Why Latin America needs its own space agency

Dear readers,

Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere, this time hosted by Ana Campoy, Quartz’s deputy finance and economics editor. Please forward widely, and let us know what you think. This week: an agency of one’s own and Hunga speaks.

🚀 🚀 🚀

After decades of talk, Latin America is the closest it’s been to launching a regional space agency.

Last autumn, 18 countries, including Mexico and Argentina, signed an agreement (pdf, Spanish) to create the Latin American and Caribbean Space Agency, or ALCE. It’s unclear whether those plans will materialize into a viable operation that regularly shoots satellites into space, never mind rockets or astronauts. But the accord’s mere existence is already giving the region’s emerging space industry a much needed push.

Latin America has never been a space power, but there was a time when it could hold its own. In 1967, Argentina was the fourth country to launch an animal into space, a mouse named Belisario. A year later, Mexico beamed up the 1968 Olympic Games via the Tulancingo satellite ground station (Spanish), at one time among the largest of its kind.

After a decades-long lull, space activity has more recently picked up as the private sector jumps in. Progress so far is unevenly spread, with a burst of projects in some countries while nothing happens in others. A regional space agency might be what the industry needs to gel, or at least that’s the hope of Latin American space industry advocates. They point to the European Space Agency (ESA) as a model of how regional cooperation can propel the private space industry.

“A lot of investment and activities in the countries that are part of that space agency were very much driven by the creation of the agency,” said Luciano Giesso, an executive at Earth observation firm Satellogic, which was started by Argentines.

For starters, they see ALCE as a client for their products and services. Among the agency’s most concrete goals, per the agreement: building up Earth observation systems and satellite communication.

ALCE also could pave the way for international missions and bolster local entrepreneurs as they venture into business with bigger, more established companies. The backing of Mexico’s space agency, AEM, for example, was key for Dereum Labs in striking a deal with Airbus last year to explore how to tap Moon resources. “It’s important because of the difference in size between the two companies, one a global monster, and us a startup with a business model we’re still testing,” said Carlos Mariscal, Dereum’s CEO. That institutional support means the firm could access AEM’s installations to do research, for example, or piggyback on its partnerships with other space agencies.

The region’s space industry has some things going for it, including its location. The equator is prime real estate for launching. The Panama Canal is a handy way to transport bulky, sensitive hardware—that’s how the James Webb Space Telescope made its way from California to French Guiana for its Christmas Day launch. And costs in Latin America are also relatively lower than in places with a more established space sector.

As excited as they are, local space boosters are also realistic. Much of ALCE’s success depends on politicians’ willingness to keep the agency on the agenda, both locally and regionally. Brazil, one of Latin America’s heftier space players, passed on ALCE, for instance. It’s not hard to imagine the country joining the agency when Jair Bolsonaro ends his term—or other countries abandoning the venture after a new administration comes in.

ALCE will also need funding, a tough ask in a region where about a third of residents are poor. Judging by the budgets of some of the national agencies, space so far has not been a spending priority (Spanish.) Though entrepreneurs say the space industry will help solve problems on Earth, whether by creating jobs or enabling fixes like monitoring Amazon deforestation, they still have to make their case to the public.

There are potential risks to ALCE flopping, including an even worse case of brain drain. “If the region doesn’t make any concrete progress soon, it will lag further and further behind and lose human resources,” says Angel Arcia, a regional coordinator for the Space Generation Advisory Council, an international nonprofit that advocates for space professionals early in their career.

But the challenges ahead shouldn’t dissuade the launch of ALCE. If anything, the agency should set loftier goals to make sure Latin America doesn’t get left out of the next phase of space activity, says Dereum’s Mariscal.

“The future of humankind lies in expanding into space, and we want all of us to be able to contribute equally,” he said.

