NASA scientists have created a new framework to ask if alien life exists

Dear readers,

Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let us know what you think. This week, via science writer Sarah Scoles: screening space signals and errant debris.

🚀 🚀 🚀

The Allan Hills meteorite has had a long and storied life: It solidified from molten Mars rock billions of years ago, shot into space millions of years ago, fell to Antarctica thousands of years ago, was discovered in 1984, and made headlines in 1996. That summer, scientists announced that its structure and chemistry suggested evidence of past life on Mars: ancient aliens. Bill Clinton even made a speech about it. In response, other researchers attempted to show how the meteorite’s strangeness could be the result of things like geologic forces and chemical processes—not biology. Their conclusion remains the consensus today.

But the authors of a recent Nature paper suggest that this dichotomous formulation—Yes, aliens! No, refutation—misses important gray: that scientists could better accept, investigate, communicate, and learn from the very liminality of such discoveries.

Things might have gone down differently if scientists had been using the new “Confidence of Life Detection” scale, laid out in that Nature paper by six NASA scientists. The “CoLD” scale attempts to capture and quantify the uncertainty inherent to astrobiology, rather than framing research as “Are we alone? Y/N.”

Accepting that potential evidence of alien biology is almost necessarily gray can motivate scientists to seek more associated evidence, and move the discovery along the CoLD scale’s seven proposed levels.

A level 1 discovery means a scientist found a signal known to result from biological activity. To move up a slot, researchers would have to rule out signal contamination. At level 3, they need a working explanation for how life could make such a signal in its home environment. A tall order comes before level 4: Non-biological ways of making the signal should be excluded as possibilities. Level 5 requires another, independent data point from the hypothetical biology, while Level 6 demands the rejection of any possible alternative explanations that may have emerged after the initial discovery. Lucky level number 7 requires independent follow-up observations—and maybe even a life-seeking space mission. The Allan Hills meteorite would net a 3, the new paper estimates.

The levels take their inspiration partly from the Torino scale, which communicates via color scheme (red = scary, green = go about your business) how hazardous a potential asteroid or comet impact is. They’re also modeled after NASA’s “Technology Readiness Levels,” which categorize space technology from its inception as a fuzzy concept (1) to its successful flight on a mission (9).

CoLD levels are more useful than yeas or nays because almost any future “yea” is likely to begin as a “well, maybe,” unless we find a sneaky Martian elephant species. Geochemical or atmospheric processes can mimic microbes. And separating the physical from the biological isn’t simple—especially if the hypothetical life is very different from that of Earth. The aha moment also might happen on a planet humans have never tapped directly, or a distant exo-world we almost certainly never will. Having a quantification for that uncertainty, and a way for it to evolve, could help scientists and the public keep track of progress without swinging toward hype or dismissal.

SETI scientists—who look not for direct evidence of alien biology but for evidence of alien technology—created a similar scale for their efforts around 20 years ago, even though their data are likely to be less ambiguous. The “Rio Scale” gives potential “technosignatures” a score from 0 to 10, based on how consequential the hello would be if it were real, and how credible it is.

When a wowing signal from space hits the news, though, an associated Rio score rarely does. A 2019 paper in the International Journal of Astrobiology, proposing a slightly revised Rio 2.0, suggests the lack of “brand recognition” is in part because maybe-aliens stories break fast and go viral, while scientists themselves don’t often proclaim Rio scores. Straightforward, transparent calculators built with modern web tools aren’t widely available, and the actual calculation is a bit opaque, meaning the public is less likely to go out and tabulate their own Rio numbers.

If the CoLD scale is to become hot, astrobiologists would do well to consider the ideas the Rio revision team suggested: Attach a score to each potential discovery immediately, ideally along with the press release; include scores from independent experts with no skin in the game; give people a mobile-friendly way to do their own calculation; and keep updating the number as evidence flows in.

The CoLD creators stress that they don’t need their framework to be the one that ultimately rules the cosmos. It’s supposed to spur conversations about what life detection might look like, and how to realistically convey that to research-doing, news-consuming earthlings. Maybe, then, Bill Clinton was right back in 1996. “Even as it promises answers to some of our oldest questions,” he said of the meteorite, “it poses still others even more fundamental.” Like how to live without easy answers to those questions.

