It's too damn hot!

Another record-breaking hot summer will hurt the economy

Good morning, Quartz members!

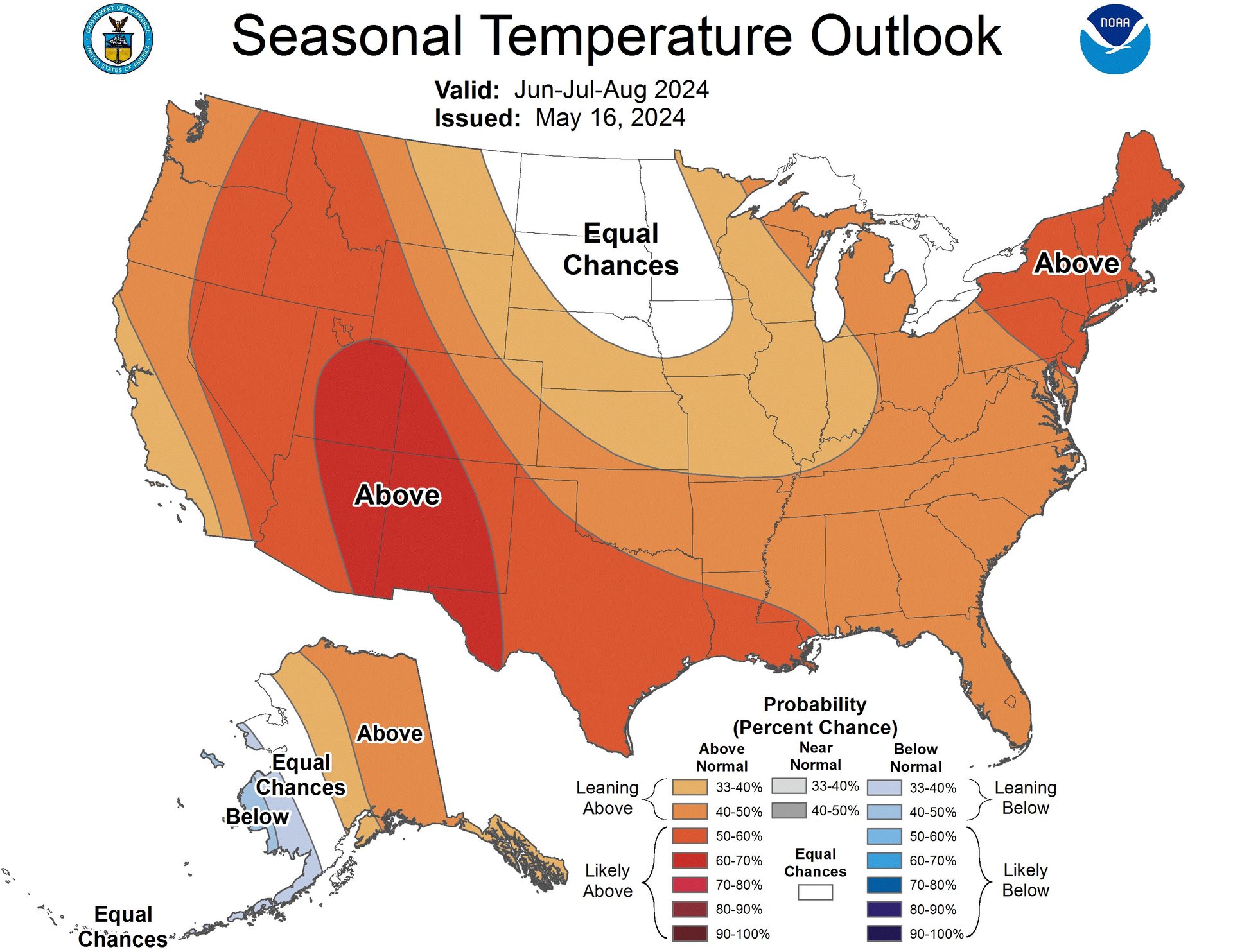

It’s gonna be another scorcher. The mercury will soar again this summer, with AccuWeather predicting temperatures at least two degrees above average across the country for the next three months. New York City can expect two dozen 90-degree days, twice last year’s total. In Boston, that may be quadruple. In Brownsville, Texas, temperatures are expected to break 100 degrees again next week. That’s uncomfortable for many people — and for outdoor workers, it can be deadly (more on that later). But high temperatures also affect the economy, shaving whole percentage points off of GDP.

Farmers may have to plant earlier, crops may rot or wither before they ripen, or it may just be too damn hot out to harvest. Besides the obvious sectors — farming, construction and other outdoor businesses — high heat can affect real estate (who wants to live in a desert?), manufacturing, insurance, retail, travel, and of course, logistics.

Sure, you can turn on the A/C, and that can increase revenue for power producers and utilities. But that only goes so far. And extreme heat can strain many cooling systems to the breaking point. Take the Arizona Wilderness Brewing Co., a Phoenix-area craft beer producer. About 60% of its revenue comes from its outdoor beer garden, brewery exec Zach Fowle told CNN. But in the midst of a three-week streak of 110-degree heat in the desert city last summer, the outdoor patios were empty, and A/C units were breaking down as they struggled to keep the beer — and indoor patrons and worker s— cool in the heat.