Your pal,

Ana

🌘 🌘 🌘

Imagery interlude

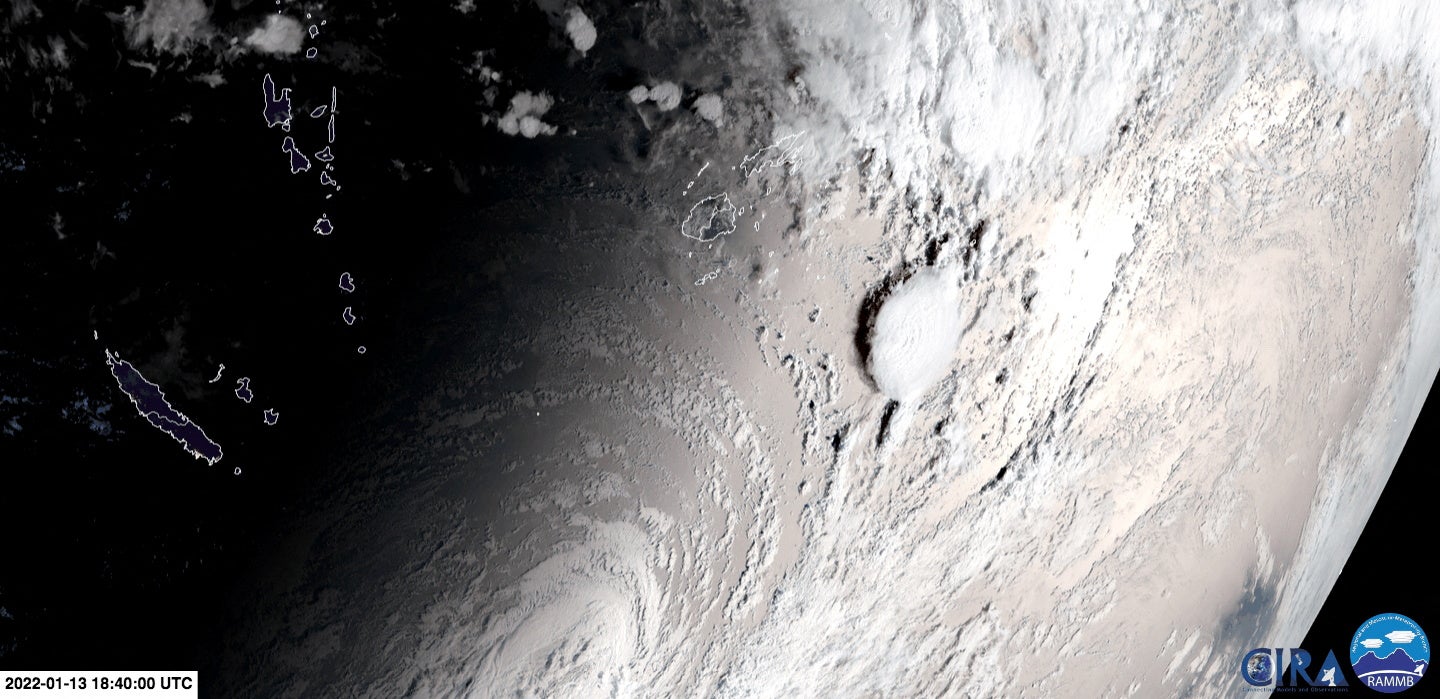

Plumes from Saturday’s eruption of an underwater volcano near Tonga were visible from space, here captured by a Japanese weather satellite. Aside from giving us a zoomed-out view of Hunga Tonga-Hunga-Haʻapai’s massive blast, satellite pictures also have been providing an early sense of the damage to surrounding islands.

🌍🌎🌏

Get obsessed. iPhone screens get their signature polish from rare earth elements. It’s one of the many slick tricks of rare earths, discussed on this episode of the Quartz Obsession podcast. 🎧 Listen to all this season’s episodes on Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google | Stitcher

🛰🛰🛰

Writer Tim Fernholz is on leave. He’ll be back in February.

This was issue 119 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send distinguished mice, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].