Like a lead zeppelin

A Hindenburg Research report has tanked the net worth of Gautam Adani, Asia's richest man as of just last week

Hi Quartz members!

Allow us to introduce you to the world’s most expensive Twitter thread.

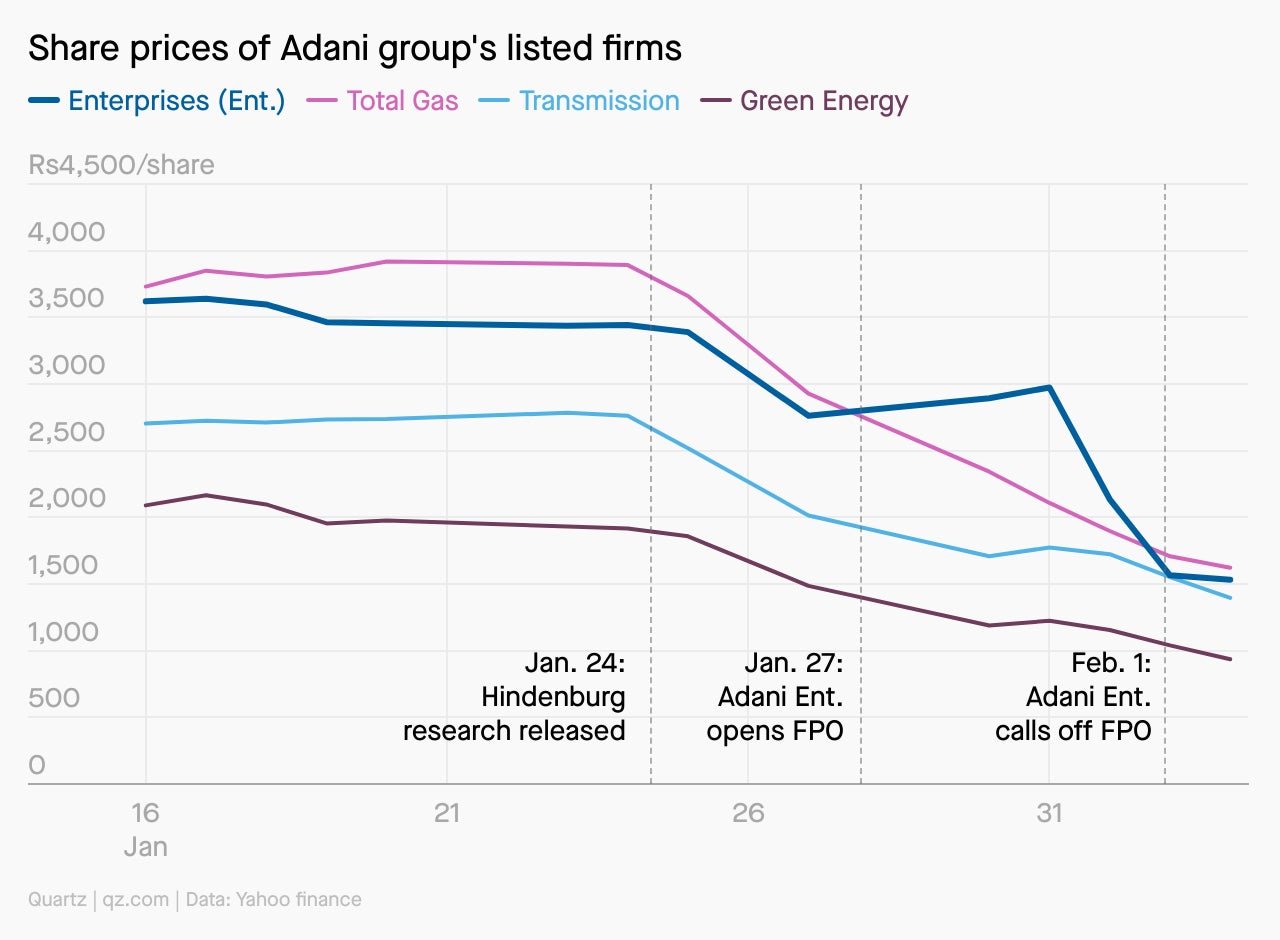

Within six days, this thread—and the withering report behind it, both courtesy of a New York short-seller called Hindenburg Research—erased $58 billion from the net worth of the Indian titan Gautam Adani. Within ten days, Hindenburg’s revelations of stock manipulation and accounting fraud wiped out $112 billion from Adani’s listed companies, half their market value. Adani had to cancel an FPO (a share sale via a follow-on public offer). As of writing, the bleeding hasn’t been stanched.

