The zone of interest

The Fed's high interest rates are biting everyone: banks, the US government, and regular Americans

Hi, Quartz members!

Suggested Reading

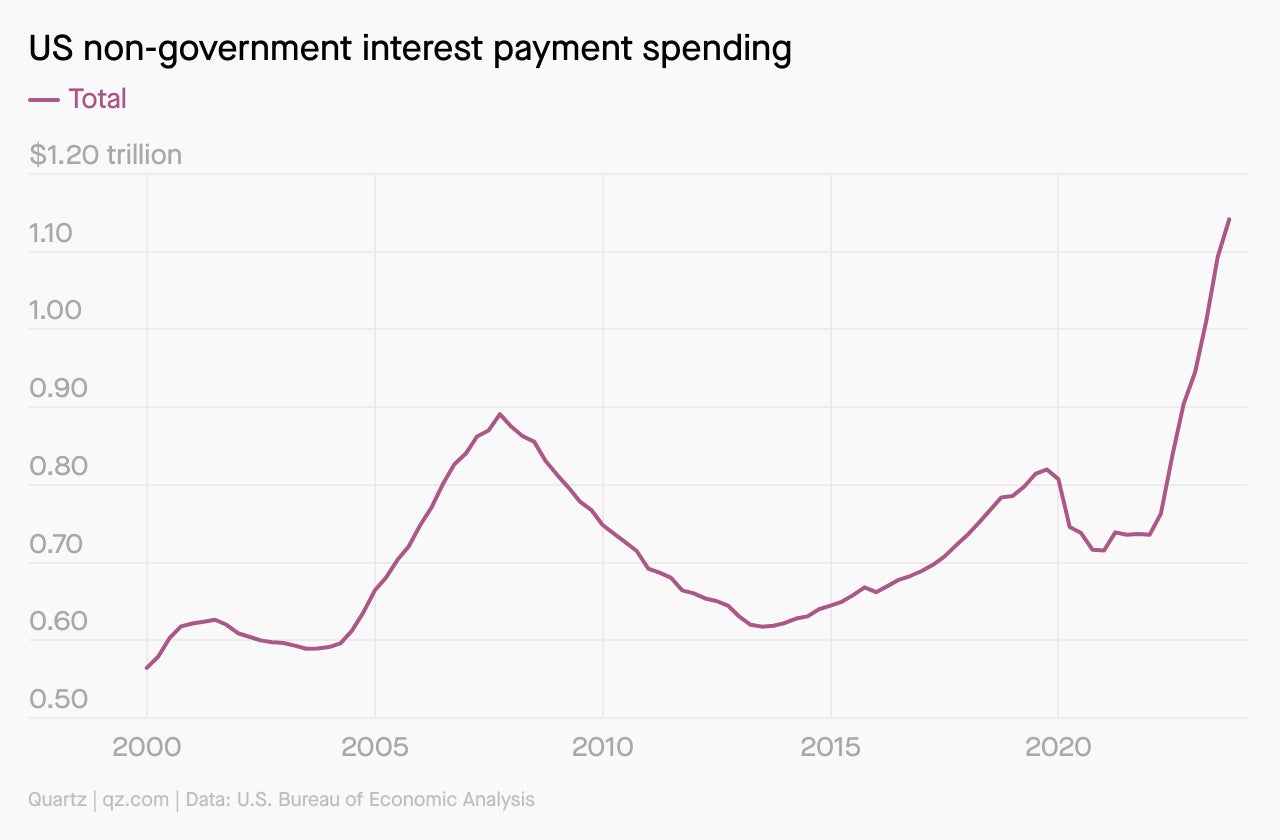

Sometimes one big number says it all. Here’s that number: $1.1 trillion.

Related Content

That’s how much Americans spent on interest payments in the last quarter. And for the first time since at least 2000, nearly half of those payments were not made towards mortgages. “It’s not that there has been a sudden decrease in mortgage interest spending,” as Quartz’s Melvin Backman points out, “it’s that higher rates from the Federal Reserve are hitting so many other categories so hard at the same time.”

