Space Business: Ad Busters

Dear readers,

Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: NASA’s economic impact, a model astronaut, and the case for spatial distancing.

🚀 🚀 🚀

The push for commercial activity onboard the International Space Station, notably a plan to film an advertisement for cosmetics giant Estée Lauder, has been met with fears that NASA is shifting too far from its science agenda.

“Some people were surprised when NASA was supporting a marketing initiative on the ISS,” Phil McAlister, the agency’s director of commercial spaceflight, said last week. “That’s exactly why we think this is a good project to perform on the ISS. We need to expand people’s perspective on what we can accomplish in space on the ISS.”

It’s worth remembering that the law that governs NASA prioritizes “the fullest commercial use of space” over the “expansion of human knowledge of the Earth and of phenomena in the atmosphere and space.”

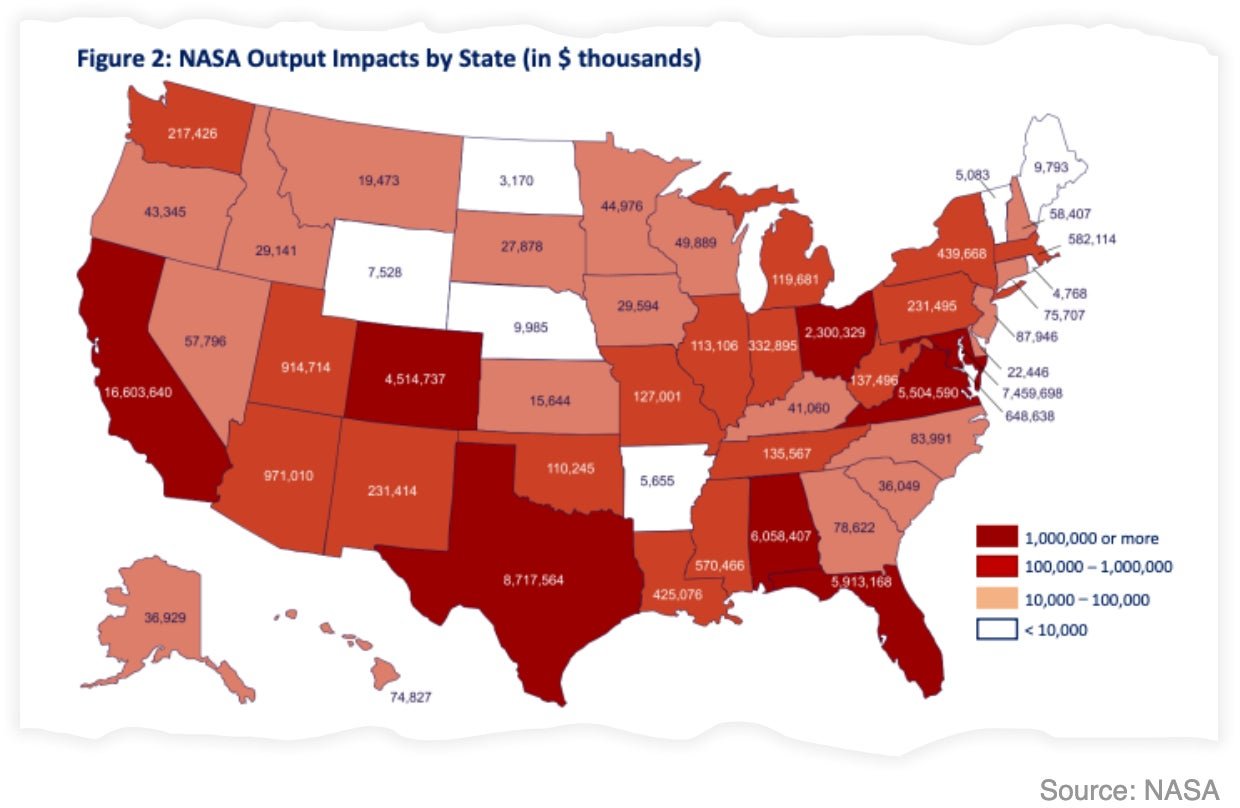

That may be legal pedantry, but for a more concrete example, consult NASA’s 2019 economic impact study (pdf), which argues that the space agency sustains 312,630 jobs across the US, including the civil servants, contractors, and the jobs generated indirectly by its spending. The report includes this helpful chart showing the economic impacts of NASA’s work on a state by state level:

You can see why senators care so deeply about NASA facilities in their states. The report also emphasizes that NASA’s “moon to Mars” work—a somewhat arbitrary accounting bucket that includes the mooted Artemis return of humans to the moon—has had the greatest economic impact. That may help to convince reluctant lawmakers to pony up the $28 billion needed to make the missions happen.

