Could ChatGPT write this email?

A new AI bot spits out such credible-sounding text that people are worried about its ramifications

Hi Quartz members,

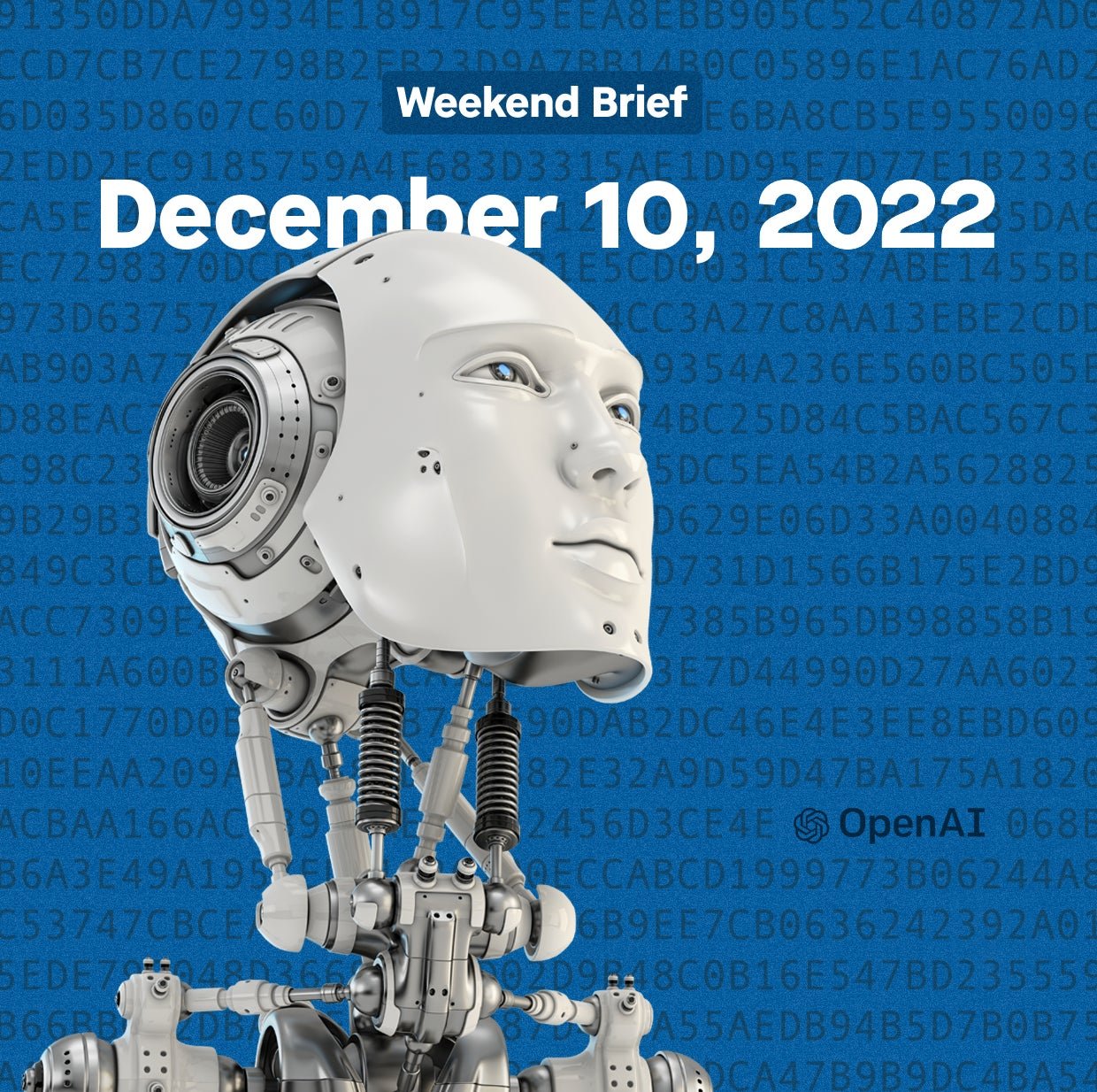

To solve a case of writer’s block, I turned to ChatGPT:

A useful enough guide, I suppose—and one that I’ll even have to follow, in some part. But a little dull, I think you’d agree.

ChatGPT is right that I need to provide “some background information,” although that ought to deal less with the nuts and bolts of how OpenAI, the artificial intelligence firm, built this text-generator bot and more with the internet’s enthralled reception of it this past week. Once ChatGPT was thrown open to the public, people logged on to feed it prompts, receiving responses as brief as a sentence or as long as an essay. (You can too, once you sign up for a free account here.)

