Hello? This is space calling.

Dear readers,

Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: LEO on the line, space toilet news, and Blue Origin’s Orbital Reef.

🚀 🚀 🚀

After you’ve spent a few billion dollars putting tens of thousands of internet-connected computers in space, what do you do with them?

One answer for the companies building mega satellite constellations in low-Earth orbit—SpaceX, OneWeb, Amazon, and others—is to offer broadband service directly to consumers. That’s the approach SpaceX’s Starlink is taking thus far; it has rolled out beta service to hundreds of thousands of users by selling them their own ground terminals.

The benefits? There’s no middleman, the company has total control of the system, and if like Elon Musk you have a global fan base, they’ll line up to take part. The drawbacks? The terminals are expensive to design and produce, and they expose users to the tricky parts of satellite communication, like making sure your antenna has a clear view of the sky and not a tree or nearby building.

An alternative to dealing with all those customers is plugging the satellites directly into an existing terrestrial communications network. If satellites can connect directly to mobile phone networks—or mobile phones themselves—they will not have to worry about developing expensive ground infrastructure or customer services.

This week, Amazon and Verizon said they are working together to link the former’s future Kuiper satellite network and the latter’s mobile service. Amazon’s satellites would provide “backhaul” connections—links to the internet at large—for Verizon cell towers, allowing them to serve their mobile users without adding more wired network connections.

The extra capacity is likely needed: Ericsson, the networking company, forecasts that smartphone users in the US will consume 48 gigabytes of data monthly in 2026, compared to 11 gigabytes last year.

If the two companies put this partnership into effect, it could be vital for Kuiper, which will become operational several years after Starlink, and OneWeb, which is expected to begin offering service before the end of 2021 and has a similar partnership with AT&T. If early adopters go for these other services, working with Verizon could provide immediate revenue, even if it might not be as profitable as a direct relationship.

What about linking modern mobile phones directly to satellite networks? The distances involved mean phones that connect with traditional satellite networks, like those available from Iridium, are bulkier and more expensive than cellular phones, and their data plans are much more costly. They make sense for people in extreme situations, but it’s not an obvious consumer market.

Still, some space companies are betting on plugging right into your iPhone. AST SpaceMobile, which went public this year, wants to solve the connection challenge with enormous antennas in space—which could do the job, but the size of the spacecraft prompted worries from NASA, and the company has yet to receive an operating license. Should they gain regulatory approval, the firm expects to work with Vodafone and other mobile firms to provide connectivity outside the range of cell towers.

Another firm, Lynk, said it has been able to connect mobile phones to a small satellite it launched into space last year, allowing users without cell service to send and receive text messages. It was a significant technical achievement to “fool” the phones into seeing the satellite as mobile towers, but the limited bandwidth available for users shows how tricky the business could be.

There’s also a middle ground. Kymeta, a manufacturer of satellite ground systems, said this week that it had demonstrated the technology to create local LTE networks using terminals connected to satellites as a way to provide connectivity to mobile users out of reach of cell towers. Imagine, for example, first responders battling a wildfire in the wilderness—with a Kymeta terminal on hand, arriving firefighters could use devices they already have to instantly coordinate.

“There is strong community within the satellite environment that is working…basically to drive satellite as just another network option for connectivity,” Neville Meijers, Kymeta’s chief strategy officer, told Quartz. “4G, 5G, you’ll have satellite, a non-terrestrial network, and all these networks will become interconnected in a way that is completely seamless to a customer.”

With the demand for connectivity showing no sign of slacking, satellite operators are poised to deliver capacity that users back on Earth need. But those users might not even know that their calls, texts, and social media posts are being transported through space.

