Space Business: Launch is over

Dear readers,

Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: Vertical integration, Venus in California, and a mystery Chinese space plane.

🌘 🌘 🌘

Time’s up for dozens of nascent rocket companies still seeking to get their vehicles off the ground, from Jeff Bezos’ multi-billion dollar Blue Origin to smaller venture-backed efforts like Relativity Space, Firefly, or Astra, according to Rocket Lab CEO Peter Beck.

“Launch is pretty much a solved problem…If you’re planning to be just a pure-play freight company, that obviously has a ceiling,” he tells Quartz. “Between SpaceX and Rocket Lab with small launch, we have a fair chunk of the market share. If you really want to grow and expand your business, you can either match the growth rate of launch or capture other parts of the space ecosystem.”

Beck’s company staked its claim on the latter in August with the surprise launch of a satellite called First Light. It’s the first example of a spacecraft called Photon, which can be used to deliver customer payloads to bespoke orbits and distant planets, or act as a satellite itself, carrying remote sensors and transceivers to collect data and transmit it back to earth.

This is a move toward vertical integration—no longer simply a transportation company, Rocket Lab will now be involved in building some of the cargo it carries into space. It’s also not a coincidence that the other successful rocket start-up, Elon Musk’s SpaceX, has in recent years expanded its business to building and operating a global satellite communications network called Starlink.

As Beck notes, the math is straightforward. In 2019, per the consultants at Bryce Space and Technology, the global launch industry earned $4.9 billion, while satellite manufacturers earned $12.5 billion and satellite network operators garnered $123 billion. If you want to build a city on Mars, or simply deliver growth to your venture investors, you need to head up the value chain.

“I’m surprised people didn’t pick it up earlier,” Beck says, noting the company’s March 2020 acquisition of Sinclair Space Systems, which builds satellite components.

Guilty as charged: In an interview with that firm’s founder, Doug Sinclair, after the acquisition, I didn’t pay enough attention to his comments expressing admiration for the Agena, a spacecraft once used by the US government as a platform for technology development in low-earth orbit. “You would just bolt your payload to that,” Sinclair explained, adding he was excited to try and do similar work on the scale enabled by modern electronics. (I did not forget Rocket Lab’s real “first” satellite, the somewhat controversial “Humanity Star.”)

Skeptics will note that there is an aspect of pump-priming to these programs, ensuring there is cargo for the main launch business. For SpaceX, 10 of the company’s sixteen flights this year were launching its own Starlink satellites. Beck, who says his company’s projections for satellite cargos were conservative and largely fulfilled, hopes the Photon platform will enable start-ups to begin using space-based tools more quickly, generating new opportunities for his rockets.

The two companies are taking very different strategies: SpaceX’s ambitious communications network appears poised to compete directly against major internet service providers, while Rocket Lab’s focus is on expanding the options it can offer new and existing customers seeking to use satellites in their businesses. Tim Farrar, a satellite industry consultant, says both firms can take advantage of the rapid experimentation that comes with operating their own rockets, but from there, prospects diverge.

“SpaceX needs to show a very large amount of revenue to justify what it’s already done, let alone if they are going to keep making hundreds of satellites a month on an ongoing basis,” Farrar says. For Rocket Lab’s offering of a generic platform suitable for different kinds of space activities, success will depend on whether the cheaper Photon can offer enough capability to replace a purpose-built spacecraft, he adds.

Beck sees the new initiative as part of the broader goal shared by all these firms—lowering the cost of doing business in space.

“How do you affordably get a business or an idea into orbit?” Beck asks. “That’s the bit that Photon aims to try and solve. If your rocket is your satellite and your satellite is your rocket, you just come with an idea.”

