The great American office space slump

Work from home is killing the commercial real estate market.

Hi, Quartz members! There’s a good chance that if you are reading this over the weekend, you won’t be going into an office on Monday. In fact, so many people are working from home for part of the week that the U.S. office industry is in deep financial trouble.

Suggested Reading

Let’s take a look at the problem.

Related Content

The office space slump

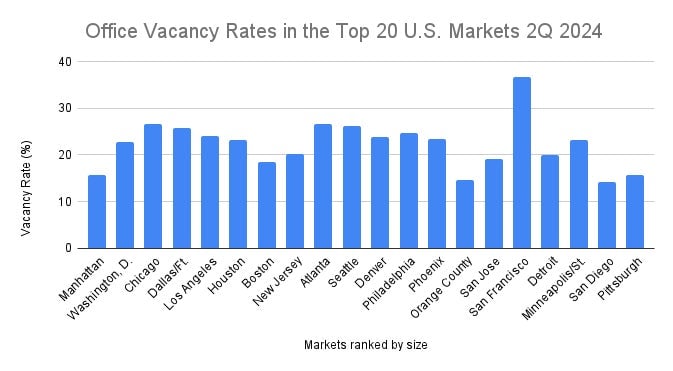

The numbers are horrifying and so are the anecdotes. Two years after the COVID-19 pandemic eased, urban downtowns are still empty across the country. Office vacancy rates are above 20% nationwide, building owners are handing over their keys to banks, and once valuable properties sell for a small fraction of their last purchase price at firesale auctions. In some city centers, there’s talk of the Urban Doom Loop — a phrase coined by Columbia Business School Professor Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh that refers to the empty offices created by employees working from home, which leads to shuttered businesses in downtown areas and the evaporation of a city’s tax base.

We’ve all seen the pictures of San Francisco, New York and Washington: empty offices, closed shops, and homeless people sleep on sidewalks.

But how bad is it really? Weekend Brief spoke with leading experts, landlords, investors, analysts and others to find out. The answer: Pretty grim, but it might get better.

The occupancy shock

In the second quarter, the national office vacancy rate hit 20.1%, rising for the third quarter in a row and marking the first time office vacancies were recorded at over 20%. The reason: Work from home isn’t a temporary thing anymore, it’s the new normal. Moody’s economists call the change “a lasting shift” in workplace usage, and a recent Federal Reserve study showed 28% of respondents said they’d look for a new job if they couldn’t work from home for at least part of the week.

The Moody’s economists say they see office vacancies peaking at about 24% in early 2026, before eventually dropping to 14% over the next five years. That’s partly because people have changed the way they work. New leases signed this year are for spaces about 25% smaller than those signed for the same number of employees before the pandemic, said Jessica Morin, who leads office research at the real estate firm CBRE.

Morin sees the situation easing, slightly, pointing to CBRE research that shows a rise in so-called net absorption, the difference between the amount of space leased and the amount of office space vacated. It rose by 2.4 million square feet in the second quarter of this year, the first increase in six months.

Still, on the peak in-office days of Tuesdays and Wednesdays, Morin said, only about 60% of office space is used. “We’ll have a lot more desk sharing than we had pre-pandemic,” she said. A bright spot is that office layouts are changing. “We need collaboration spaces because the hybrid [plan] brings you into the office to work with a team, and that’s offset some of the reductions in desks,” she added.

Morin is an office optimist. She noted that the hardest hit are the 10% of office buildings that are the least desirable: older, rundown and in less attractive areas. The top 8% of office space is doing just fine, and new towers are still going up, though far fewer than before the pandemic. But she said a growing economy will bring in more workers, and even with WFH, they’ll be refilling most of the decent office space. As for the rest: It’ll be torn down or converted to hotels and apartments.

Where’s the action?

Atlanta, Chicago, Dallas, Seattle, and of course San Francisco, are among the worst hit office markets, with vacancy rates above 25%, according to CBRE.

One market that has not suffered as big a hit is Miami, where the vacancy rate was 14.8% in the second quarter. “The growth from companies that have migrated to Miami during the past four years has offset the hybrid-work downsizing,” said Tere Blanca, a commercial broker and adviser in Miami. For Miami developers, it’s interest rates, not occupancy that have been the problem, especially for investors with floating rate debt or loans coming due. And with demand for new housing still strong in Miami, Blanca says many aging and unwanted Class B office buildings are likely to be torn down and replaced with shiny new condos.

The debt problem

It’s not just the empty space that’s a problem: Many landlords borrowed heavily to buy their buildings when interest rates were near zero, and their thin margins were based on high rents, high occupancy rates, and low interest rates. All that’s gone now, and with commercial mortgages renewing every seven to 10 years — not every 30 years as with home mortgages — a massive crunch is coming.

Are U.S. banks prepared? Many have yet to mark their loans to market, a finance phrase for using the actual market value of a property (or a financial instrument) when calculating the value of a bank’s assets.