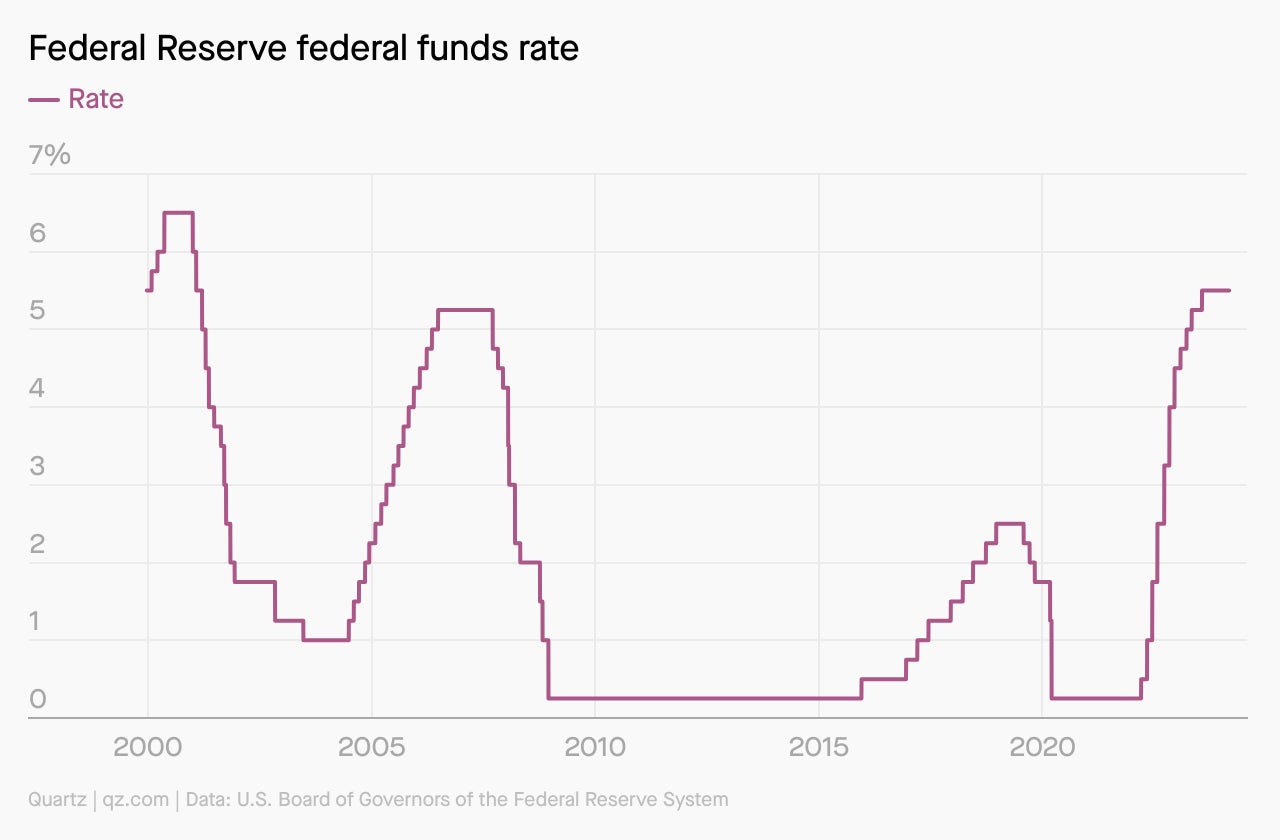

This was inevitable—a direct result of the Federal Reserve hiking interest rates to fight inflation, and keeping them elevated for months on end. Through the buoyancy of 2023, perhaps best epitomized by the 24% rally in the S&P 500, the specter of high rates lurked, always threatening to throw cold water on the party. Rate increases take their own time to affect the economy, as analysts pointed out. The pain shows up with a lag, but it definitely shows up.

American consumers aren’t the only ones feeling that pain now. The struggles of New York Community Bank, for instance, are attributable in part to interest rates as well, because investors want to sell its paper to buy debt with higher rates instead. Small businesses, less resilient to financial pressures, face escalating payments on their loans. The federal government’s interest payments will hit $870 billion this year, according to the Congressional Budget Office (pdf)—higher even than the defense spending bill, perhaps for the first time in history.

The question for economists now is: When will this prove too much for American consumers, to the point that they stop spending enough to stall the economy? For now, at least, it looks like that point has yet to arrive. Consumer sentiment improved in January and then again in February, and is 19% higher compared to a year ago, according to the University of Michigan’s consumer surveys.

And even if people are borrowing more, their debt payments still formed less than 10% of their disposable income, as of the third quarter of 2023. This is significantly less than the peak during the financial crisis, when the proportion hit 13%. Which means that big number—$1.1 trillion—may rise still further before we see it dip.

CHARTED

ALL EYES ON THE FED

Every American who is burdened with higher interest payments—which, given that taxpayers foot the bill of the US government’s payments, technically means every American—is now watching the Fed closely to see when it will start cutting rates. That’s likely to happen this year, but no one seems to know exactly when.

For a while, the expectation was that the first rate cut would come in March. But as inflation stayed relatively elevated, Jerome Powell, the Fed chair, said at the end of January that a March timeline was unlikely. Goldman Sachs expects four rate cuts of 25 basis points apiece, with the first cut coming in June. (It had to temper its earlier expectations: five cuts, starting in May.) There is still a risk that the first cut could come later than June, according to economists surveyed by Reuters. This past week, Powell said the Fed won’t make a move “until it has gained greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward” its 2% target. As of the last measure, annual inflation stood at 2.4% and the core yearly measure at 2.8%.

ONE 💲 THING

It’s true that the Biden government may not last beyond this year, but if it does, it will find that high interest rates are handicapping one of its pet priorities: green energy. New renewable energy plants are highly capital intensive, and if the cost of capital remains high, investors will be less able, or less willing, to pay out.

Last November, two large offshore wind projects in New Jersey were canceled in large part because of high rates. Together, they would have made up nearly a fifth of the government’s offshore wind power target for 2023. According to one analysis, the cost of a new solar farm or an offshore wind project could rise by a third if rates rise from 3% to 7%. It’s true that renewables remain broadly competitive with fossil fuels even after such surges in expenditure. But on the margin, new projects could flounder or collapse. That’s a problem, because right now, the planet needs all the renewable energy it can get.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Have a weekend full of only the best kind of interest,

— Samanth Subramanian, Weekend Brief editor