🌘 🌘 🌘

IMAGERY INTERLUDE

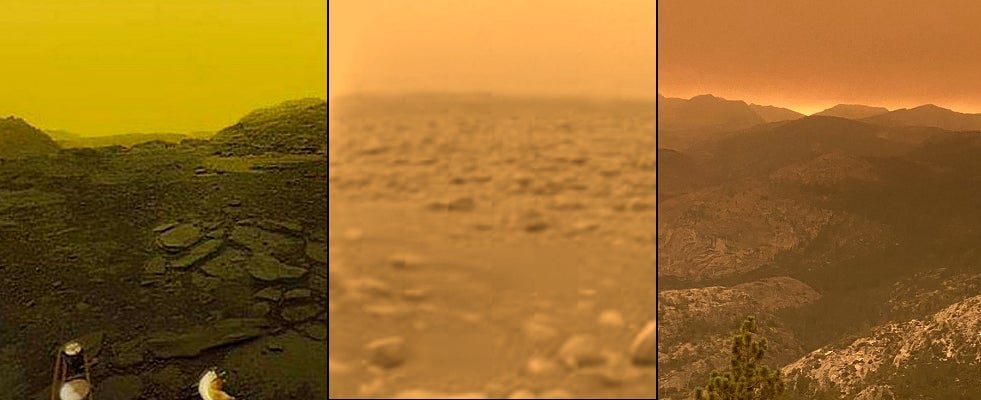

I awoke yesterday morning in Oakland, California, to a dismal orange glow that would suffuse the sky for the entire “day.” The dystopian pictures emerging from across the US west coast were the result of massive wildfires spurred on by climate change. Space scientists were struck by the similarity of earthly conditions to images captured on distant worlds. Paul Byrne, a planetary scientist, and Katie Mack, a cosmologist, wondered on Twitter whether conditions were more similar to Venus or Jupiter’s moon Titan. Byrne assembled this triptych for comparison purposes:

On the far left, Venus imagery from the Soviet Venera 13 lander; in the middle, a scene on Titan captured by the Huygens probe; and on the right, a picture of Yosemite National Park snapped by Twitter user TheAdveturizr.

The physics at play is the scattering of light by particles in the atmosphere, but the impact is the shock, in Byrne’s words, “that wildfires can have such a pronounced effect on something we take for granted—the colour of the sky.”

👀 Read this 👀

When Robert Hallett was a kid, he wanted to be an astronaut. Everybody did—it was the 1960s.

Of course, our childhood dreams don’t always crystallize into reality. One recent survey found that only 10% of American adults held their childhood dream jobs. Would-be actors decide to prioritize financial security. Aspiring doctors have the wind taken out of their sails in a tough organic chemistry class. And some decide, as Hallet did, that a childhood aspiration of flying to the moon just isn’t realistic.

The road not taken—so-called “regrets of inaction”—tend to stick and have an impact on our mental health. This doesn’t mean that those of us who feel we’ve made professional mistakes are doomed to keep ruminating about lost opportunities forever. Read how we can take control of our own narrative back, and how Hallett did it, in our field guide on decision making.

🛰🛰🛰

SPACE DEBRIS

China Space Plane? China announced that it had launched and recovered a “reusable experimental spacecraft” last week. If so, that’s another big step forward for the country’s space program. US and independent analysts suspect the vehicle is similar to the US X-37B, an autonomous spacecraft that looks like a tiny space shuttle and has a geopolitical purpose of its own. While we don’t have any clear imagery of the vehicle, one clue to its design is that it appears to have landed at an enormous runway. The design of the runway is matched by just a few places in the world, according to NPR correspondent Geoff Brumfiel—the huge landing strips intended to welcome home US and Russian space planes.

Annals of Fantastic Propulsion. The problem with rockets that use chemical propellants is that they are too limited by fuel needs and efficiency to allow for exploration beyond the solar system, if that’s your sort of thing. There’s no warp drive or hyperspace available to carry humans past the speed of light. But a small number of experimenters believe that exploiting a wrinkle in the theory of relativity could allow a new kind of electrical propulsion in space, capable of carrying a vehicle to a distant star within a human lifetime. Mainstream physicists disagree—strongly—but that hasn’t stopped a new round of experiments from attempting to validate the idea.

China’s Landspace raises $175 million. A leading small rocket company in China, Landspace, raised $175 million from a group of venture investors. Its backers include US venture firm Sequoia’s Chinese office. Notably, its parent firm infamously pulled the plug on Vector, one of the first post-SpaceX small rocket start-ups. As Peter Beck said above, launch is arguably a solved problem, but it’s also a geopolitically defined one—the US may not need another private small launcher, but China’s nascent space industry can still support a national champion.

NOmegA. No surprise here that Northrop Grumman announced it will not be building its OmegA rocket after failing to win a key military contract. The rocket, based around legacy solid-fuel rocket boosters, never really made sense as a technological competitor for liquid-fueled rockets operated by SpaceX and United Launch Alliance.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 64 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your apocalyptic visions of the Great Filter, Chinese space venture investment strategies, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].