NASA’s new space telescope is 14 years late and 1000% over budget

Dear readers,

Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let us know what you think. This week, via author David W. Brown: astronomical budgets and space X-rays.

🚀 🚀 🚀

In less than two weeks, the European Space Agency will launch NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope. If all goes as planned, the days that follow will see the telescope transform from its boxy launch configuration into something resembling an Imperial Star Destroyer. Six months later, it will begin peering 13.5 billion years into the past, and give humankind a glimpse of the first stars and galaxies ever to form.

If all goes as planned.

Unlike the Hubble Space Telescope, JWST will not orbit the Earth. Rather, it will be placed at a stable gravitational spot in space called Lagrange Point 2, which is 932,000 miles beyond Earth relative to the Sun, and one of the few accessible places cold enough for the infrared telescope to operate properly. This is about three times the distance of the Moon from the Earth, which means if something goes wrong, there is nothing anyone can do to fix it. It will be as useful to astronomers as Elon Musk’s red, spacefaring Tesla.

Success is not assured, given the troubled development of JWST, which includes screws and washers falling off the thing and a “sudden, unplanned release” last month of a clamp band that keeps it attached to the rocket during launch. Failure would set back astronomy by decades—and it almost happened once before.

After the Hubble Space Telescope launched in 1990, wide-eyed scientists waited to see what wonders of the cosmos it might reveal, but when the first data came down, something was terribly wrong. The images were blurry—the main thing telescope images are not supposed to be.

Consequently, NASA and the telescope sustained years of ridicule. It was a late-night talk show punchline. Bumper stickers appeared on cars: “If you can read this you are not the Hubble Space Telescope.”

Engineers soon discovered that Hubble’s mirror was flawless, but to the wrong specification. As such, they could build eyeglasses for the telescope, which they did, and in 1993, astronauts from the shuttle Endeavor repaired the beleaguered Hubble. The telescope is still paying dividends.

JWST, Hubble’s successor, is late and over budget. When conceived in 1996, some of the best minds in astronomy from across government and academia came together and determined (pdf) that it could be built for $500 million and launched in 2007. Adjusted for inflation, that’s about $881 million.

In the end, the telescope cost $8.8 billion (plus another billion dollars to operate.)

Last month, unabashed by the 1000% budgeting error and fourteen-year delay, astronomers met and endorsed the next giant telescope they want taxpayers to fund. This one, they said, could be built for $11 billion and launch in the 2040s. History suggests that these numbers are unreliable at best—and also that astronomers aren’t worried about it.

Today, few remember the three years of mockery that followed the launch of Hubble, or that it was three times more expensive than planned. We remember only the telescope’s profound and ongoing successes. NASA and aerospace contractors are counting on this.

Internally at NASA, this is called “Hubble psychology” (pdf.) Project managers know precisely how wondrous and spectacular their missions tend to be. Excessive “optimism” regarding cost and schedule is thus incentivized. By the time reality sets in, it is too late to turn back, and budgets go haywire.

When the James Webb Space Telescope launches, assuming it works, our astrophysical understanding of the universe might be changed forever. Undoubtedly, the things it sees will mesmerize and inspire generations of school children and adults alike, and appear on textbook covers and computer desktop backgrounds. No one will remember the cost, management, and technical problems that plagued it.

But they should. While the value of astronomy is infinite, the money available to pay for it is not. When space telescopes go over budget, the US government does not take a hard look at the national budget and cancel a few fighter jets to cover the shortfall. Rather, they cancel, delay, or ignore other science missions.

Soon, we may know what the universe was like in the very distant past. But only by learning the lessons of the James Webb Space Telescope’s development can NASA ensure a balanced, robust science portfolio into the future.

