Hello, Mister Chips

Can the United States reasonably spend its way back to chip dominance?

Hi, Quartz members!

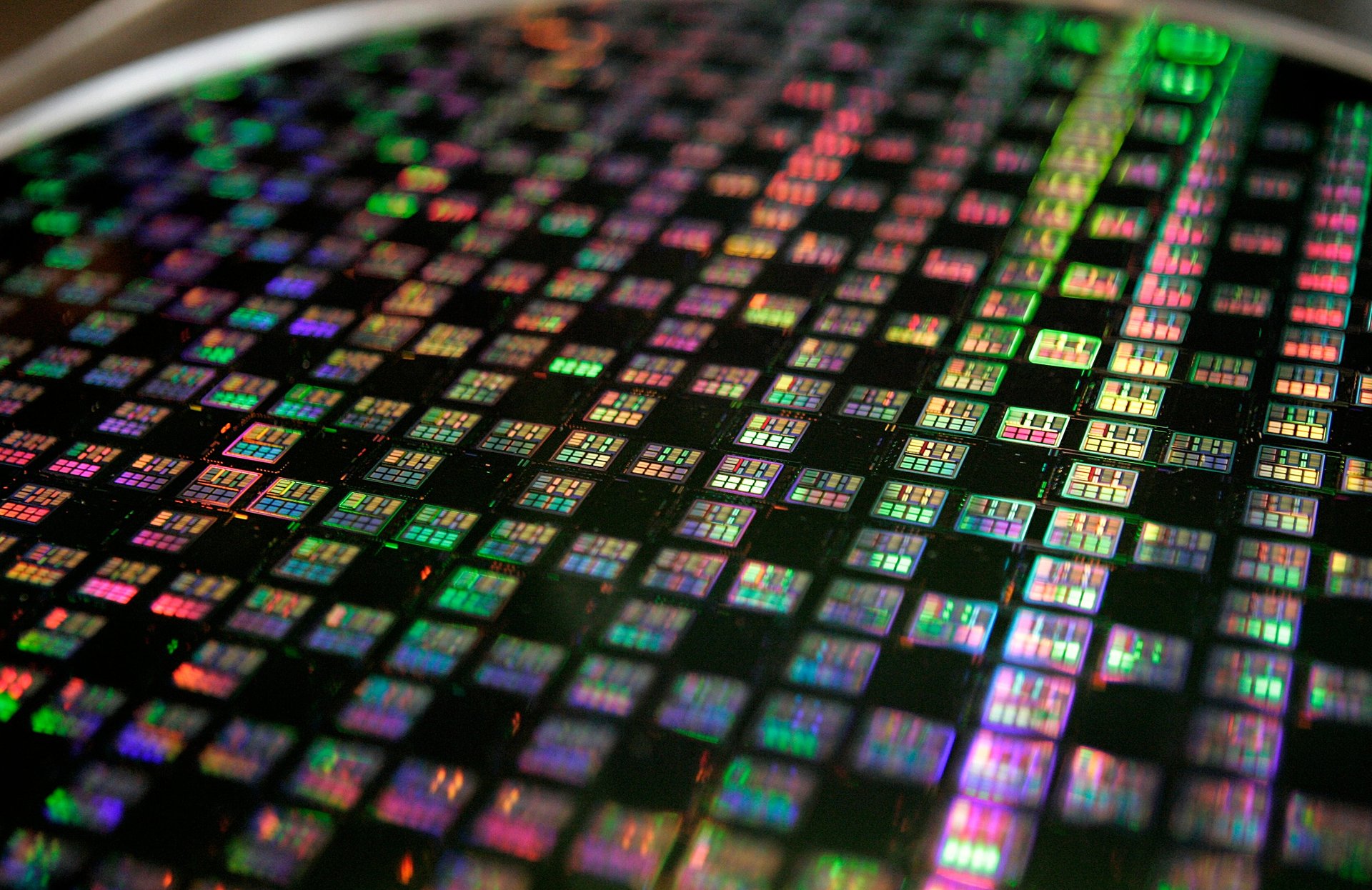

The silicon chip that powers the world’s electronic technology was invented in the United States back in 1959 by engineers Jack Kilby and Robert Noyce. Kilby won the 2000 Nobel Prize in Physics for his efforts, while Noyce died in 1990, but not before he’d founded Fairchild Semiconductor and effectively created Silicon Valley.

