Quartzy: the good influence edition

Happy Friday!

Happy Friday!

I’m writing you today from the south of France, where I’ve been covering Cannes Lions—a weeklong festival that attracts thousands of high-powered media and marketing executives, creative directors, advertising salespeople, and show-business types for panels and parties, addressing topics ranging from leadership and creativity to AI and blockchain.

The event attracts people at the very tops of their games who work for (or founded) the world’s biggest brands, discussing how they’ve gotten there, what they’re doing right, and how other alpha types might accomplish similar feats. Among the buzzwords bandied about are “authenticity” and “vulnerability,” but on a stage a stone’s throw from a helicopter pad at the end of a pier packed with yachts, these qualities can feel hard to come by.

So it was striking when Whitney Wolfe Herd—the 28-year old founder of the dating app Bumble, which was recently valued at more than $1 billion—took a long pause during an onstage interview with Hearst’s Joanna Coles, and said: “I have insane anxiety and I am very nervous up here, so thanks for bearing with me.” Coles told her she had no reason to be nervous, considering her great story, but Herd took the moment:

“I think it’s important to be candid about that too. People think you get 30 million downloads on an app, all of a sudden, everything is just hunky-dory perfect all the time, but that’s not life. I think it’s natural to have low moments, even when things go really well.”

It was a rare and refreshing admission from someone who exemplifies the millennial entrepreneur (she recently appeared on the cover of Forbes’ “30 under 30” issue) and it exposed a disconnect between the two-dimensional way we often perceive people in the Instagram age—glamorous, happy, successful—and their complex human realities.

Which brings us to “influencers.” By now, we’re mostly accustomed to the idea that some people on Instagram are paid by brands to promote their products. This multibillion-dollar marketing channel was originally lauded for its personal and unpolished “authenticity,” an appeal that has diminished greatly as influencers have become more savvy at, well, influencing.

Here this week, Unilever—the parent company of brands including Dove, Ben & Jerry’s, and Hellmann’s, and one of the world’s biggest ad spenders—announced it would no longer work with influencers who buy followers, a shady but common practice in the industry. It seems like an obvious step, but it’s an important sign that companies build trust by taking responsibility for their chains of “influence,” like they do for their physical supply chains.

A good influence. Olympic fencer Ibtihaj Muhammad, the first Muslim woman to represent the US in the games (and the first hijab-wearing Barbie doll), said she made an important decision early in her athletic career, which she described as one “built on happiness.”

“I chose to be happy whether I won or I lost,” she said, adding that there were a great many losses along the way. “And when we do that we can perform at our best.”

Actor Kevin Costner, in Cannes to promote his new TV show—”it’s me on a horse,” he said—echoed that sentiment. “You work just as hard on a bad movie on a good movie, if you’re trying,” he noted.

A reader question from Rachel: How do advertisers balance the ethics of their work with their own moral compasses? Great one! Gloria Steinem talked with #MeToo founder Tarana Burke this week about why ads matter: “More than government, more than religion, more than any force in the world, advertising shapes our idea of what is possible,” said Steinem, arguing that ads can foster a “collective unlearning” of harmful biases and stereotypes.

Rik Strubel, a VP at the men’s hygiene brand Axe (AKA Lynx outside the US), talked on a panel with Quartz’s Jason Karaian about the dangers of toxic masculinity. The brand is trying to move away from laddish tropes about “real men” and sexual conquests, instead attempting to redefine itself with campaigns like “Is it OK for Guys…,” which explores the many things guys ask Google whether it’s okay to do (ie, wear pink, be the little spoon, cry).

On the ad agency side, Wieden + Kennedy chief creative officer Colleen DeCourcy, a founding member of a Time’s Up group for advertising, talked with Quartz’s Lauren Brown about the real costs and challenges of walking away from business that doesn’t align with hers ethically: “We get stuck trying to lead the right things, but not saying ‘I’ll give up that X-million dollars to feel right about my business. I know that it’s on no one but me to do that, and on no one but me to go out and find that new business to replace that revenue.”

No one said this would be easy.

It’s unlikely that the veteran ad man Sir John Hegarty would call himself a “creative,” but the man clearly knows a thing or two about making it happen. Here’s what he said when we asked him how he gets through creative blocks:

Go for a walk.

I do my best thinking when I’m not thinking. That’s why, just talking to somebody—having a conversation—it unblocks things.

Looking at a screen will never unblock your creativity. What I always say to creative people is, “unplug the computer and have a conversation with somebody.” Talk to them. You may find that they did something last night that’s really interesting—you might be able to use that.

Get out there. Just walk it off.