But a lot of that impact has to do with waste, too: Artemis is one of NASA’s most over-budget programs, including hundreds of millions of dollars in incentive payments that government auditors say shouldn’t have been given to contractors like Boeing and Lockheed Martin as they failed to deliver their products on time.

It puts the subsidized cost of the Estée Lauder mission in perspective—the make-up company will pay $128,000 for services that will probably cost the space agency in the range of $250,000, depending on how you allocate the opportunity cost of astronaut time. That difference isn’t even a rounding error in NASA’s traditional programs.

So why the controversy? It’s not that this is necessarily new or because advertising is seen as a disreputable—Hilton hotels baked cookies on the ISS last year for a marketing stunt, and Pizza Hut delivered in 2001.

The Estée Lauder experiment received the most negative attention because the arrival of private space transport means business in low-earth orbit is becoming less a fever dream of entrepreneurs and more often reality. Yesterday, NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine said the agency would be starting a program to support private astronauts who want to pay to go to the ISS, referencing reports of a Hollywood blockbuster with Tom Cruise attached.

If you’re attached to Star Trek science fiction visions of space exploration where commerce is conveniently elided, this may seem lame, but real people can’t just assume a post-scarcity future. The US space program is divided between those who expect that the space-industrial complex will continue to roll slowly on indefinitely, and those—like Bridenstine and McAllister—who fear a future when lawmakers won’t pony up billions to support the space program.

“It’s not possible for the ISS to operate indefinitely,” McAlister said. “There is going to come a time for the ISS to retire. In order for other destinations to be sustainable, they are going to need customers other than NASA to support their operations.”

🌘 🌘 🌘

IMAGERY INTERLUDE

Preparations are underway for Crew-1, the first “operational” flight of SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft. Dubbed “Resilience,” it will carry four astronauts to the International Space Station in October. The crew includes Americans Shannon Walker, Victor Glover, Michael Hopkins, and Japan’s Soichi Noguchi. Becoming an astronaut inevitably involves posing in a space suit, and while some lean towards a stoic mien, Noguchi, a veteran of two previous space missions, is giving me life by looking like he is excited about his job, which, again, is space travel.

👀 Read this 👀

Emily Nelson is a deputy chief flight director at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, a 20-year veteran of International Space Station operations. When on duty at Mission Control, Nelson is in constant contact with her peers at space station agencies in Munich, Tokyo, and Moscow.

In space exploration, math is a common language, as are scientific principles. But the way those principles are interpreted into engineering practice is different across countries. “Just because their [design] is different from ours doesn’t mean it’s not as good,” she says. “It just means it can take us a while to understand why they want to do something, because their engineering practice guides them to go in a different path than ours would.”

As we navigate the shift to remote work, what can we learn from teams that are built to overcome—and even harness—massive geographic spans and cultural differences to do their work? Read more in our latest field guide.

🛰🛰🛰

Spacial Distancing. Responding to the coronavirus pandemic means facing challenges common to many collective action problems, like climate change—or space debris. Mike Lindsay, the CTO of Astroscale, a company developing technology to remove space debris, outlines the parallels between fighting the virus and fighting space junk.

It fights wildfires! It finds lost children! The prospects of massive new satellite networks in low-earth orbit are bullish, with firms like Northern Sky Research predicting a $68 billion revenue opportunity. We’re only just starting to find out the ways in which that will play out. Connectivity was an obvious solution, and now SpaceX’s Starlink is proving itself by linking up firefighters in Washington state. More remarkable is new research backed by the US Army that suggests Starlink could be a useful navigation service—surely something the UK government will look at as it pulls OneWeb out of bankruptcy to be a national satellite champion.

SETI on the moon. Much of the case for a lunar return hinges on the alluring potential of water on the moon, but there are other mysteries to solve. In particular, a radio telescope on the far side of the moon could give scientists access to important new data, and help drive the search for intelligent life.

SpaceX loses USAF challenge. SpaceX lost its legal challenge to the preliminary phase of a US Air Force contract, according to a federal court ruling spotted by Reuters before it was sealed from public view by the judge. The case revolved around development funding awarded to SpaceX competitors ahead of a final selection of two rocket makers to fly national security satellites in the years ahead.

SpaceX had argued that the US Air Force should have given it funding to develop its Starship vehicle, making the final competition fairer. The judge apparently agreed with the USAF assessment that Starship was too premature to fund, and the lack of additional support didn’t prevent SpaceX from winning a share of the final launch contracts.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 67 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your favorite pictures of astronauts mugging for the cameras, novel NGSO satellite applications, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].