The world urgently needs a new way to track space junk

Dear readers,

Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere, this time hosted by Clarisa Diaz, a multimedia journalist on Quartz’s Things Team. Please forward widely, and let us know what you think. This week: junk map and ISS sunset ride.

🚀 🚀 🚀

Keeping track of space junk like SpaceX’s Moon-bound Falcon 9 is becoming an increasingly complicated task.

The amount of trash in space has shot up as we put more pieces of equipment in orbit, and so has the risk of collision. “A small object can have the effect of a hand grenade, just because of sheer velocity, and take out an entire satellite,” says Stijn Lemmens, a space debris expert at the European Space Agency.

Space debris not only threatens a growing array of key services on Earth—weather forecasting, GPS, the internet—but our overall access to space. Yet, our ability to monitor these stranded items is still imprecise at best.

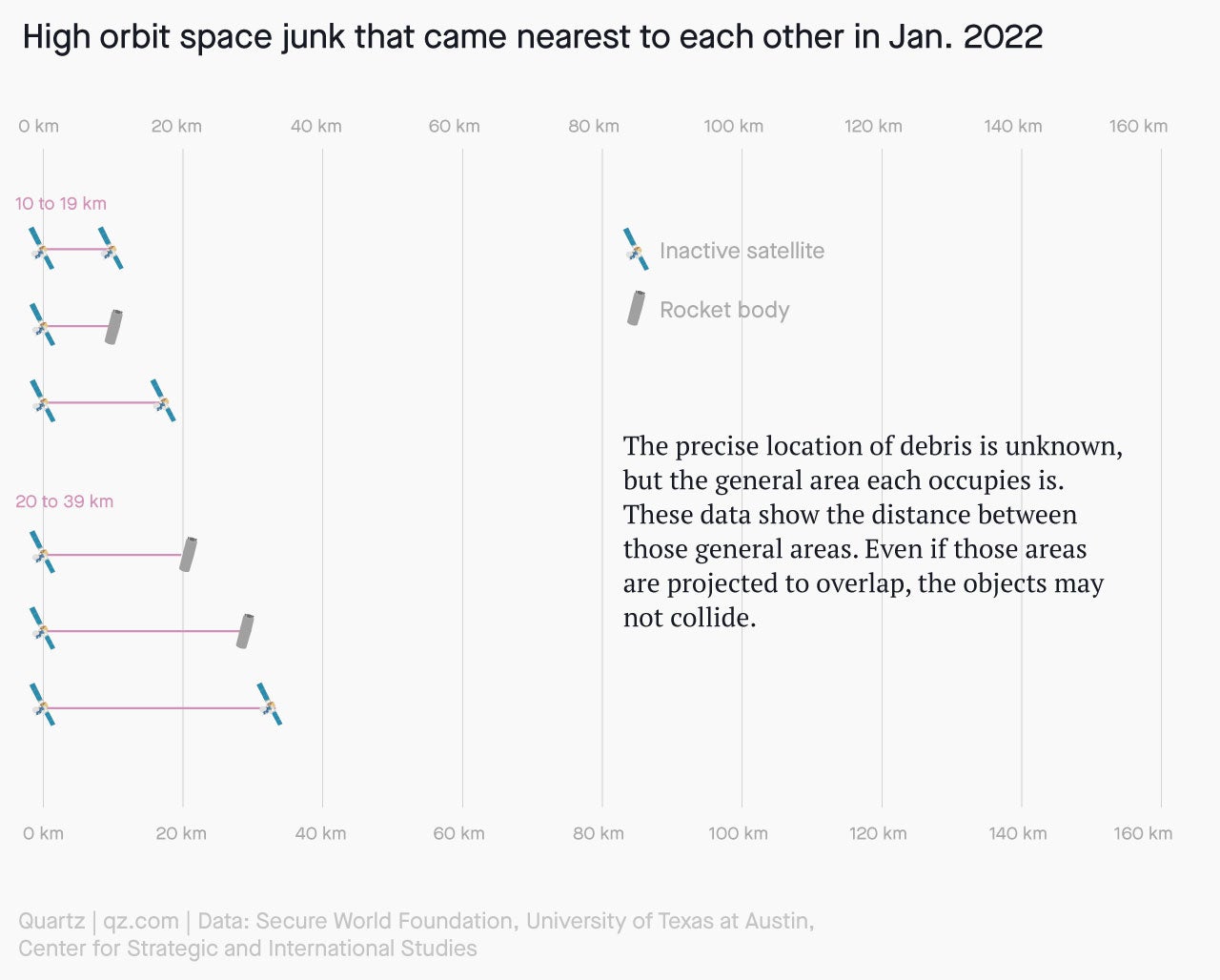

For example, we know that in January, there were at least 70 instances of objects in high orbit that came close to each other. How close? We can’t say exactly. For now, we can locate the neighborhood of a piece of junk, not its house number.

While culling this list out of tens of thousands of items is impressive, it’s just a snapshot in time. All these objects are moving, and their trajectories may change. Right now, monitoring systems can only get observations every few days. And there are limits to what they capture. Most of the radars currently tracking debris miss small pieces, and only go out as far as 4,000 km (the Falcon 9 piece, for example, is well beyond that).

The other big problem is that space monitors don’t fully share their data, so we don’t have a complete picture. Even piecing together what information is out there is hard because there is no common code. “We haven’t built a Rosetta Stone that tells me ‘When these people say Object 1, 2, 3, that’s actually Object 4, 5, 6,’” says Moriba Jah, a professor at the University of Texas in Austin and a professional space junk tracker.

Jah and others say more investment is urgently needed to create a global and more effective system to detect and identify objects. His goal: the equivalent of a Google Maps for space, which he is already working on as chief scientific advisor of Privateer, the space startup founded by Steve Wozniak.

Your pal,

Clarisa

(You can read a longer version of this essay here.)

🌘 🌘 🌘

Imagery interlude

NASA is getting ready for life after the International Space Station. In a report (pdf) to Congress this week, the agency detailed its goals for the storied space laboratory before it puts it out of commission by crashing it into the Pacific Ocean in 2031. Among them: Making it a stepping stone for humans to explore beyond low Earth orbit. Here is the ISS, looking in the other direction earlier this year. (See if you can spot Berlin, Copenhagen, and Oslo.)

🌍🌎🌏

Get obsessed. In a space-centric future, few things are more fun to think about than the dress code: From Space Force’s controversial uniforms to the limited sizing on pressure suits, the history of off-Earth fashion is chock full of wacky experimentation and ingenious invention. Back on this planet, another story of utility-meets-image can be found in the puffer coat. In the near-century since the first mainstream puffer was born of an ill-fated hunting trip, these sleeping bags with sleeves have become something of a status symbol. 🎧 To learn more, listen to this week’s episode of the Quartz Obsession podcast, the first of Season 2.

Listen on: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google | Stitcher

Sponsored by Alumni Ventures

🛰🛰🛰

Writer Tim Fernholz is on leave. He’ll be back next week.

This was issue 121 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send space junk street addresses, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].