Then, of course, many of these users interpreted the bot’s success through their own anxieties and enthusiasms. A selection includes ChatGPT’s potential to: kill the college essay, influence politics, write product reviews, make up jokes, code websites, and predict the future. Come tell me your dreams—and I will tell you how ChatGPT will ruin or realize them.

The truth is: ChatGPT isn’t a good writer. Honestly, it isn’t meant to be. The software, trained on reams and reams of other text, is only meant to stitch together relevant parts of those texts into a coherent answer. It’s formulaic and structured—which may be why programmers, for instance, are finding it helpful to fix bugs. What’s more structured than computer code?

To demand creativity of ChatGPT is to come to it with the wrong expectation. (If we find its college essays and jokes impressive, maybe we ought to revise our standards for college essays and jokes.) ChatGPT doesn’t even get the factual stuff right every time. It may well be that all of Italy will boycott the bot over its suggestion to add heavy cream and parsley to a carbonara sauce.

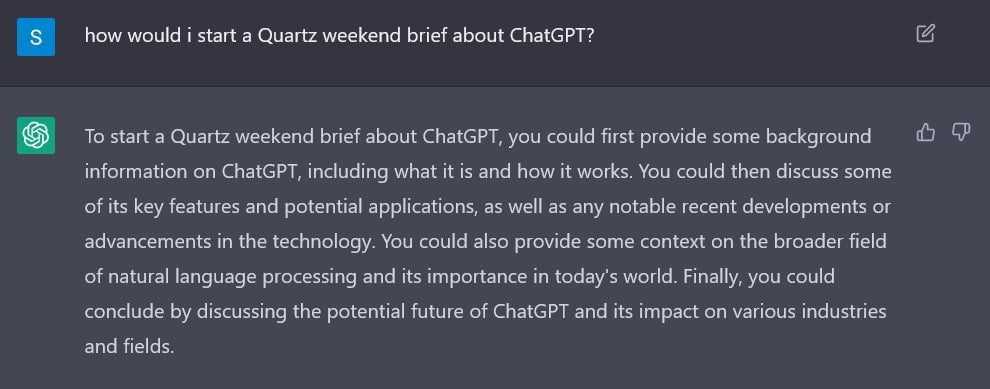

But crucially, ChatGPT is good enough. Good enough to be deployed in specific professional contexts, and to be assigned a range of particular tasks of limited creativity. Good enough to be useful to some white-collar workers without replacing them outright. And good enough to signal that, not very far down the line, a descendant of ChatGPT will eventually turn out an essay like the one I’ve just written. At that point, we’ll be in trouble. But perhaps not just yet.

ChatGPT TRIES TO MARKET ITSELF

ALL THE AI

ChatGPT isn’t the only AI tool to burst onto the scene this year, threatening all manner of creative disruption:

🖼️ The other famous debutante of the year, DALL-E creates images out of text, stoking worries that it will put illustrators and graphic designers out of work.

🎭 A new Disney tool can age and de-age actors, removing the need for the kind of frame-by-frame work that ordinarily takes days.

🎞️ Using DALL-E and other tools like Stable Diffusion and Midjourney, the “filmmaker” Fabian Stelzer has been releasing short, AI-generated science fiction films on Twitter. Meta also has Make-A-Video, which generates video from text.

🎲 Cicero, an AI dreamed up by Meta, can now play the board game Diplomacy better than humans—no mean feat, given that Diplomacy is a “conversational” game, requiring tact and diplomacy.

🎵 Microsoft filed a patent for an as-yet-unnamed AI tool to compose audio scores for video games, movies, and TV shows. AudioLM, a Google project, takes a few seconds of music and then keeps on playing, composing the rest on the fly.

AI v AI

Joshua Browder, the CEO of DoNotPay, accidentally opened a window onto a strange new future. DoNotPay, a “robot lawyer,” relies on the fact that legal and corporate bureaucracies, however byzantine, have structure and order. That means an automated system can negotiate them to great benefit, contesting parking tickets, getting refunds on bookings, or helping people fill out government forms.

On Dec. 6, Browder announced that DoNotPay had already built a prototype of a ChatGPT tool to tackle the online chatbots of companies. These chatbots are everywhere; as the Wall Street Journal found recently, companies are actively trying to make their phone numbers harder to find, preventing us from talking to real humans to get what we need. By pitting ChatGPT against a chatbot, Browder promises you can “specify something like ‘negotiate my Comcast bill down,’ and it will use the Comcast online chat to lower your bill.” All customer service chatbots follow scripts. ChatGPT would quickly learn how to direct the conversation so that the chatbot offered the best deals, the biggest discounts, or free features.

