Hi, Quartz members!

When word leaked last week that Red Lobster, the restaurant chain known as the Olive Garden of the sea, was filing for bankruptcy protection, credulous media — including Quartz — swallowed a tale that in a down economy for fast-service restaurants, the company’s $20, all-you-can-eat shrimp specials were what dragged the chain’s 687 restaurants beneath the waves.

But once the actual bankruptcy documents were filed with a federal court in Orlando, some new truths emerged: Red Lobster had been bleeding rent for a decade.

In a nutshell, private equity firm Golden Gate Capital bought Red Lobster and sold off all the buildings housing the restaurants to a real estate investment trust, which leased the buildings back to Red Lobster at premium rents, locked in for an average 25 years. That deprived the chain of needed flexibility. If traffic fell at a restaurant, they couldn’t negotiate the rent. Across 687 locations, in 2023 Red Lobster paid $190.5 million in rent, of which $64 million was from stores that should probably have been closed.

Compare that with the company’s $76 million net loss for the year, and some dumb financial decisions — among them handing inventory management over to its vendors, including Thai United, who happened to be not just the supplier of the Ultimate Endless Shrimp (more on that later), but also Red Lobster’s largest shareholder.

That left Red Lobster saddled with $1 billion in debt, and in six months last year its cash position collapsed from $100 million in the bank to $30 million.

