Is Virgin Galactic the next Tesla?

Dear readers,

Dear readers,

It’s the sixth edition of Space Business, Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extra-terrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: A Virgin goes public, business as usual at NASA, and the hunt for deadly asteroids.

🌘 🌘 🌘

At Quartz, we keep a secret list of private companies we suspect are plotting to go public. Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic was not on that list, but following a merger announced July 9, it will be the first “New Space” company—and the first human spaceflight company—to test public investors’ appetite for space business.

The omission is just one reason I’m not a venture capitalist (or an M&A reporter, for that matter.) Virgin Galactic represents one of the most ambitious companies in the sector, literally trying to create a consumer market that doesn’t exist (space tourism) after 15 years of hard work. My bet for the first space IPO was on one of the satellite data companies disrupting and expanding the existing market for remote-sensing; they’ve at least generated some revenue.

Adding to the fun is the way VG will hit the markets: It was purchased by a publicly-traded shell company operated by venture capitalist Chamath Palihapitiya, who raised money in 2017 to buy a private firm worth more than $1 billion. This approach to going public will allow VG to hide its past financial performance, and instead focus on the future.

The company’s valuation ($1.5 billion) is based on a set of assumptions through 2023 that will require big performance, including building a new rocket plane every year and finding more than 2,600 new customers to pay $250,000 each for a 20-minute trip to space—not to mention taking a vehicle design that has gone to space twice, and flying it 16 times in 2019 and 115 times in 2020.

Are the investors that Palihapitiya recruited happy with his purchase? Stock in the shell company, trading as IPOA, gained after the news. But anyone buying the stock now can redeem it for just over $10 once the deal closes, meaning that right now it’s a fairly low-risk bet to take on excitement around these shares.

At a lunch with investors in New York City, I’m told Branson and Palihapitiya made an analogy not to SpaceX, but to Tesla, Elon Musk’s electric car company. Tesla stock has been a darling of tech-obsessives and bête noir of the short-selling community. As even Musk himself has noted, Tesla does not typically trade on the fundamentals. Neither will Virgin Galactic, at least in the short term. It’s a sentiment play for investors excited about the future of space.

But any comparison with Tesla should reckon with what happens when the hype runs out. Tesla changed the way society thinks about electric vehicles, and now major auto companies are queuing up to run it out of business. Virgin Galactic may change the way we think about space tourism, but Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk are preparing their own offerings with far more capital behind them.

It’s downright impressive that Branson has financed Virgin Galactic for 15 years, and that its technologists and test pilots have actually built a reusable space tourism vehicle. With private funds running out, this new financing presents a big opportunity to fish or cut bait: This is either a sustainable business or not. But investors in other space ventures will be watching closely to see what the market reaction augurs for their own aspirations.

🌘 🌘 🌘

NASA would like to shift more of what it now does in low-Earth orbit to private companies, so the government can do more in deep space. Lawmakers weren’t very enthusiastic at a hearing yesterday on the future of the International Space Station. Here’s maybe the perfect quote for understanding the US space program, from Rep. Randy Weber, whose district is adjacent to NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC).

“When we partner with industry, how do we ensure that we don’t take jobs away from our NASA facilities?” Weber asked. “It’s critical that we ensure the commercialization of ISS will still model that of the space shuttle and ISS programs where integration, operations and other activities are still done [by NASA]—did I mention Johnson Space Center’s close to me? How do we ensure that that happens? We don’t want those jobs to go away.”

Simply put, this is why we don’t have nice things. NASA is not going to save money by maintaining all existing government jobs and adding private companies to the mix. Those following along at home know that the “commercialization” of the space shuttle and ISS were mainly delivered via uncompetitive contracts with guaranteed profits that didn’t save the government much money. Weber cited a more recent example: Boeing’s effort to build a new space vehicle for NASA, which subcontracted its flight control operations back to JSC. Boeing’s bid for the job was $1.6 billion higher than their rival SpaceX, which does its flight control in-house.

In Florida, the community around Kennedy Space Center (KSC) learned this the hard way when the space shuttle program came to an end in 2011 after being judged too costly and unreliable. The local economy cratered. Leadership at the KSC decided to lean into commercial partnerships, and now it is the country’s leading spaceport. Companies like SpaceX, Blue Origin and One Web have invested in large new facilities and hired local workers.

It’s easy to see why Texas lawmakers (nearly all Republicans) are fighting to protect their voters’ government jobs working on ISS. But they may be learning the wrong lesson from KSC. The ISS is quite expensive, and the current administration keeps trying to shut it down by 2024. A future administration may have the clout to actually make that happen; regardless, the ISS will probably be over by the end of the next decade. Will there be a thriving community of commercial space start-ups in Houston to pick up the slack? Or will there just be tumbleweeds?