Some short-sales come as a surprise; Hindenburg’s, though, confirmed the suspicions many Indians harbored against Adani. This much was known: His rapid success has been driven by deep debt and his connections to the ruling government (on which below). But if Hindenburg’s five-person research team could uncover evidence of fraud and manipulation, Indians must ask: Why have the country’s own business media or regulators pinned nothing as significant on Adani’s conglomerate? Why, for instance, has the Securities and Exchange Board of India concluded nothing after a year and a half of investigating Adani’s offshore funds? And why were bans imposed on Adani companies for stock manipulation later reduced to fines?

The answers to these questions say less about Hindenburg than they do about India. About the legal loopholes permitting shell companies in Mauritius, which launder money and manipulate Indian stocks. Or about the trillions of rupees in bad loans that state-owned banks have had to write off over the past five years. (“Groups that are perceived as politically connected can still tap the banks for loans,” Hemindra Hazari, a Mumbai-based banking analyst, told the Financial Times. “If you are any other highly stressed group, then it is difficult for you.”) Or about the lethargic, often-politicized pace of regulators and investigators.

In 2021, India placed 7th on the Economist’s crony-capitalism index, up from 9th place in 2016. India’s share of billionaire wealth derived from “crony sectors”—those dependent on the state’s licenses and contracts—rose from 29% to 43%. Adani has benefited most egregiously from this phenomenon, but he is far from the only one.

THE BACKGROUND

Gautam Adani hails from the same state as prime minister Narendra Modi: Gujarat, in western India, known for its class of merchants and entrepreneurs. His ventures into infrastructure began with ports and power transmission in the 1990s, but his star soared after he began publicly backing Modi, then Gujarat’s chief minister, in the early 2000s. (Adani has denied that he owes his rise to Modi.) Many Indians outside Gujarat, though, would have first seen Adani’s face in an undated photograph, showing Modi lounging aboard the billionaire’s jet. During his prime ministerial campaign in 2014, Modi used Adani’s planes to traverse the country.

Over the last decade or so, Adani’s companies have stuck their fingers into practically all the pies in the Indian pie shop: aviation, shipping, coal and gas, mining, green energy, infrastructure, news television. Their valuations made Adani a wealthy man. Last September, for one glimmering moment, Adani was worth $155 billion; only Elon Musk was richer.

But Adani’s companies were known to be built on debt, to the point that they were deeply overleveraged. And they’d grown in such neat lockstep with the advent of the Modi government that murmurs of “crony capitalism” were unavoidable. Adani kept winning government contracts, state-run banks lent him billions of dollars, and a public-sector insurance firm bought shares in his companies, bidding up their value.

It looked as if nothing could shake the empire. Then, the Hindenburg Report’s gale-force winds blew in.

$44 billion: The price of Twitter, for Elon Musk

$3.7 billion: Pakistan’s remaining foreign-exchange reserves, as of Feb. 1

10: The number of Adani companies listed on Indian exchanges

38: The number of shell companies in Mauritius controlled by Adani’s brother Vinod, and by other associates

23,000: The number of employees in Adani’s conglomerate

156: The number of subsidiaries under Adani Enterprises, the flagship company

11: The number of employees in the firm that audits Adani Enterprises

5: The number of full-time employees at Hindenburg Research, as of 2021

CRYSTAL BALL

What lies ahead for Adani?