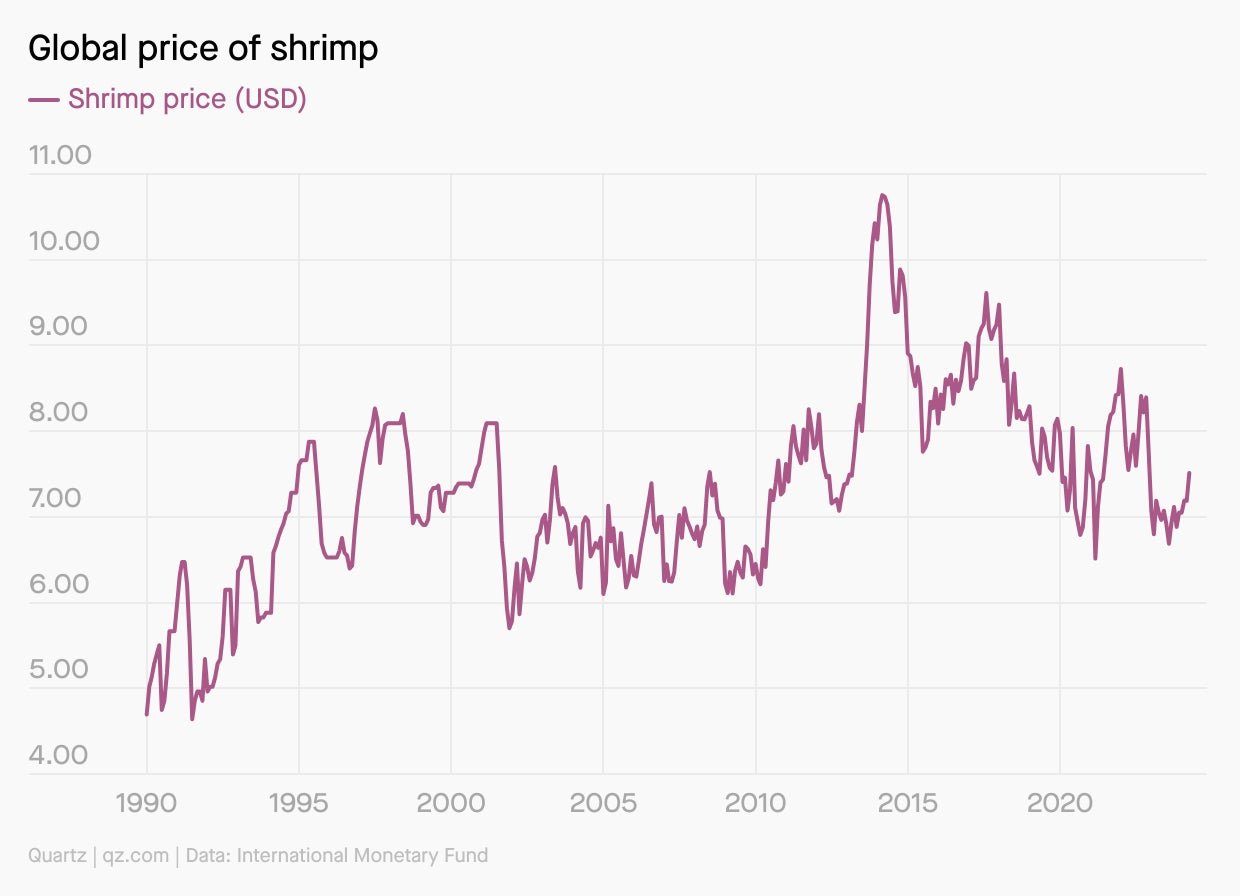

Charted: Shrimp in the tides

Stormy seas

But wait, there’s more. Red Lobster ran through five CEOs in five years, and its business model needed refreshing. Foot traffic hadn’t recovered from pre-pandemic levels — but more importantly, as R.J. Hottovy, an analyst with Placer AI, told Quartz, labor’s getting more expensive, food costs are going up, people dine out less now that they work from home, and the brand was getting stale.

“Overall, people are preparing more food at home,” said Hottovy. And when they go out, they don’t want the same old-same old. “People are gravitating to newer concepts, they want variety and change in dining out. They want more experiential dining — revolving sushi bars, play-oriented restaurants like Dave & Busters,” and not just seafood on the menu.

Red Lobster’s brand is strong enough to survive the reorganization, said Hottovy, and the bankruptcy proceedings will let them shed many of the expensive leases. Already, some 50 locations are being shuttered. But we’ve probably seen the end of endless shrimp.

Fishy business

About that ultimate endless shrimp. The promotion actually cost Red Lobster about $11 million, and did not seem to bring in the extra foot traffic it promised. So how did that happen?

Well, Thai United, which paid over $500 million for its stake in Red Lobster, had a clear view of how to use that investment profitably: turn Red Lobster into a major customer. According to Tibur’s court filing last May, it was Paul Kenny — Red Lobster’s then-CEO and a Thai Union appointee — who decided to add the bottomless shrimp bowl as a permanent menu item, over objections from other top managers. Tibur now says he’s “investigating the circumstances around these decisions,” and noted that Thai Union was granted exclusive rights to sell shrimp to Red Lobster.

“Thai Union exercised an outsized influence on the Company’s shrimp purchasing,” Red Lobster’s latest CEO, a restructuring specialist named Jonathan Tibus, wrote in the bankruptcy filing. And by law, related entities have to keep their transactions at so-called arm’s length.

One 🏠 thing

So how did this sale-leaseback thing work, anyway? To be honest, it’s not that much different from some forms of deed theft — you know, the mortgage scam where someone sees the bank is about to foreclose on a home, swoops in to make the deed-holder an offer, and effectively becomes their landlord.

That can be illegal when it comes to personal residences, but not with commercial real estate. In this case, when Golden Gate Capital bought Red Lobster from Darden Restaurants for $2.1 billion back in 2014, it immediately flipped the real estate to a real estate investment trust called American Realty Capital Properties for $1.5 billion. That meant Red Lobster had to pay rent on every location at a price that rose 2 percent a year for the next 25 years, giving ARCP a steady income of 9.9%, a year on the $1.5 billion it paid for the restaurant buildings.

In a normal sale-leaseback, Red Lobster would have put that $1.5 billion to work — paying down its debt, or investing in new locations, say. But in the world of private equity, Golden Gate just pocketed the money, and continued to take home a share of Red Lobster’s profits, until it sold its stake to Thai United in 2016 for $575 million. ARCP’s chief operating officer at the time, Lisa Beeson, noted her firm bought the locations at “below replacement cost.” As Tibus wrote, “a material portion of the Company’s leases are priced above market rates.”

But bankruptcy will let Red Lobster shed many of those leases like a molting lobster.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Have a wavey weekend!

— Peter Green, Weekend Brief writer