🌘 🌘 🌘

Imagery interlude

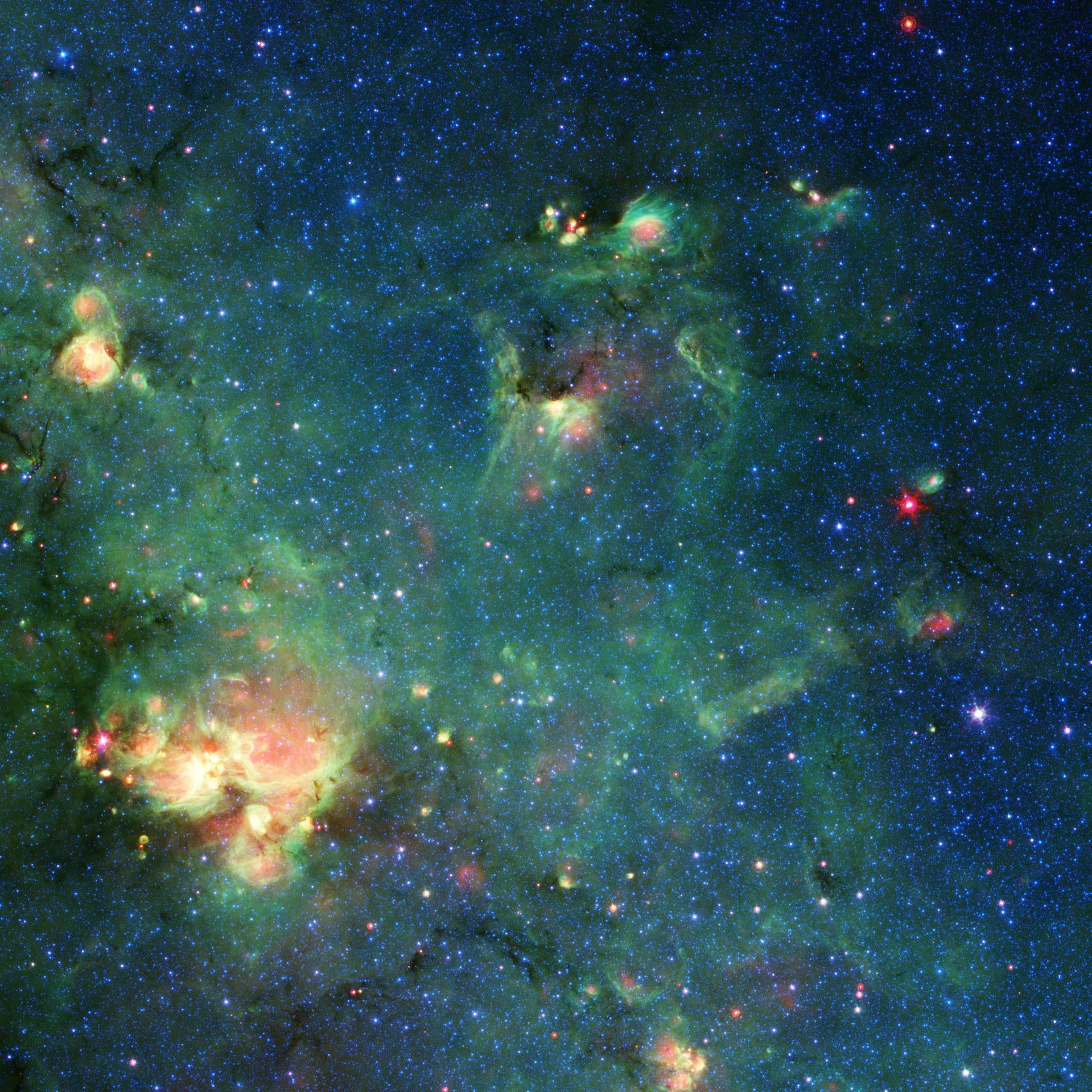

Can you discern a giant radioactive lizard in this image of space 7,800 light-years away from Earth? (Hint: Look for eyes and a snout in the upper right.)

If you can make out Godzilla, well, you’re on the same page as the astronomers working with the Spitzer Space Telescope, an infrared observatory that retired last year after 17 years of service. Its data still proves useful to scientists, and stunning to stargazers.

🌍🌎🌏

This year’s UN climate conference starts on Monday. It’s the biggest summit since the Paris Agreement was inked in 2015. The 26th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the UN’s climate goals comes at a pivotal moment for countries and companies hoping to accelerate their transition to a fossil-fuel-free economy. Quartz will be on the ground in Glasgow, Scotland to track the announcements and behind-the-scenes talks. Follow along by subscribing to our free Need to Know: COP26 newsletter.

🛰🛰🛰

Space debris

The number one problem. The passengers who spent three days in orbit onboard SpaceX’s Dragon capsule gave us some hints that something had gone awry with the toilet. Now, ahead of this weekend’s launch of four US astronauts to the ISS on a vehicle of the same design, SpaceX officials revealed that urine leaked behind panels in the spacecraft. After on-orbit inspections and experiments on the ground, officials say the latest in a long line of space toilet troubles has been resolved.

Reefer Madness. Blue Origin, Sierra Space, and Boeing said they would team up to develop a space station for low-Earth orbit. While executives declined to say what kind of financing they had secured, the “Orbital Reef” will compete to win business hosting payloads and research for NASA. One of Blue’s space architects said later that Orbital Reef is “the first achievable urban concept for LEO.”

More money for small rockets. ABL Space Systems, a launch vehicle start-up, raised $200 million toward the development of its RS1 rocket. ABL has yet to demonstrate it can put a satellite on orbit, but has won a 58 launch contract from one of its investors, Lockheed Martin.

Woz Watch. Apple legend Steve Wozniak has hired Moribah Jah, a leading expert on space debris at the University of Texas, Austin, as the chief scientific adviser for Privateer, a startup dedicated to addressing the problem of orbital trash. The company plans to fly its first satellite in early 2022.

Top 40. China set a new national record this week with its 40th orbital launch of the year. The national world record belongs to the Soviet Union, which launched 101 orbital rockets in 1982; the US hit its peak in 1966 when it launched 73 rockets.

your pal,

Tim

This was issue 113 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your strategies for monetizing NGSO constellations, takes on private habitats in Earth orbit, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].