🌘 🌘 🌘

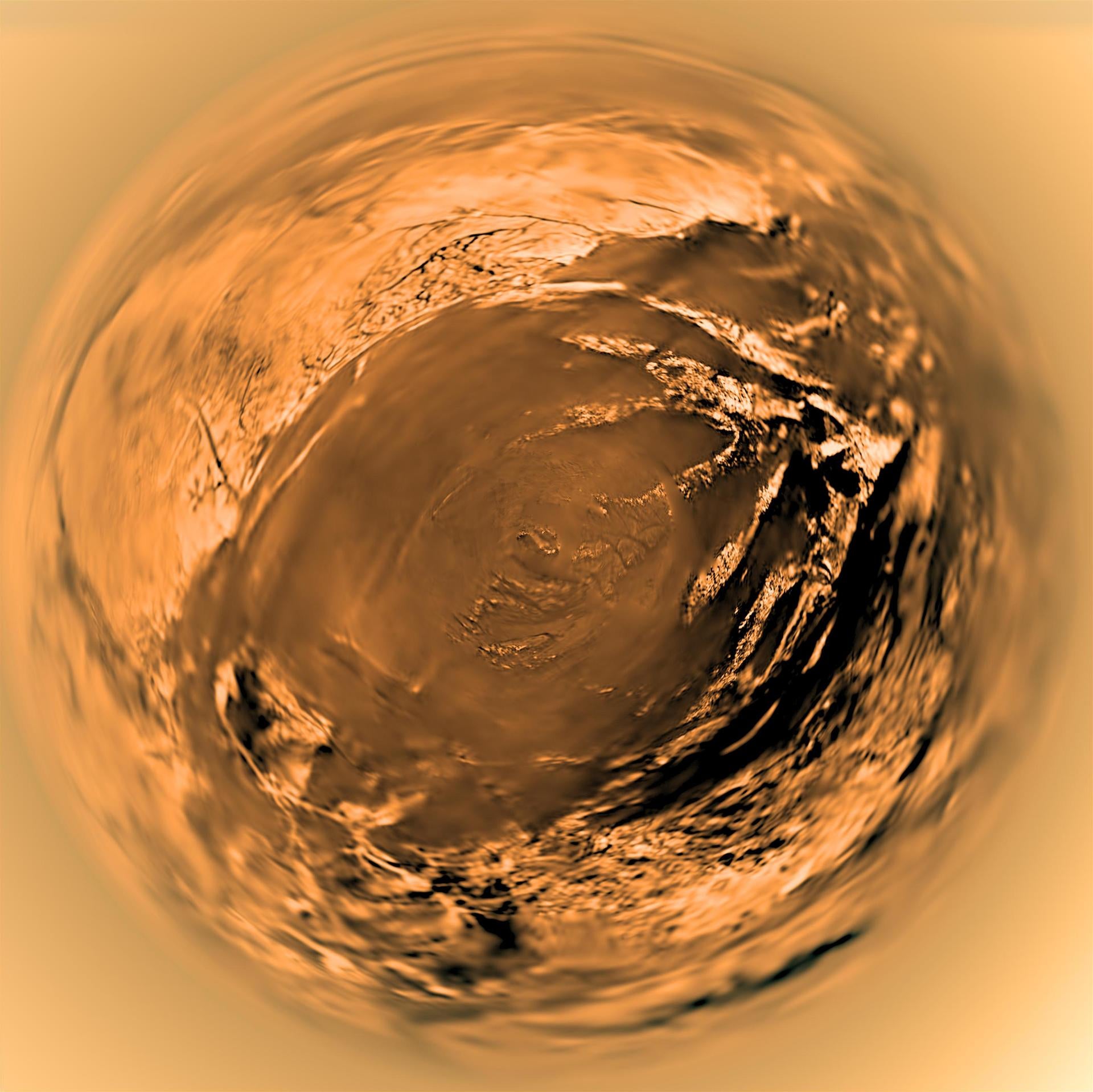

Imagery Interlude: NASA has begun preparing for a new mission to Titan, one of Saturn’s moons. They’re using data gathered by the Cassini-Huygens space probe, which explored Titan, to find the right places to visit. Here’s one fascinating fish-eye lens shot from the last mission:

The agency proposes to send a dronecopter whizzing around to hunt for signs of organic life and clues to the moon’s formation, in a mission scheduled to launch in 2026 and reach Titan by 2034.

🌘 🌘 🌘

SPACE DEBRIS

Asteroid agonistes. NASA said last week that it would not fund a space telescope called NEOCam to hunt for potentially deadly asteroids, even though a National Academy of Sciences report said its infrared sensors are the best way to do the job. The agency apparently won’t act unless Congress funds the project, but it also hasn’t asked for the funds, some $40 million a year. Meanwhile, NASA wants $1.6 billion to re-start its moon mission. Guess which project the public is interested in?

Falcon vs. Pegasus. SpaceX picked up a contract to launch a NASA space mission this week. It’s pretty routine news, except for the footnote that it will cost just over $50 million thanks to a reusable rocket booster. SpaceX was able to beat the alternative, an air-launched rocket called Pegasus that cost $56 million the last time NASA used it. Another signal to the rocket community that price matters—and a reminder that the erstwhile Stratolaunch’s plan to use Pegasus rockets never made business sense.

Stop, drop, and roll. Richard Branson’s other space company, Virgin Orbit, had itself a nice day yesterday with a successful “drop test.” The Los Angeles-based firm plans to launch small rockets from a converted airliner, and a practice flight to see what happens when the vehicle is deployed went swimmingly. The next step will be actually testing the rocket in flight. If the team can get this system operational, it promises to be an effective competitor in the small satellite launch market.

Small satellites to get new rules. The FCC has unveiled a draft of new rules for companies that want to launch small satellites. The news was welcomed by industry officials, since it promises to lower costs and speed up activity; currently, it can cost more to obtain a license to operate a small satellite than it does to launch one. Regulators are trying to keep up with fast-moving start-ups like Swarm, which launched the first satellites without government permission last year. The company paid a $900,000 fine for its troubles, but the new rules suggest that the FCC wants to make it easier for Swarm and other companies like it to keep innovating.

What’s the Buzz? Legendary astronaut Buzz Aldrin has laid out a plan to get the US back to the moon that jibes with everything we know about physics and engineering, and nothing we know about politics.

your pal,

Tim

Hope your week is out of this world. Please send Virgin Galactic’s past financial statements, government job plans, tips and informed opinions to [email protected].