The politics of bitcoin

As bitcoin rises and rises, crypto firms are pouring money into election campaigns

Hi, Quartz members!

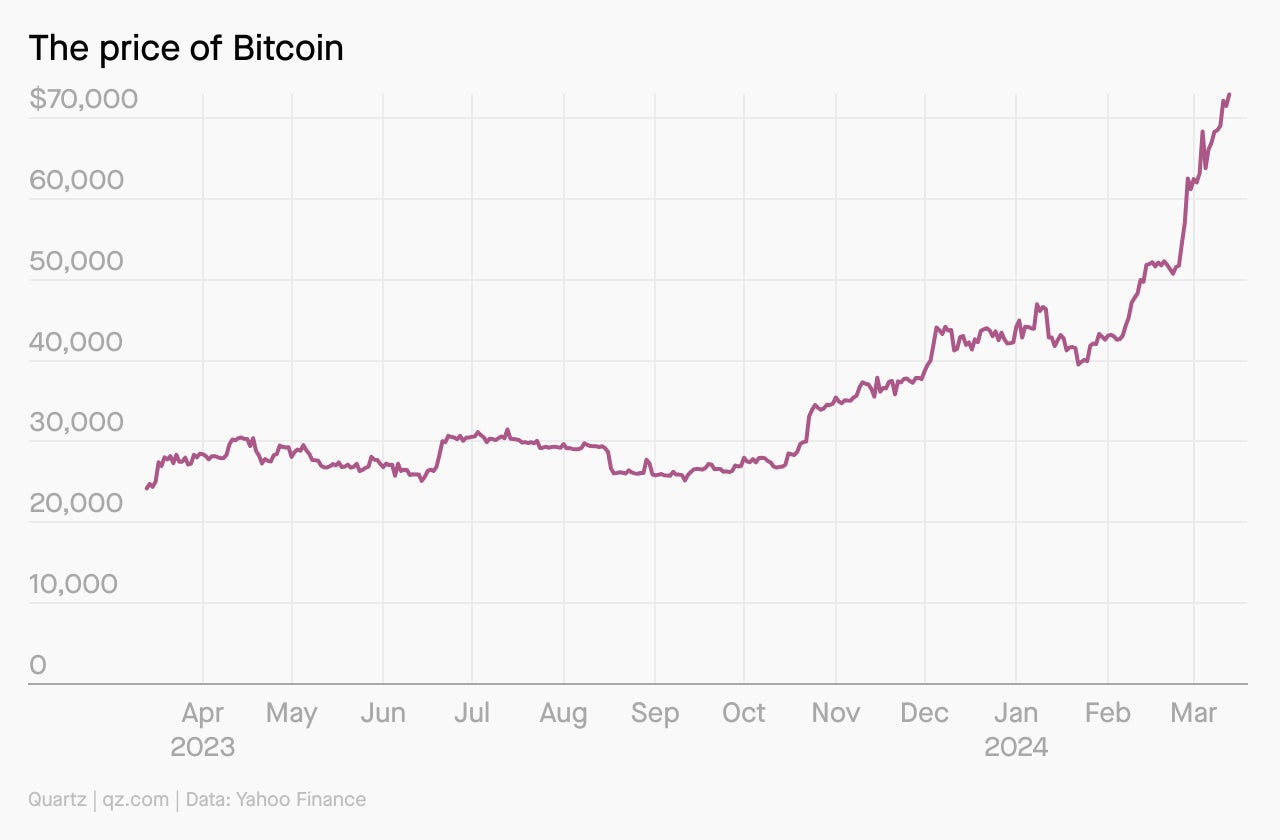

As the value of bitcoin has rebounded over the past year, crossing $73,000 this past week, another entity has found new wind in its sails: the crypto PAC.

And it isn’t just one PAC, or political action committee. The crypto industry has a number of them, with an aggregate of at least $85 million in funds. One of the biggest such PACs, Fairshake, defines its mission on its sparse website thus: to support candidates who will provide “blockchain innovators the ability to develop their networks under a clearer regulatory and legal framework.” Crypto skeptics, in other words, won’t see a red cent of this money.