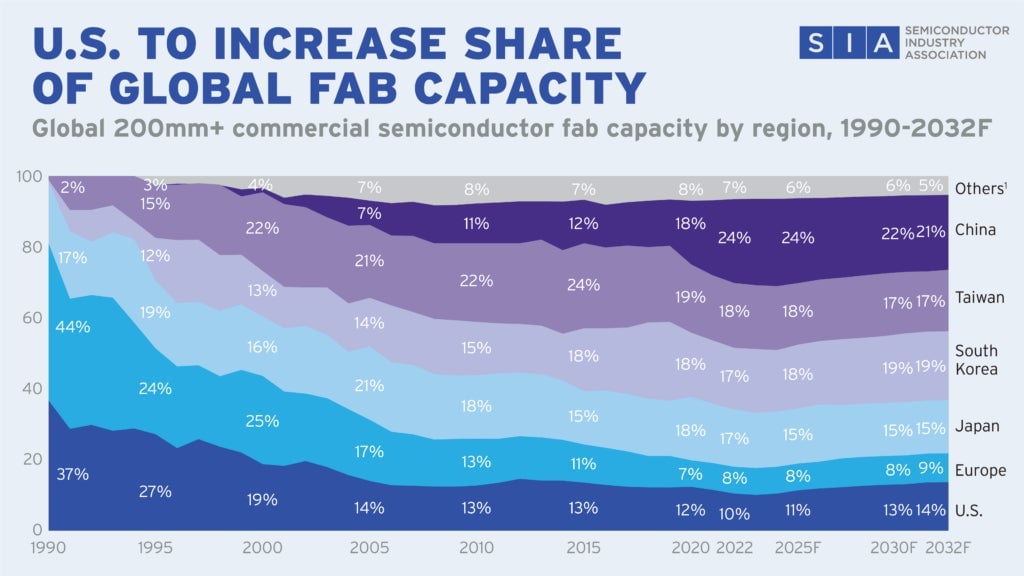

Chips made in the U.S. by Fairchild and by Kirby’s employer, Texas Instruments, powered the early IT revolution. As recently as 1990, the U.S. was still the world’s top chipmaker, comprising 37% of global output. But by 2020, that number had fallen to 12%, with three-fourths of global capacity in Asia. And the future promised to be even dimmer, with only 6% of new investment slated for the U.S., and China growing to hold 40% of new chipmaking capacity by 2030.

The pandemic showed how badly the chip industry and its customers could be hurt by supply chain disruptions. Automakers had lots full of unsold cars lacking the microchips that controlled everything from emissions to brakes. Chip-controlled respirators were in short supply. Smartphones and computers were chipless just as demand exploded. And the post-pandemic interest in artificial intelligence applications has increased demand for cutting edge chips.

Adding to the pressure to ensure a steady supply of chips to U.S. industry have been the increasingly loud threats by China to invade Taiwan, which produces about 60% of the world’s chips — and 90% of its most advanced ones. And while the U.S. leads in chip design not just for classic control purposes, but also for the exploding field of artificial intelligence, the country doesn’t manufacture or package any of the leading-edge chips.

“The brutal fact is the United States cannot lead the world as a technology and innovation leader on such a shaky foundation,” Commerce Secretary Gina Remundo said in February. Now the U.S. is taking a specific tack to firm up that foundation: spend big on rebuilding it.

