Space Business: NASA's Moment of Truth

The Artemis 1 team faces a tough test flight decision.

Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: Artemis 1 hangs in the balance, Starlink news dump, and arms control in space.

🚀 🚀 🚀

The engineers at NASA saw it coming: Aborted dress rehearsals never gave them a chance to test the procedures for making their Moon rocket’s engines cold enough to launch. Sure enough, they got a bad temperature, and eventually had to shut the show down.

Now, the team in charge of the Artemis 1 test mission faces a difficult choice: They suspect a sensor problem, so they are trying to use other data to figure out the engine’s temperature and launch the rocket. Otherwise, they have to roll the whole thing back to the hangar, pop open the engine, and figure out what’s up. That latter choice could cost the program weeks of time (and commensurate money) that it can’t really spare, but failure isn’t really an option, either.

To be fair, bringing a new rocket to the launchpad is tricky business. Few space vehicle development programs get off the ground without initial failures, scrubbed launches, and re-designs. One somewhat out-of-date US government study has the average rocket program facing 27 months of delay. Even SpaceX has had plenty of trouble with cryogenic propellant. On the other hand, this Space Launch System (SLS) rocket was supposed to launch in 2016 (and 2020).

And then there is the important context of SpaceX’s rocket development. Elon Musk’s company has one deep space rocket, the Falcon Heavy, that could be used for a lunar mission, and is working on the first demonstration of Starship, a massive rocket that NASA wants to use to put astronauts on the lunar surface. If Artemis 1 fails outright, a multi-year wait for the next attempt might make it impossible for lawmakers not to use a cheaper alternative.

Which brings us back to a familiar question: What is SpaceX doing that NASA’s team, including Boeing and Aerojet Rocketdyne, are not? The extremely difficult choice faced by NASA right now is in part the consequence of how the space agency manages its development programs.

This test flight has to succeed because NASA just doesn’t have extra SLS rockets or spacecraft kicking around, and because this rocket can only be loaded and fueled so many times; NASA planned to reserve 13 for this launch. That’s one reason why the space agency chose to head for the launch pad instead of completing a full dress rehearsal. But as former NASA deputy administrator Lori Garver pointed out, “the consequence of two years before another test flight and four years before astronauts could launch, all while other systems progress, make this more than a ‘test flight’ in the usual sense.”

SpaceX, on the other hand, embraces test failures more than most aerospace companies, and plans hardware-rich programs to drive down the cost of those failures on the manufacturing line. Its Starship development program started with a minimum viable product, “the Starhopper” and then saw the Starship vehicle take flight, with more than a few anomalies along the way. A real caveat is that the company still hasn’t flown the massive booster it needs to put Starship in orbit, which is most similar in size and complexity to the SLS, but it is moving much faster than the SLS program did.

Above all, the politics of spaceflight mean NASA needs to show policymakers in Washington that it can deliver, even if those policymakers don’t give them the right resources to do the job. Close observers of the US government’s efforts to build new spacecraft have pointed out again and again that its “failure is not an option” approach to testing (as opposed to operational flights) defeats the purpose of experimentation. Even the Apollo program had more test hardware to play with than the Artemis.

That’s why, even if Artemis 1 gets off the ground this weekend, NASA will need to do things differently next time to avoid a tough choices like the one its team currently faces. Even the most talented engineers (and NASA is full of them) can’t test without testing.