The PACs are already having an effect on U.S. elections. On Super Tuesday, earlier this month, Rep. Katie Porter came third in a California Senate race, after three PACs spent $10 million campaigning against her. She was one of the legislators who signed a letter (pdf) asking about the energy use and environmental impact of bitcoin mining operations. (She might have read Quartz’s classic explainer, “How much energy does bitcoin use?”) Among the backers of these three anti-Porter PACs was Coinbase, the crypto exchange that, naturally, relies too much on bitcoin to disregard legislators who wish to constrain its mining on environmental grounds. As bitcoin has surged, so has Coinbase’s stock — and its ability to pay into PACs. The company has contributed at least $23 million to crypto PACs.

Other candidates have received a crypto boost instead of a crypto ding. Crypto PACs spent $1.7 million to back Shomari Figures, who ran in a House primary in Alabama, and $1 million on Julie Johnson, who fought a primary to represent Texas in Congress. Both of them came out on top. Both of them are also overt champions of crypto.

Porter didn’t necessarily lose just because the crypto PACs attacked her; for one thing, her Democrat colleague Adam Schiff, who placed ahead of her, was better known and had outspent her. But she seemed to think of the rise of these PACs as a malevolent new force in US politics — as “dark money” and “rigging,” even. US politics already has plenty of malevolent old forces to contend with. Is Porter right about the crypto PACs?

CHARTED

QUOTED

“Rigged” means manipulated by dishonest means. A few billionaires spent $10 million+ on attack ads on me, including an ad rated “false” by an independent fact checker. That is dishonest means to manipulate an outcome. I said “rigged by billionaires” and our politics are—in fact—manipulated by big dark money. Defending democracy means calling that out.

— Rep. Katie Porter, in a statement posted on X

WHAT DOES CRYPTO WANT?

On Julie Johnson’s campaign website, she lists her political priorities. They include the establishment of “clear rules of the road for the crypto industry to build technology that benefits everyday Americans, while protecting consumers and ensuring equitable outcomes for all.” Broadly, this is what the industry wants as a political outcome: regulation. As Kara Calvert, the head of US policy at Coinbase, told the New York Times: policymakers “have to make some decision: Do they want to be for clear rules and consumer protections? Or do they not?”

Admittedly, this is an unusual ambition for political bankrollers; usually industries are pressing for less regulation, or at least different regulation. But crypto is an unusual industry. It seeks greater legitimacy in the eyes of government agencies. More regulation will lend it that legitimacy, but it can also preempt officials like Sen. Sherrod Brown or the SEC head Gary Gensler from implementing tighter constraints upon an industry they regard warily.

To be sure, crypto PACs will also want a particular kind of regulation to suit their needs. But in funding campaigns as a means of lobbying for such rules, they are no different from hundreds of other companies and industry bodies that do the same thing. (Supporters of the super PAC system contend that it is transparent by law, although there are ways of hiding where money comes from: by channeling it through “nonprofits” with milquetoast names, for one.)

Porter’s argument that her particular election was “rigged” is a weak one. Every major American election, in fact, is influenced by donations from entities keen to get prospective legislators and officials on their side. It is an inescapable fact today that an electoral run requires millions, or tens of millions, or hundreds of millions of dollars — depending on the prestige of the office sought — to conduct. The crypto industry is merely joining the mainstream.

ONE 💰 THING

Critics of crypto PACs point to Sam Bankman-Fried as the most flagrant cause for concern. Last year, an indictment accused SBF, the disgraced founder of the crypto exchange FTX, of using stolen customer funds to donate more than $100 million to campaigns in the 2022 midterm elections. (SBF was convicted last November on seven counts, including wire fraud and conspiracy, and prosecutors have said that a second trial on campaign finance violations may not be necessary.) But this is a stronger argument for reforming all PACs than for cracking down on crypto PACs in particular.

SBF gave a lot of money directly to PACs, and those donations were made public. But via his trading firm, Alameda Research, he also donated millions to his brother’s nonprofit, Guarding Against Pandemics — but it isn’t required to disclose SBF or other donors. Certainly its 2021 tax record (pdf) makes no mention of them. If FTX hadn’t folded, these contributions may have never come to light.

The problem wasn’t just that the alleged source of the money was stolen funds. It was also the way the PAC system makes it easy to cloak where money comes from — and that’s a bigger problem than crypto.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Have a weekend as buoyant as bitcoin,

— Samanth Subramanian, Weekend Brief editor