Trucks overheat, warehouses get too hot for workers (un-air conditioned Amazon warehouses made the news a few years ago after a series of employee deaths from heat stroke), rail lines, bridges, and traffic lights malfunction in the heat, and many manufacturing lines have to shut down when temperatures rise. Overheated electric transmission lines and drought-fueled high temperatures led to California’s massive wildfires in 2018, killing 85 people and costing the U.S. economy $148.5 billion, or 0.7% of the country’s GDP. A third of that was lost outside California.

In excessively high heat, consumers stay home, tourists abandon overheated destinations, food spoils in supermarkets and warehouses, and extreme weather-related disruptions alternate high heat with devastating rainfalls. The effect may not be noticeable at first, but it snowballs, to pick a wishful metaphor — and can significantly slow the economy.

Each one-degree Fahrenheit rise in average summer temperatures cuts economic output by 0.15 to 0.25 percentage points, said Ric Colacito, a professor and macroeconomist at the University of North Carolina’s Kenan-Flagler Business School who mapped state-level economic activity to excess temperatures. Just two degrees — this summer’s forecast — could cut about $150 billion from the country’s economic activity.

“It’s a little like saving a small amount of money every month,” he told a campus magazine. “On a month-by-month basis it doesn’t change your savings account by a whole lot, but once you compound that small amount over 20, 30, 40, 100 years, it becomes a big number.”

Climate change has the potential to “significantly alter the economic playing field,” by creating winners (those who can adapt) and losers (those who can’t), the economist R. Jisung Park writes in a new book called “Slow Burn: The Hidden Costs of a Warming World.”

In a recent study by the Atlantic Council, heat-related productivity losses totaled $100 billion in 2020, and were expected to reach $500 billion by 2050.

That makes man-made climate change, the chief cause of the rising heat, a key matter for the economy. “We need to trust the science that temperatures are bound to increase. If we keep neglecting it, then our research suggests that the economy is going to grow at a slower pace,” Colacito says. “And a slow economy is something we should care about. It may mean less jobs. It may mean less opportunities. It may mean that our children and grandchildren are going to have less resources going forward.”

Charted: It’s getting hot out there

Working in the heat

Two of the worst places to work in high heat are on a farm and in an Amazon warehouse. Over the past decade or so, a number of workers have died of what were likely heat-related illness in Amazon warehouses across the U.S. In 2022, three Amazon workers died in New Jersey warehouses, and the Bergen Record newspaper said all of the deaths were initially reported as heat-related. Amazon disputes the accounts, but NBC News reported that within weeks of the July death of worker Reynaldo Mota Frias, air conditioning had been installed at the Carteret warehouse where he died.

The U.S. government’s main worker safety agency, the Occupational Health and Safety Administration, calls heat illness “a growing workplace safety and health concern.” And according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, an average of 43 workers died due to environmental heat from 2011 to 2021. In 2022, OSHA began inspecting job sites during heat waves, with a focus on industries most at risk of heat illness, such as bakeries, farming, warehousing and mail delivery. OSHA has stepped up education and enforcement. And in one notable case it slapped a farm labor contractor in Florida with a violation for not supplying water, shade, and rest to a 28-year old farmworker who died of heat stroke in 2023. The National Weather Service has even devised an interactive heat danger map for outdoor workers.

But efforts to protect workers from excessive heat are facing opposition from some states where the heat is worst. In April, Florida’s Republican governor, Ron DeSantis, signed a bill blocking local governments from requiring heat protections for outdoor workers, after Miami-Dade County passed its own rule to keep farmworkers and construction workers safe from extreme heat.

Travel troubles

Higher temperatures are the bane of vacation travel: Cars overheat, air conditioning conks out, nighttime can offer little relief, and air and rail travel get delayed. With trains, the problems are obvious — heat causes rails to expand and misalign, and electric power lines to droop, meaning trains have to slow, or sometimes stop altogether. With cars, heat can over-inflate tires, make asphalt roads sticky — especially for those large trucks in front of you on the highway — and running the A/C in a traffic jam will overheat your engine. High heat is particularly bad for airplanes, and that’s mostly down to physics.

As air heats up it expands — that means it’s less dense, and the less dense air is, the more a plane’s engines struggle to keep it aloft. “Hot air is thin air,” says Dr. Bob Thomas, an assistant professor of Aeronautical Science at Embry‑Riddle Aeronautical University. The thin air reduces the lift planes rely on to take off, and the thinner air also produces less thrust from an airplane engine, giving it less power.”

To get a plane off the ground in summer, airlines may lighten a plane’s load by removing passengers and bags. At peak season, when there’s little excess capacity, passengers and their bags are delayed sometimes by days.

Airlines and pilots may also delay flights until cooler evening or early morning hours, leading to cascading disruptions across an entire airline system, and leaving passengers roasting on runways as they wait for a takeoff slot. A 2017 study by Columbia University said up to 30% of all U.S. flights might be subject to weight limits in hot weather. And there’s not much to be done about it unless either the planet cools — or the laws of physics get amended.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Have a cold drink and wear a sunhat!

— Peter Green, Weekend Brief writer