On the evidence at hand, it’s difficult to believe that his companies will collapse entirely. They own or operate assets of value, such as ports and power grids. And there has been no signal, as yet, of defaulting on any large-scale infrastructure projects that the companies are executing. The rout on the equities market could be read as just that: a correction, and a chastening.

But Hindenburg has also opened a window for banks and regulators to reassess their relationship with the conglomerate. Credit Suisse and Citigroup will no longer take Adani bonds as collateral for margin loans, Bloomberg reported. India’s market regulator is reviewing some of Hindenburg’s allegations, as is Australia’s Securities & Investments Commission. Raising money will become more difficult, Moody’s said, after the heated sell-off in Adani stocks and the canceled share sale. For Adani, the swagger of being Asia’s—or even India’s—richest person has evaporated. Troubles with fundraising and the law will make it much harder for him to regain that title.

EAT MY SHORTS

For champions of the practice, the Adani case presents a shining defense of short-selling. To root out inefficiencies and fraud in the market, they’d say, short-sellers are vital. Plus, it should be as legitimate to bet against a security as it is to bet for it. The argument is harder to make when the pain of the ensuing crash spreads far beyond. In 1992, when George Soros shorted the pound, making $1 billion in a month, the currency’s devaluation hit every Briton, and the Exchequer lost nearly $8 billion in today’s money.

Compared to Soros’s time, short-sellers have more to do than just research and invest. Hindenburg’s task was not just to find the cracks in Adani’s companies but to publicize them as widely as possible, in part to convince retail investors (on Twitter and elsewhere) to get rid of their Adani shares as well. The marketing of the short sell may not always work, but it turns the exercise into even more of a self-fulfilling prophecy. Having taken the bet, short-sellers are in a tearing hurry to make it come true.

QUARTZ STORIES TO SPARK CONVERSATION

- Why the US labor market seems to be unbreakable

- Netflix accidentally revealed its blueprint to stop password sharing

- Three pay principles to be an antiracist company

- UC Berkeley is starting a business school course on managing unionized workplaces

- Here’s why a BlackRock portfolio manager says you should buy chickens

- Elon Musk killed the good bots

- How to keep ESG moving ahead in the face of political madness

5 GREAT STORIES FROM ELSEWHERE

🌀 Seneca’s dilemma. Smartphones may have condemned our brains to perpetual distraction, but the problem of a scattered mind is nothing new. Even Seneca the Younger, in the 1st century CE, despaired over the diversions of too many books. Looking across thousands of years, an essay from Aeon shows that thinkers have long fretted over shrinking attention spans, especially in the face of new technology.

🦾 Out on a limb. A cyborg future is closer than you think. Tetraplegics, people who are paralyzed from the neck down, are already trailblazing the use of brain-controlled prosthetics. One day, that kind of technology could be used to augment human capacity across professions and regardless of physical ability. IEEE Spectrum explains how the brain’s neural signals could be tapped to unlock the use of extra robotic limbs.

🐮 Food footprint. Calling all grocery aisle deliberators: If you’re wondering whether barley or millet is better for the environment, we’ve found help. The Washington Post has a tool that compares the footprint of dozens of different products on a per-calorie basis. Illuminating as the tool may be, it also shows the complexity of a climate scorecard, and how low-impact foods can still exact high ecological damage.

💩 A shitty situation. Social media has become nigh unscrollable these days, and “enshittification” may be to blame. A piece from Wired lays out a theory of the platform life-death cycle, and explains how tech monopolies are destroying user experience to claw more money from both consumers and advertisers. If it’s any consolation, the sites may also be digging their own graves.

😤 Bosses are back. In a boy-band comeback that nobody asked for, the bosses are returning to the office and making it clear that they wear the pants. Zuckerberg himself dubbed 2023 the “year of efficiency,” and as headcounts roll, it’s no wonder that workplace power is seeing a rebalance.The Wall Street Journal discusses the triumphant return of corporate executives as the labor market softens and workers are jolted from pandemic-era flexibility.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Don’t sell yourself short this weekend,

—Niharika Sharma, reporter; Samanth Subramanian, global news editor.

Additional contributions by Julia Malleck and Amanda Shendruk