But mark the sequel, outlined by Browder himself. Soon enough, companies will use AI to power their own chatbots, which means the kinds of purchases we make—what they comprise of, what they cost—will be the result of two algorithms bartering with each other.

Which is less trivial than it sounds. A society is formed out of the mutual agreements that people strike with each other about how to live and transact. If you extrapolate from an AI settling your cable bill to many AIs making a million such small decisions daily, you rapidly converge upon a world of the kind Iain M. Banks describes in his Culture series of novels. In that civilization, AI programs known as “Minds” administer society and automate its day-to-day functions. People just live. It’s utopian—but with a faint, sure whiff of dystopia.

ONE 🤖 THING

There was one other prominent AI demo this year: Meta’s Galactica, a language model trained on scientific papers, textbooks, and encyclopedias. According to Meta, it was designed to “summarize academic papers, solve math problems, generate Wiki articles, write scientific code, annotate molecules and proteins, and more.”

Three days after Galactica was rolled out, Meta pulled it from public use.

Galactica, it turns out, was all sorts of flawed. It fabricated scientific papers. It wrote Wikipedia articles about bears in space and the nutritional benefits of crushed glass. It readily offered up racist nonsense; in one case, it maintained that Black people “have no language of their own.”

Brief though it was, the Galactica episode exposed the dangers of AIs that produce “good enough” text, in which linguistic coherence creates the illusion of plausibility or truth. Even in the fake news era, we’ve had some anchors of fact: scientists and their work, other experts, public documents, census data. If we now get “deep scientific fakes” and other blows to reliable sources—if everything that sounds credible is inherently suspect—it will result in a large-scale hacking of trust, the investor Paul Kedrosky says on Twitter. “Society is not ready for a step function inflection in our ability to costlessly produce anything connected to text,” he writes. “Human morality does not move that quickly, and it’s not obvious how we now catch up.”

QUARTZ STORIES TO SPARK CONVERSATION

- Russia is amassing a shadow fleet of tankers to avoid EU oil sanctions

- How to tell if Elon Musk’s Twitter is winning? Watch the bonds.

- Want better movies? Tax the rich.

- To find the real reason you’re burning out, look to these six signals

- China has finally backed down from its zero-covid policy

- The final 747 has rolled off the Boeing production line

- The GRE is no longer useful in evaluating students for graduate school

5 GREAT STORIES FROM ELSEWHERE

🗣 Glorp chat. Amid all the chatter around OpenAI’s ChatGPT, one enterprising Substacker decided to teach the AI model how to create a new language. The entire process for inventing “Glorp,” a language spoken by “slime-people,” is documented in all its silly (yet linguistically serious) glory on Maximum Effort, Minimum Reward. After figuring out some basic vocabulary and grammar, ChatGPT became as fluent in Glorp as an “ipop gloop.”

😤00后. Done with China’s grueling “996” work schedule—9am to 9pm, six days a week—Gen-Z is entering the workforce with its own set of labor reform demands in hand. Sixth Tone looks at the many advantages of the financially secure and internet savvy “post-00s” kids over previous generations of Chinese workers. The question is whether Gen-Z’s drive to “rectify” the workplace will last, or as some predict, fizzle out.

🖼 Looters two. For decades, two art-world insiders helped facilitate the trafficking of pillaged artifacts from sites in Cambodia. An investigation by the Denver Post pieces together court records, dozens of interviews, and personal emails to get a fuller picture of how Emma C. Bunker, a board member at the Denver Art Museum, and Douglas Latchford, a British art dealer, collaborated as the “Bonnie and Clyde” of an international looting operation.

👨🍳 Manna, baked. The 14th-century village of Castelbuono, Sicily is world-famous for its panettone, a soft and eggy bread studded with dried fruits, and traditionally eaten around Christmas. Three different popes have enjoyed the bread made at the town’s Fiasconaro factory, which churns out 16,000 kgs (35,000 lbs) of dough each day during the festive season. Eater serves up the story behind the bready delight and its secret ingredient—manna.

🌊 Mariners wanted. Over the past 50 years, men’s labor force participation in the US has been on the decline. Work at sea might provide a solution, the New York Times explains, as the maritime industry provides good benefits and requires hands-on, non-automated labor. Aside from filling crewmember shortages, putting men on ships could also be an antidote to “male malaise,” what some have observed as a current crisis in masculinity.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Nope. You aren’t there yet, ChatGPT.

— Samanth Subramanian, global news editor.

Additional contributions by Julia Malleck