The U.S. opens its wallet

Only now is the Biden administration doing what Taiwan, China and other Asian chip powerhouses have been doing for years: targeting subsidies and tax breaks for the construction of new chip plants from New York to Arizona, reshoring production and rebuilding a domestic supply chain. That’s due to the CHIPS and Science Act, and since it was passed two years ago, $53 billion in grants and $75 billion in loans have been earmarked for the effort to bring back American dominance across the field.

It’s in the last few months that the money has begun to flow. In March, the Biden administration gave Intel $8.5 billion in grants and $11 billion in loans to build a new chip plant near Phoenix, along with support for others in Ohio, New Mexico and Oregon. Intel is investing more than $100 billion in the projects, which it says will create 10,000 manufacturing jobs and 20,000 temporary construction jobs.

Just on the other side of Phoenix, the world’s largest chipmaker, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, or TSMC, is building a $40 billion plant. Outside Syracuse, New York, CHIPS funding will give Micron, a U.S. based chipmaker $6.14 billion to help build four massive clean room fabs, as chip factories are known, and a fifth in Idaho, as part of a two-decade, $125 billion investment by the company.

The prospects for reviving the American chip industry are good, says the Semiconductor Industry Association, which projects a tripling of domestic semiconductor manufacturing capacity by 2032. With the U.S. share of advanced logic chip manufacturing to hit 28% of global capacity by 2032, up from 0% in 2022, the United States could capture 28% of global capital spending on chipmaking over the next eight years. And without the CHIPS Act, the association calculated that the U.S. would have locked in only 9%.

Charted: The United States needs to pick up the pace

Taiwan, China, and the great chips of the East

Ever since the end of China’s civil war, when the remnants of the nationalist Kuomintang fled the mainland in defeat in 1949 and settled in Taiwan, the Communist government in Beijing has coveted the island, and threatened to take it back, by force if necessary. But China’s attachment to Taiwan has only grown as the island nation has become the world’s most important microchip maker.

Taiwan produces 68% of the world’s chips, mostly through one company: TSMC, which holds a market cap of $636 billion. And China needs those chips to power its own industry.

Despite spending tens of billions of dollars to be 70% self-sufficient by 2025, China only produces about 16% of the chips it needs, and imports over $400 billion of semiconductors a year. Taiwan’s increasing talk of independence — the separatist Democratic Progressive party won a third term in January — was fueled in part by the Chinese Communist government’s heavy hand in Hong Kong, and has infuriated Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

Xi has threatened to impose sanctions or a blockade on Taiwan and even to invade the island, attaching it to China by force and possibly seizing its chip factories. Some analysts say China would be unable to run the factories by itself, and their supply chain is so dependent on global sourcing, that an invasion would be an own goal, undermining China’s own industrial base. Others say an increasingly unpopular Xi could decide politics outweighs economics. And that may be part of why TSMC is building a $40 billion plant in Arizona.

One ⚖️ thing: Whatever happened to Moore’s law?

Back in 1965, Gordon Moore, a computer engineer who later became CEO of chipmaker Intel, predicted the number of transistors on a chip — and therefore the chip’s computing power — would double every year. (In 1975, he revised that to every two years, after a decade of being proven right).

But nearly 60 years later, after increasing the computing power of ordinary machines by about 100,000 fold, Moore’s law may be on the verge of being overturned. The culprit? The basic laws of physics.

”It’s over,” Charles Leiserson, a pioneer of parallel computing, told the MIT Technology Review in 2020. As chips and their transistors get smaller, quantum mechanics takes over, and atoms start wandering where they shouldn’t.

Still, there’s a big divide in the industry. While Intel says Moore’s law still works, as the company makes costly improvements in chip manufacturing, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang has said that it’s no longer possible to keep cramming more transistors onto a silicon chip, but that artificial intelligence will continue to keep computer performance advancing, calling generative AI “genuinely a new computing platform.”

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Have a chipper weekend!

— Peter Green, Weekend Brief writer