The Japanese paradox

Japan's Nikkei index hit a record high—even as the country slipped into a recession

Hi, Quartz members!

Suggested Reading

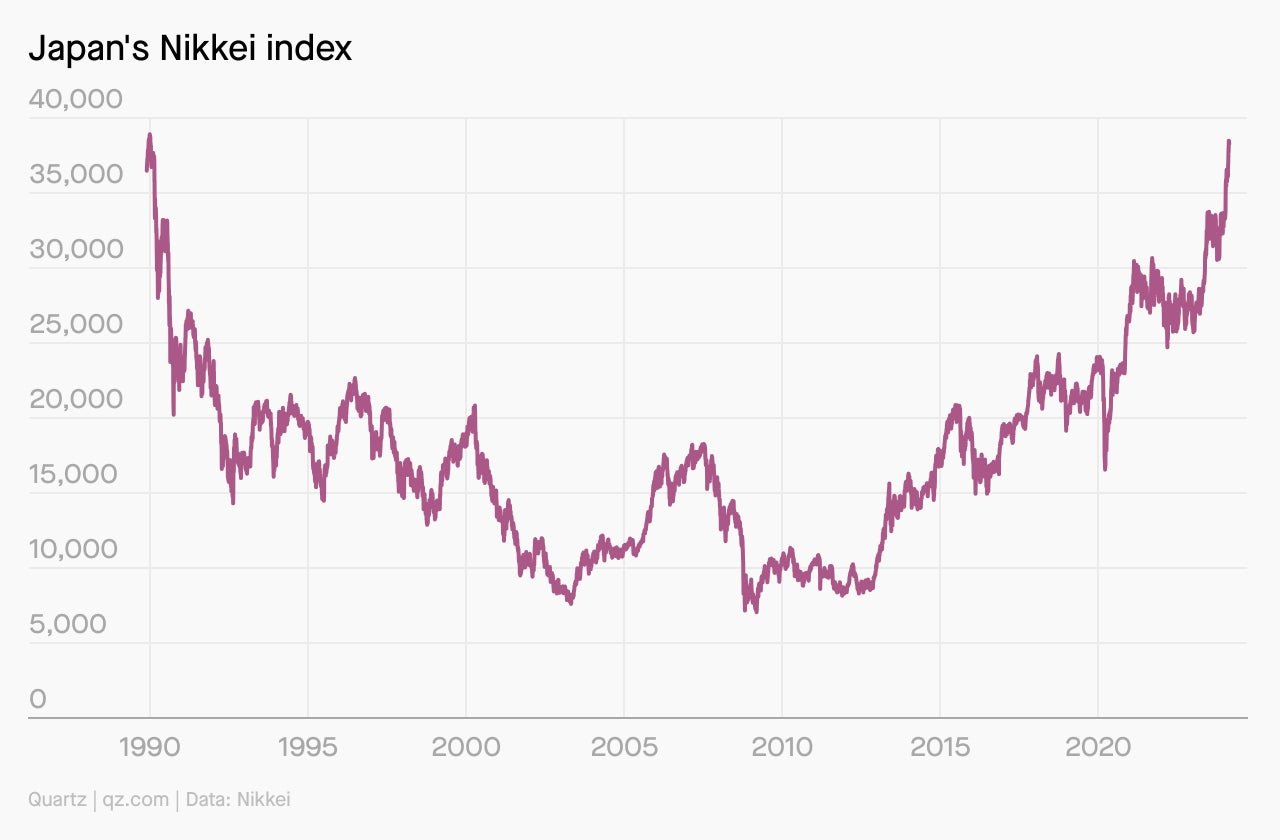

On the very last day of trading in 1989, the Nikkei, the Japanese stock index, peaked, closing at 38,915.87. Then the festivities ended. Over the next three-and-a-bit decades, the index fell and fell and fell, losing over 80%. A long spell of deflation depressed wages and economic growth. The 1993 movie Rising Sun (not even enjoyably pulpy), about corporate intrigue between Japanese and American firms, was perhaps the last flicker of the 1980s, when Japan was the economy to beat.

