A cocoa crisis

The world is disintegrating in front of our eyes — and we may not even have enough chocolate to tide us through.

Hi, Quartz members!

In the West Loop area of Chicago, the air smelled of chocolate; one reporter, in a segment of This American Life, said it was “the smell of magic.” The source was a long, biscuit-brown building, in which the Blommer Chocolate Company processed cocoa beans beginning in 1939. For a long time, Blommer was the largest independent cocoa processor in North America. But late in March, it announced the shuttering of its Chicago factory, laying off 226 workers. It had just become too expensive to run, Blommer said.

As a one-off, the closing of an old factory isn’t remarkable. But it comes as part of a wider pattern. Barry Callebaut, the world’s largest manufacturer of bulk chocolate, plans to shut down a plant near Hamburg, in Germany and another facility in Malaysia. It has cut roughly 18% of its staff. Hershey, the American chocolate giant, found itself downgraded from “outperform” to “neutral.” Across the industry, the volume of bean “grindings” — to be turned into chocolate — dropped by 2.5% in the first quarter of 2024, according to the European Cocoa Association (pdf).

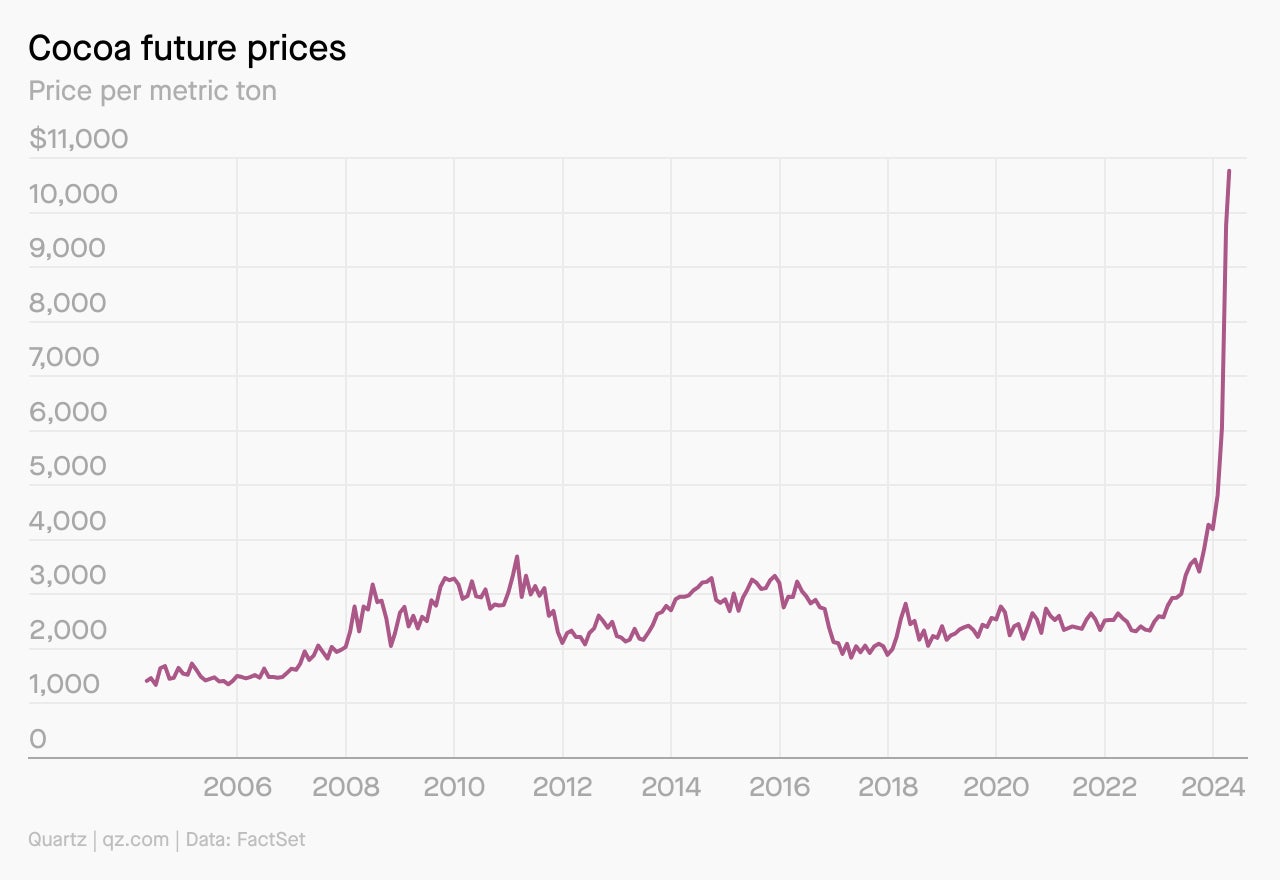

The crisis is being driven by the steepening price of cocoa, which has hit a record high and strained the margins of chocolate producers and cocoa processors everywhere. Futures prices for cocoa were up almost 6% in Thursday trading, to nearly $11,126 a metric ton, double the previous peak that was registered in the 1970s. Globally, cocoa prices have more than doubled already this year. This year, Barry Callebaut predicts a global shortfall of 500,000 tons of cocoa, roughly 10% of the worldwide market. Put simply, there are no beans out there to buy.

The world is disintegrating in front of our eyes — and we may not even have enough chocolate to tide us through.

CHARTED

QUOTED

There is literally a supply reason behind that. Initially we know that the weather obviously was impacting the crop volume in Côte D’İvoire as well as in Ghana significantly in the main crop last fall. That was probably the first element.

The second element that led to these price spikes were driven by large industrial players ordering very late, actually very, very late. And that whole situation then got amplified...by hedge fund activity that actually played on top. So the thing went vertical.

— Peter Feld, CEO of Barry Callebaut, on his company’s earnings call a week ago

THE QUOTA SYSTEM

Peter Feld was being somewhat facile when he attributed “a supply reason” and “the weather” to the cocoa crisis. He made these sound like passing phenomena. The truth is that they’re both systemic problems that corporations like Barry Callebaut — as well as those that have nothing to do with chocolate — have ignored for years.