Over the next two years, more than $1 trillion in commercial real estate loans will come due, according to a recent study by The Conference Board, a corporate-funded business research group based in New York, and many landlords won’t be able to afford to refinance — leaving banks holding the bag. Much of that is due to the Fed hiking interest rates by 5 percentage points since March 2022, from 0.25 percent to 5.25-5.5% in July 2023, where it has stayed ever since. We’ve already seen what happens when real estate values sink and loans can’t be paid or refinanced. That’s what gave us the Great Recession of 2008, although that was largely fueled by home mortgage lending.

So far, banks including First Republic, Signature, and New York Community Bank have all folded after loans on real estate, especially commercial real estate, couldn’t be paid off.

Extend and pretend

So why aren’t real estate investors hurling themselves — or their bankers — through the sealed windows of their two-million square-foot, 30%-leased, Zaha Hadid-inspired LEED Platinum office towers?

To avoid problems, many banks are crossing their fingers and hoping the market will recover before the debt comes due. “A lot of banks are willing to extend the existing loans,” said Rob Gilman, who leads the real estate practice at Anchin, a New York-based accounting firm.

It’s called “extend and pretend,” Gilman noted. But why would banks pretend? “Part of the reason,” he said, “is they haven’t marked their losses down to what I believe is the right level.”

Debt danger

The danger is biggest to smaller and mid-sized banks that make many of the loans to mid-level office building owners, and which haven’t got the deep pockets of a Chase or Citibank to withstand the cash crunch that would come with a large number of defaults and fire sales.

“Many properties that were acquired prior to the pandemic, in the 10 years leading up to 2019, were acquired on the basis that interest rates were going to remain near zero and could be sold or refinanced at capitalization rates reflecting the then-norm, which today are inapplicable,” said Michael Cohen, a president at Colliers, a commercial real estate brokerage and advisory firm in New York.

A landlord or investor who bought a building on margin and could afford interest payments of less than 1% three years ago is now paying up to five times that in interest. And many of those loans are now coming due.

“This realization of value loss will be a slow burn because most office buildings have long-term leases which allows the owners to ‘ignore’ losses until they are absolutely forced to,” said Tyler Wiggers ,of the Center for Real Estate Finance and Investments at Miami University’s Farmer School of Business. The squeeze will come, he said, when enough tenants don’t renew or significantly cut the amount of space they need — and the property stops producing enough rent to cover costs, or even worse, it needs a new air conditioning system a lobby refurbishment and tenants simply leave.

Taxes and interest rates

Taxes are another issue for landlords whose properties are falling in value, said Anchin’s Gilman. “You can’t just give back a key these days and like, ‘OK, you know, I lost my property. I must have a tax write off,’” Gilman said. U.S. tax laws are very favorable to real estate, and many landlords can accumulate legally deferred tax bills that they pay off once they sell their property. But if the building’s value has declined, they may be on the hook to the IRS. That makes them even less able to pay off their loans.

“Prices need to drop much lower in order for the markets to reach a supply-demand equilibrium,” Wiggers added. And even then, a lot of what’s currently used as office space will have to be converted — affordably, for developers — into apartments, storage space, or other uses. “But someone, or some parties, like the current owner and probably the debt provider, will have to suffer material losses to get us there,” Wiggers said.

And that could be a problem for the financial system, not unlike the 2008 crash.

“The damage could metastasize into a full-blown financial crisis if scores or even hundreds of small- and midsize commercial banks fail simultaneously,” Conference Board chief economist Dana M. Peterson wrote in the July issue of the Harvard Business Review. “A worst-case scenario might include contagion to other economies and banking deserts across the U.S.”

Not everyone agrees. Up at Harvard itself, economics professor Kenneth Rogoff, an expert on financial crises, concedes there will be casualties. “There are definitely going to be a lot of firms that invest in commercial real estate who are going to see their equity wiped out, and the losses will be so big — with many buildings selling for half of what investors paid for them — that debt will get hit hard also,” Rogoff told a university publication in June. “On its own, though, this will not cause a full-blown financial crisis, especially in the context of a still-solid global economic outlook.”

A buying opportunity

Cohen, who manages his family’s extensive New York City real estate holdings alongside his work at Colliers, said well-managed real estate firms have been setting money aside and will weather the downturn — even if they have to sell some lower-quality properties at a massive discount.

Long-term real estate players will return to the days of buy and hold, when they would purchase buildings or lots and wait years until they had a lot large enough to build on — or a client big enough to take a building, he added.

Private funds, called secondary funds, have also popped up, ready to buy offices at a significant discount. These funds tend to buy properties that are fairly stable, but are underperforming for their current owner, who would prefer to take a hit now. That offers discounts of more than 25% to investors who can wait for their returns.

“It’s a buying opportunity,” said Cohen.

Thanks for reading, and don’t forget to go into the office this week.

— Peter Green, Weekend Brief writer