🌕🌖🌗

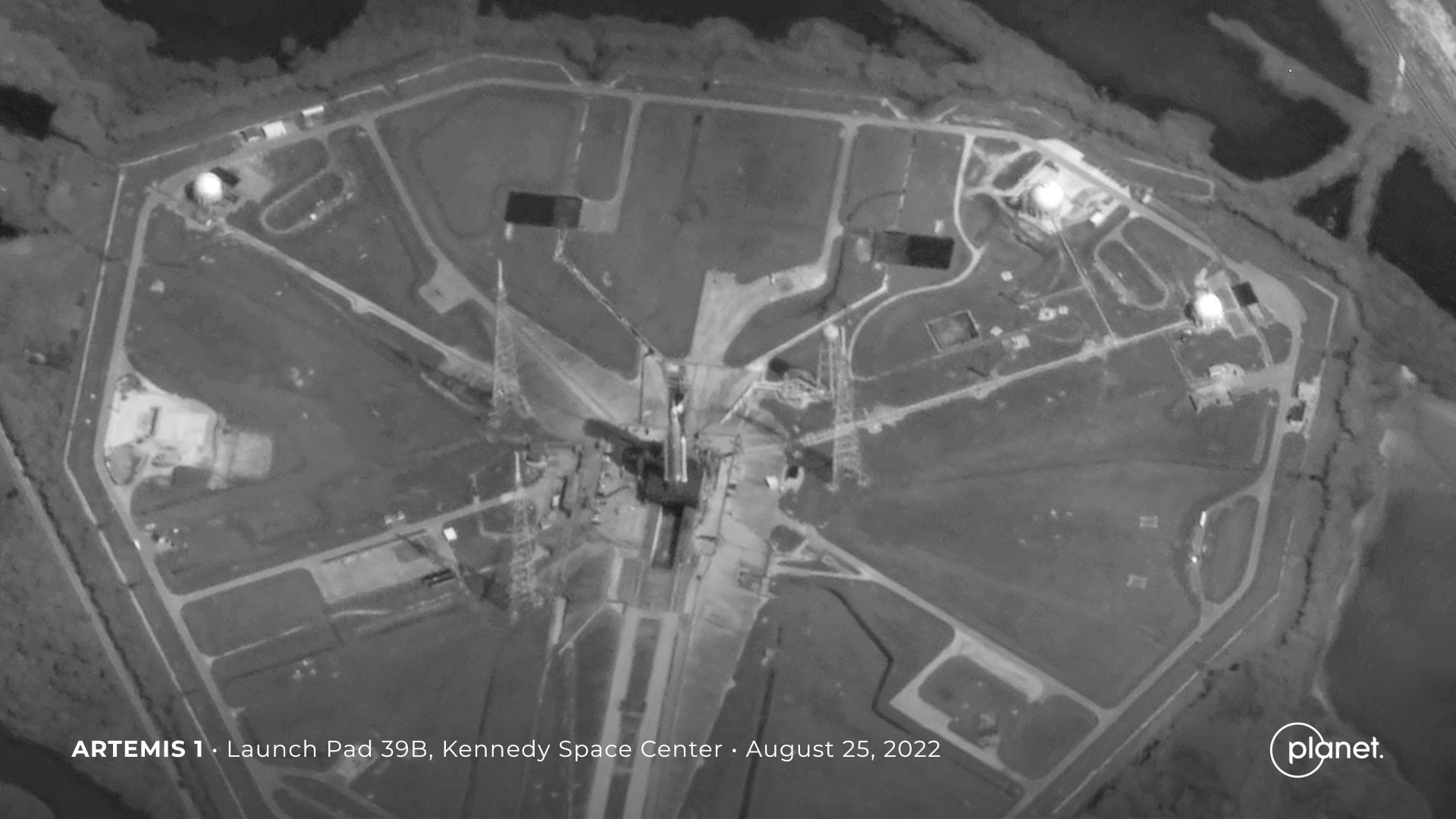

IMAGERY INTERLUDE

While Artemis 1 is waiting on the pad, satellites are flying high overhead. One, operated by Planet, took a video.

You can watch the clip here, and spend some time thinking about how it was taken on a vehicle moving at orbital velocity hundreds of miles above.

🛰🛰🛰

SPACE DEBRIS

Starlink Omnibus. In the last week, the world’s biggest and most controversial satellite network...

- Had a three-hour global outage.

- Announced plans to provide service to Royal Caribbean cruise liners.

- Won a court case against competitor ViaSat, which had demanded the Federal Communications Commission take environmental concerns about Starlink more seriously.

- Announced a partnership with T-Mobile to link up with everyday mobile phones, but technical and regulatory challenges abound.

US lobbies for UN satellite weapons test bans. After issuing a moratorium on destructive anti-satellite weapons tests earlier this year, US diplomats are asking other countries to join in a UN resolution or even a multilateral treaty to make such a policy a global norm.

Axiom will send three paying passengers to the ISS in 2023. The Texas-based space company will make its second private mission to the space station, with three passengers accompanied by a former US astronaut acting as a chaperone, after a successful flight earlier this year.

SpaceX will send five more astronaut crews to the ISS. NASA will pay $1.4 billion, or about $280 million per mission, under the agreement.

The music of the spheres. To understand the life of the space reporter, you must understand the hold music NASA uses for its conference calls.

Satellites tracking crime and toxic algae. The Moon is fun, but what matters in space business right now are how satellites are used here on Earth: Now more than ever, to track illegal fishing and logging that once would have gone on unseen, or spot deadly algae that threatens people and their pets.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 148 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send me your favorite cleansing activities post-launch scrub, the lyrics you’ve written for NASA’s hold music, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].