Your pal,

Sarah

🌘 🌘 🌘

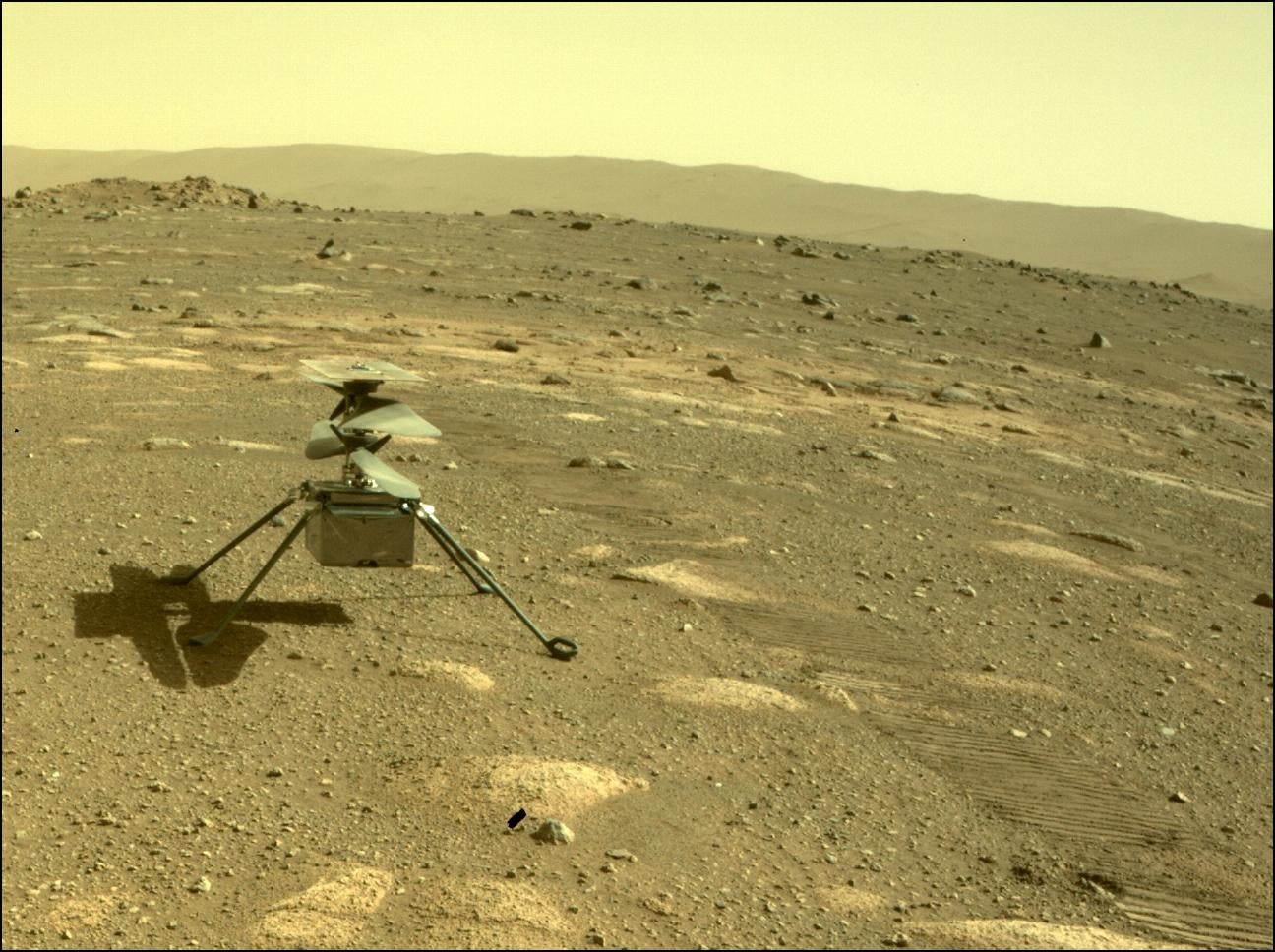

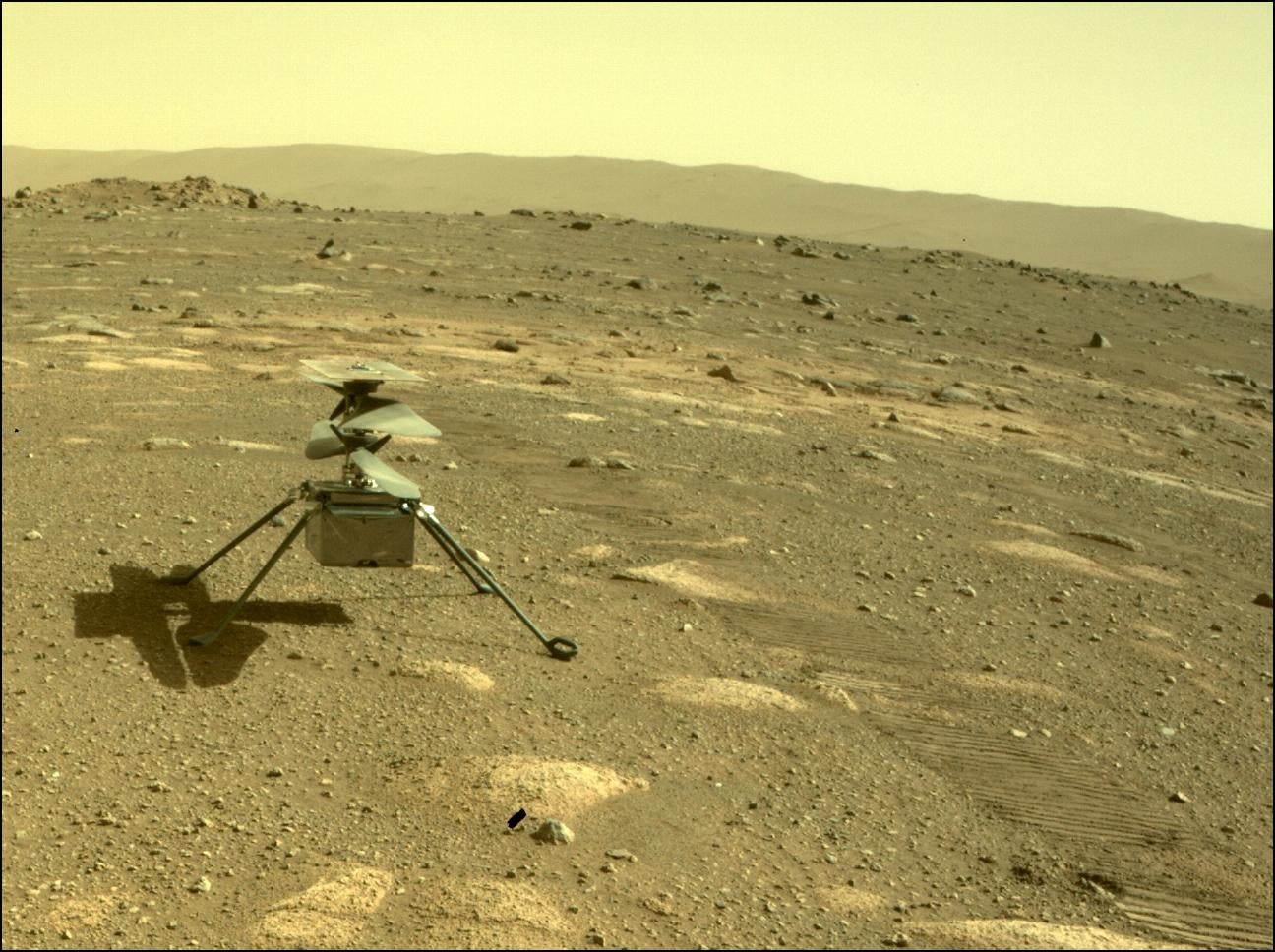

Imagery interlude

NASA cleared astronauts Thomas Marshburn and Kayla Barron to go on a spacewalk to conduct repairs on the International Space Station on Dec. 2. The outing had originally been scheduled for earlier in the week, but the space agency canceled it last-minute to avoid potential space junk. Hundreds of pieces of debris disrupted life at the ISS after Russia blew up a satellite during a missile test in mid-November.

Here are Marshburn, Barron, and Matthias Maurer, a European Space Agency astronaut, preparing for the mission.

🌍🌎🌏

Start your day right—and that includes your first bleary-eyed scroll through the inbox. Improve your awakening by signing up for Quartz’s Daily Brief, an efficient and enlightened guide to the news of the day.

🛰🛰🛰

Space Business writer Tim Fernholz is on leave. He’ll be back in 2022.

This was issue 116 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send Martian elephants, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].