Your pal,

David

🌘 🌘 🌘

Imagery interlude

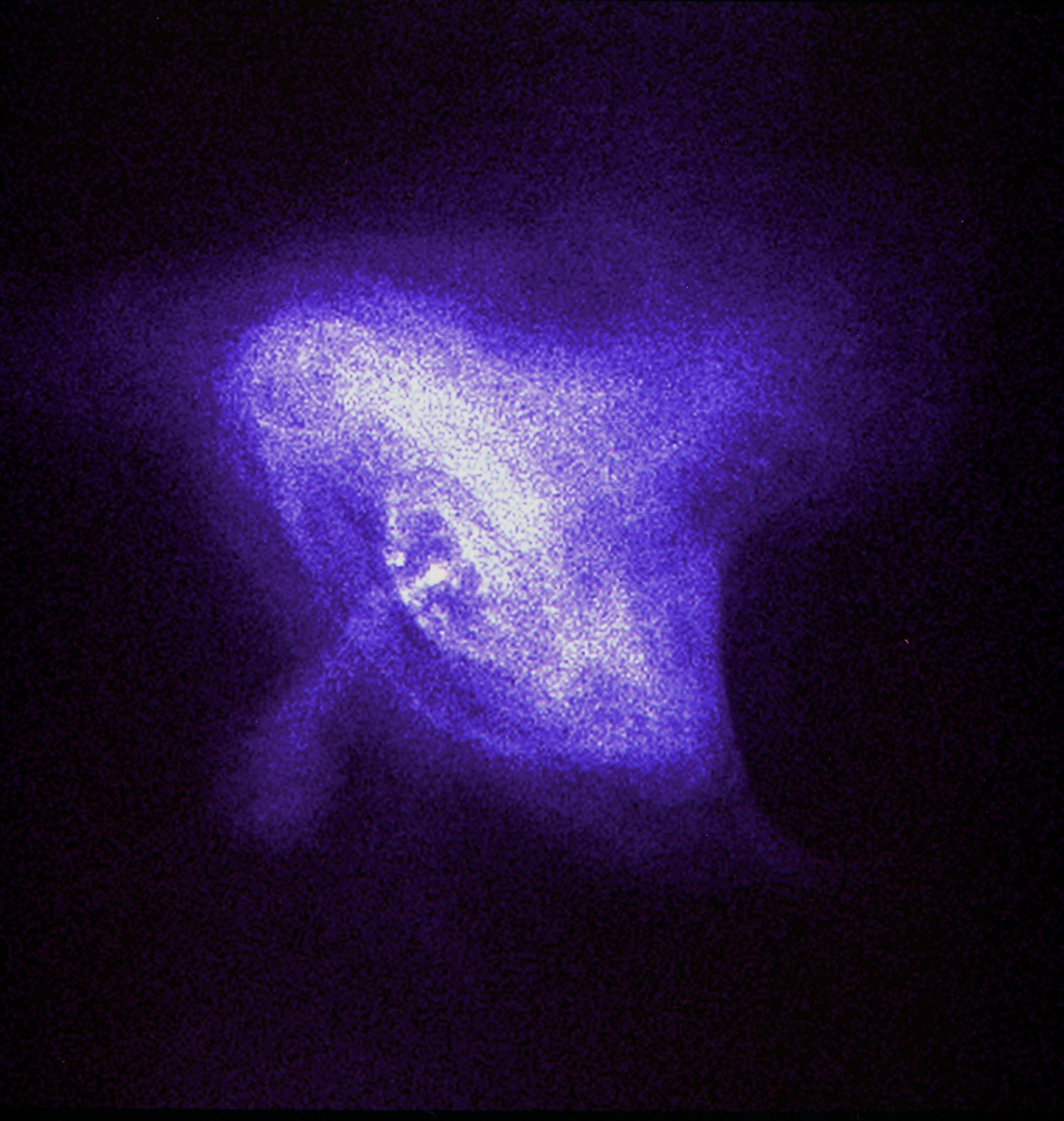

NASA was scheduled to launch another space telescope Dec. 9. The Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer, or IXPE, will scan X-rays from black holes and neutron stars that could shed light on how the universe works. Here’s an image of the Crab Nebula, taken in 1999 by another X-ray telescope, the Chandra X-ray Observatory.

IXPE will also be targeting Crab, but unlike Chandra, it will capture polarization, which can tell scientists where light comes from and what it passes through. “We’re going to spend all of our time looking at the bright sources and trying to measure the polarization for the first time,” Martin Weisskopf, IXPE’s lead researcher, told NASA’s podcast Gravity Assist. “And confound the theorists.”

🌍🌎🌏

Start your day right—and that includes your first bleary-eyed scroll through the inbox. Improve your awakening by signing up for Quartz’s Daily Brief, an efficient and enlightened guide to the news of the day.

🛰🛰🛰

Space Business writer Tim Fernholz is on leave. He’ll be back in 2022.

This was issue 117 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send Crab pictures, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].