The Race to Zero Emissions: The problem with buying an electric vehicle

In the last week, I’ve been trying to find my dad a new car, the electric Kia Niro. Amid the pandemic, EV sales are down 22% around the world, so new customers might seem a welcome prospect. I called four dealerships—and received four very different no’s.

In the last week, I’ve been trying to find my dad a new car, the electric Kia Niro. Amid the pandemic, EV sales are down 22% around the world, so new customers might seem a welcome prospect. I called four dealerships—and received four very different no’s.

The first Kia I called in Florida, not far from my hometown, told me the company’s factory in Korea was shut down indefinitely due to the coronavirus. He wasn’t expecting new EV inventory until 2021 (a Kia spokesperson contradicted this, saying all factories are now up and running).

The second enthusiastically set up a test drive the next day—but canceled when I later called to confirm. The third said the Niro EV wasn’t even sold in Florida. Would I like to check back in November?

A fourth dealer couldn’t wait to sell more Niro EVs after having just sold two. But they had sat on the lot too long, and he wasn’t keeping them on hand. I’m still waiting for him to call back with availability.

That, in a nutshell, is the dilemma facing many new EV buyers during the pandemic: too few models, too much confusion, and no certainty about what will come next.

The pandemic has only exacerbated a chronic problem for the industry. Automakers from Audi to Tesla face manufacturing delays, bottlenecks in battery production, and uneven sales given the US patchwork of state vehicle mandates. “You’re kind of always in a shortage,” said Ivan Drury of Edmunds, an automotive market intelligence firm.

The EV market won’t take off until buyers can reliably buy cars to match their preferences. It’s not about paint color: In a truck and SUV world, most EVs are still sedans.

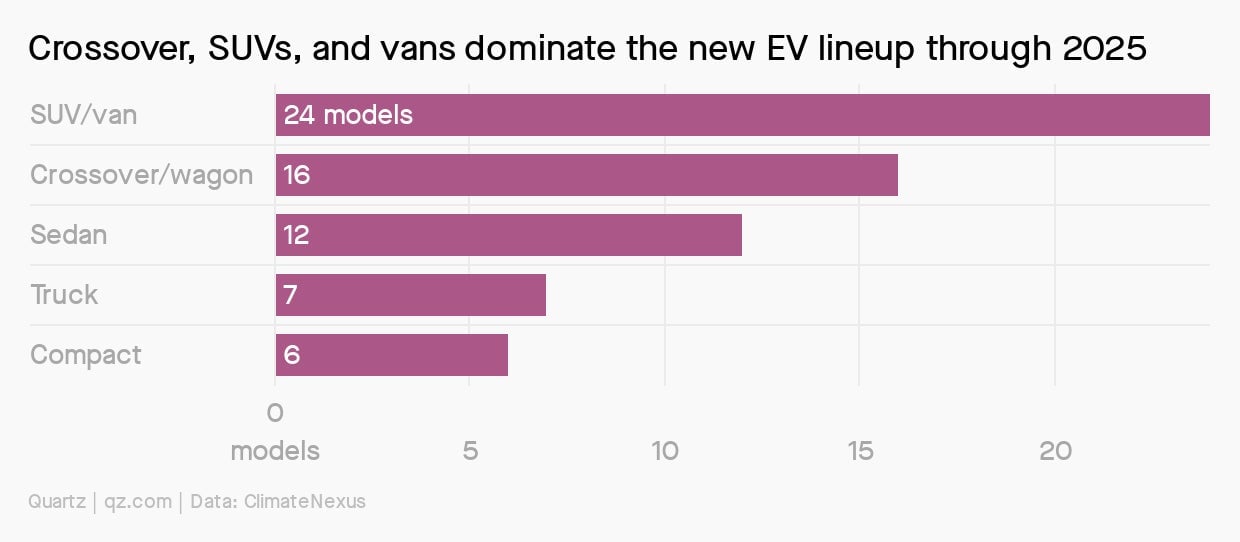

But that’s about to change. Next year will mark the arrival of more than 30 electric models, according to automakers’ announcements compiled by climate advocacy group ClimateNexus.

Even better for buyers: The new arrivals will hit the sweet spot in the auto market. At least 27 of the 30 new models arriving in 2021 will be trucks, SUVs, and “crossovers,” the svelte mix of a hatchback and utility vehicle.

Automakers, so far, are doubling down on their EV plans despite the pandemic. Electric vehicle sales have steadily risen, now accounting for 2.5% of global car sales, with China and Europe taking the lead. They’re counting on that trajectory to continue. “We haven’t seen anything that changes our view on EVs,” said General Motors’ Adam Kwiatkowski in May. “Full steam ahead.”

✦ You can read more about the banner year ahead for electric cars by signing up for a Quartz membership. ✦

Here’s what happened over the past week that helped or harmed the world’s chances of cutting greenhouse-gas emissions to zero:

Decreases emissions

1️⃣ A US federal court ruled that California can keep its emissions-trading market linked with Quebec’s. The combined markets, which first merged in 2014, form one of the world’s biggest cap-and-trade systems, raising at least $12.5 billion since 2013.

2️⃣ As the EU continues to debate its $850 billion economic recovery package, at least 1,000 clean energy projects—including a major new factory for electric vehicle batteries and industrial efficiency upgrades—are lined up to take advantage of the funds.

3️⃣ A group of the world’s largest oil and gas companies agreed to new emissions targets that aim to cut 36 to 52 million metric tons of CO2 per year by 2025. But the targets only cover the companies’ operational emissions—up to 90% of a company’s footprint is created when customers burn the fuel.

Net-zero (for now)

1️⃣ Chevron bought Houston-based Noble Energy for $5 billion, the first big fossil fuel consolidation of the Covid-19 era. The acquisition is part of the company’s plan to shift more of its portfolio from oil into natural gas, especially in Israel, where Noble has some choice fields.

2️⃣ Low oil prices are putting pressure on Middle Eastern and North African petro-states to speed up the diversification of their economies. That could be a problem for their non-oil-rich neighbors, which rely on remittances sent home by expat oil workers.

3️⃣ Morgan Stanley will become the first US bank to publicly track the emissions associated with its loans and investments. The bank has poured at least $92 billion into fossil fuels since 2016.

4️⃣ Burger King proposed a solution to curb methane from cow burps and farts: Let them eat lemongrass. Specially-made burgers will be available at a handful of restaurants in the US.

🔼 Increases emissions

1️⃣ In the UK, the coronavirus-related plunge in carbon emissions is quickly reversing as people return to driving and flying. Annual emissions are still expected to be about 10% lower than last year.

2️⃣ Canada systematically undercounts the emissions caused by logging in boreal forests, a report found. If deforestation continues at its current rate, the forest will capture at least 41 million fewer metric tons of CO2 than it would otherwise by 2030.

3️⃣ Seven countries, including the US, UK, and Japan, are contributing to a $15 billion package of loans for gas drilling in Mozambique. It’s the biggest such deal on record in Africa, in spite of the shaky economics of fossil fuel production on the continent.

Additional reporting by Tim McDonnell.

Stats to remember

As of July 19, the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was 413.87 ppm. A year ago, the level was 412.08 ppm.

Have a great week ahead. Please send feedback and tips to [email protected] and [email protected].