to those who receive it; yet, when the next Christmas comes around, there comes again the same demand for Poinsettias and the disappointments of a year ago are all forgotten.”

—Fritz Bahr, Fritz Bahr’s Commercial Floriculture, 1922

By the digits

10 to 12 in: Height of most popular potted Poinsettias sold in the US

100+: Poinsettia varieties

90%: Share among the 100 varieties of Poinsettia grown in Mexico that are red (white and pink make up the other 10%)

2.2 million: Number of Poinsettia plants imported to the US in 2022

$11.5 million: Value of Poinsettia plant imports to the US

$157 million: US sales of potted Poinsettias in 2020

31%: California’s share of potted Poinsettia sales in 2020

2 to 3: Months Poinsettias can survive if properly cared for

$3-$12.99: Range of advertised prices for six-inch-pot Poinsettias across the US

Pop quiz

Which of these is not a Poinsettia variety?

A. Hawaiian punch

B. Orange spice

C. Viking red

D. Pink cadillac

Parlez-vous Poinsettia?

👞 Cuetlaxóchitl: Poinsettia’s name in náhuatl, the Aztecs’ language, which means leather flower or flower that wilts.

👶 Nochebuena: Today, Mexicans call the plant Christmas Eve.

⭐ Étoile de Noël: The French refer to it as a Christmas star...

🐰 Flor de Pascua: …and in Spain it’s known as Easter flower.

🦞 Lobster flower: Another English alias, because of its color.

🔬 Euphorbia pulcherrima: The scientific name of Poinsettia, which deems it the “most beautiful” in its family.

Watch this

This video from Clemson Extension explains everything you want to know about the plant, including its history, how it’s bred, and how to make it last. Impress (see also: annoy) your relatives with your plant knowledge this season.

Poll

Which plant wins Christmas?

A. Poinsettia

B. Christmas tree

💬 Let’s talk!

It wasn’t just cake that was fake last week for our obsession on trompe l’oeil, our poll was too... or at least it was gobbled up so we don’t have the results to offer anymore. Please accept this 🧁 as a token of our apologies.

Today’s email was written by Ana Campoy (who wishes she could grow Poinsettias year round), edited by Susan Howson (who only cares about kudzu), and produced by Morgan Haefner (who can’t keep plants alive).

The correct answer to the pop quiz is A., Hawaiian punch. Hawaii’s climate makes it a great place to grow Poinsettias on the ground, but alas, there is no “Hawaiian punch” variety—yet. There is, however, one called “ice punch.”