Two-thirds of the world’s cocoa is produced in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. It’s certainly true that both countries have been hit by spells of prolonged drought and heavy rain. Flooding damaged the crops, but also left them prone to black pod disease, and in February, a west African heatwave sent temperatures above 40 deg. Celsius (104 Fahrenheit). Both of these are attributable directly to the results of climate change, according to a researcher with the Royal Netherlands Metrological Institute who spoke to Voice of America. For years, scientists have warned about the effects of climate change upon agriculture and food security, urging governments and companies to take drastic action against carbon emissions. Instead, progress has been incremental at best.

The other systemic problem has been the low prices that have traditionally been paid out to cocoa farmers in west Africa, which have left them unable to safeguard their plantations. Last year, an Oxfam report found that Ghanaian cocoa farmers have seen their incomes fall by 16% since the beginning of the pandemic — even as the confectionary profits of the world’s four biggest listed chocolate companies rose by that exact same figure. “Ghana produces around 15 percent of the world’s cocoa beans, but receives only about 1.5 percent ($2 billion) of the chocolate industry’s estimated annual worth of $130 billion,” Oxfam said in its statement. Multinational food giants have talked for years about paying fair incomes to cocoa farmers. But in practice, according to a 2023 report from Cocoa Barometer, “not a single large chocolate or cocoa company is paying higher prices at farm gate level.” Little surprise, then, that farmers are unable to protect their crops from floods, or irrigate them in spells of dry heat.

ONE 🍫 THING

Not much has changed over the past century. In 1938, the cocoa farmers of the Gold Coast (as Ghana was then called) staged an agrarian strike. “The farmers have agreed that unless the Europeans increase their price, they are not going to sell them any cocoa,” the journalist George Padmore, a committed pan-Africanist, wrote in The Crisis, the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Padmore identified a Unilever subsidiary as one of the most predatory companies buying African cocoa, pointing out that Unilever had made more than a million pounds in profit the previous year.

Today, too, the Ivorian cocoa producers’ union is threatening to go on strike, as they did in 2006, in a bid to earn better incomes for their harvests — and to impress upon the world a basic truth: If you want someone to farm the things you wish to eat, you must ensure they earn enough to want to keep doing it.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Have a sweet weekend!

— Samanth Subramanian, Weekend Brief editor; and Melvin Backman, staff writer