When you see somebody with their feet up on a desk looking out of the window, people think, “What are they doing? Why aren’t they working?” They are working.

Have a great weekend!

[quartzy-signature]

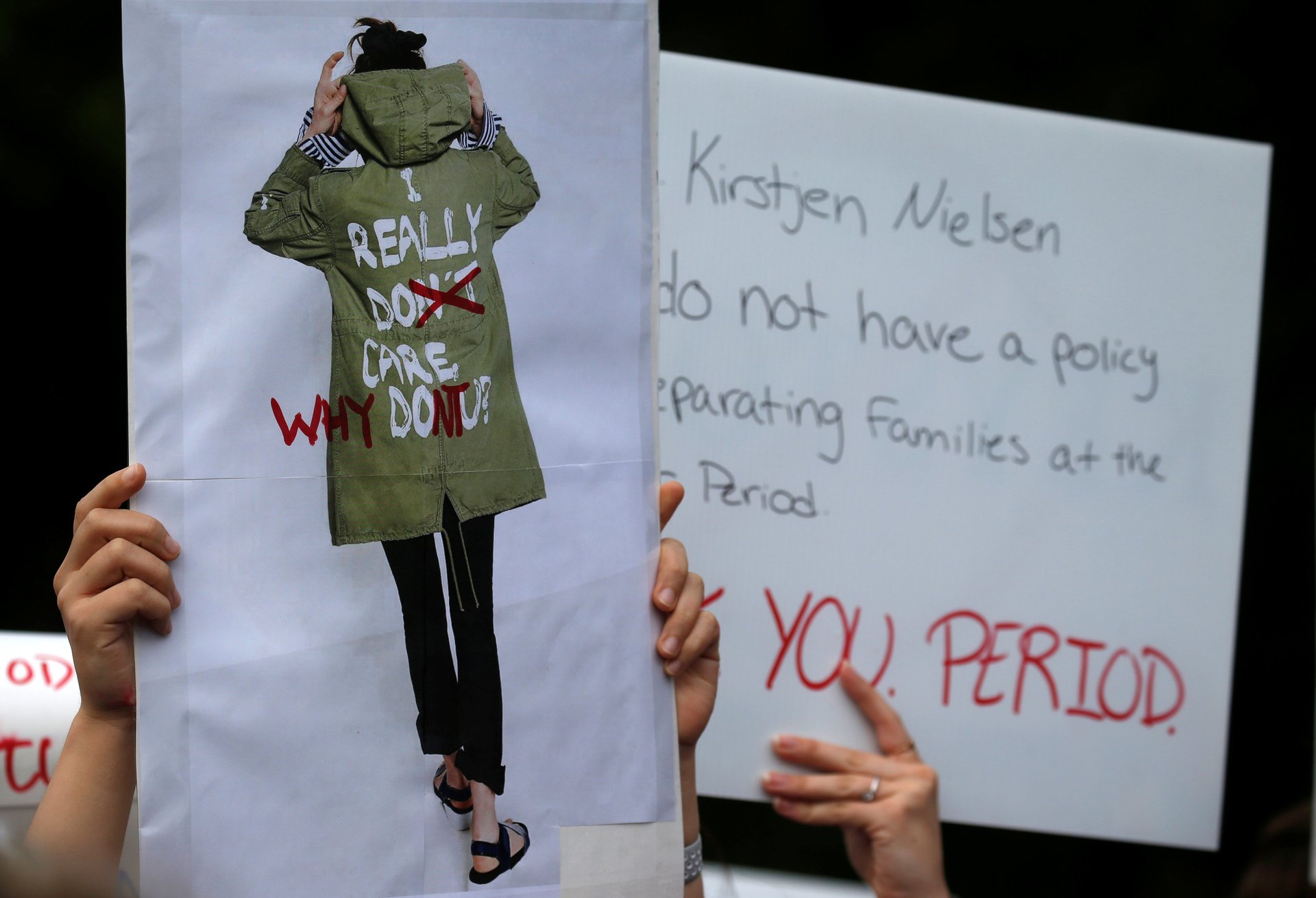

I’ve spent the last week in something of an alternate universe, surrounded by privileged and powerful people. This has made it all the more jarring to see alerts on my phone about the horror and confusion unfolding back in the US, where children have been separated from their families as a result of Donald Trump’s “zero-tolerance” immigration policy. This space is usually reserved for something fun you can do this weekend—make a drink, listen to Bey and Jay’s new album—and you should still do those things. But if you’re reeling from the news and want your voice to be heard, you could also attend one of the rallies planned across the US. Here’s a guide to how you can also donate, volunteer, and contact your representatives.