Related Content

The 1989 peak seemed inescapable in two ways. First, it felt like an “iron coffin lid,” as traders in Tokyo called it: a ceiling past which the Nikkei would never ascend. Second, it was a drag on any other kind of progress that the Japanese economy achieved—a sobering reminder of the market that was.

This past week, the long lethargy came to an end—at least as far as the Nikkei is concerned. On Thursday, the index hit an intraday trading high of 39,029, surpassing its 1989 high-water mark and setting a new all-time record. On the floor of Nomura, the Japanese brokerage firm, traders broke into cheers and applause when the new record flashed just before lunchtime.

In a way, the record is just that: digits unto themselves, not necessarily reflective of the economy that produced it. It has barely been a week, for instance, since Japan officially announced a recession, after its economy shrank for a second successive quarter. Around the same time, Germany surpassed Japan as the world’s third-biggest economy. The yen has been falling consistently against the dollar—in part because the Bank of Japan has been maintaining negative interest rates in an effort to fight deflation.

All of which prompts the question: What’s happening with the Japanese economy?

CHARTED

THE NIKKEI BOOM

In a way, the recent surge in the Nikkei is similar to the buoyancy of the S&P 500. Both have been driven by the soaring fortunes of tech companies. (It is no coincidence that the Nikkei record was set hours after Nvidia announced fourth-quarter earnings of $22 billion, up 270% from the previous year.) Six out of the top 10 Japanese firms by market capitalization are now tech companies. (This is a structural shift; back in 1989, the top 10 included six banks.) The excitement around AI and Nvidia, for instance, turned Tokyo Electron, which makes chipmaking equipment, into Japan’s third-most valuable firm.

In parallel, though, Japanese corporate governance has been undergoing a vital decade of reform. Last year, for instance, the Tokyo Exchange Group introduced a new rule that compelled listed companies to explain if and why they are not using their capital efficiently. (Companies that fail to do so could be delisted as early as 2026.) Listed corporations must also offer more disclosure about subsidiaries or equity affiliants. The declared aim of these reforms is to boost transparency and shareholder returns. A focus on margins and balance sheets has tripled corporate earnings since the heady days of the 1989 bubble.

All of this, added up, amounts to a siren song for foreign institutional investors. In the fiscal year 2014, foreign investors bought $20.2 bilion worth of Japanese stocks. By contrast, in one January week alone, foreigners bought $2.68 billion in Japanese equities.

AND YET...

...there’s a recession in Japan. And behind that lies a different, but linked, story.

After all those years of deflation, the Japanese economy is bearing the unfamiliar pain of inflation—even though, by global standards, it’s moderate. (Last December, Japan reported an inflation rate of 2.6%, not very far off the global consensus target of 2%.) Companies are passing price increases on to consumers, which does wonders for corporate bottom lines but cramps spending, especially when wages haven’t kept up with inflation.

This presents Japan’s central bank with a dilemma. Almost as a muscle memory from the long deflationary spell, the Bank of Japan has persistently kept interest rates low to goose spending. Now that inflation has ticked up, it will be tempted to start hiking rates. But the fallout of that might include a further constriction of spending, prolonging the recession—especially if companies continue to hold wages at their current level. On the other hand, continuing with low rates will allow inflation to creep up. It will also weaken the yen further. That’s great for Japanese exporters like Toyota, and also for foreign investors into the Nikkei and other indices, but not so much for people who face higher prices for imported products.

ONE 🇨🇳 THING

Among the reasons for the rise of the Nikkei is the money that’s leaving Chinese indices and looking for investments in other big markets outside the US. China’s benchmark CSI 300 index declined more than 11% last year, even in the middle of rallies elsewhere. Worried about this rout, Beijing recently replaced its top securities regulator. Meanwhile, in the first three weeks of 2024, foreign investors (including those from China) bought $10.1 billion more in Japanese equities than they sold during the same period. In a Bank of America Merrill Lynch survey, nearly 30% of asset managers said they expected Japanese stocks to yield returns of more than 10% over the coming year. They may be wrong—but as economists know, heady optimism and dire pessimism are both self-realizing mechanisms. If investors are overwhelmingly bullish on Japan and bearish on China, and if they show it with their money, their beliefs might well come true—at least in the short term.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Have a record-enjoyable weekend,

— Samanth Subramanian, Weekend Brief editor