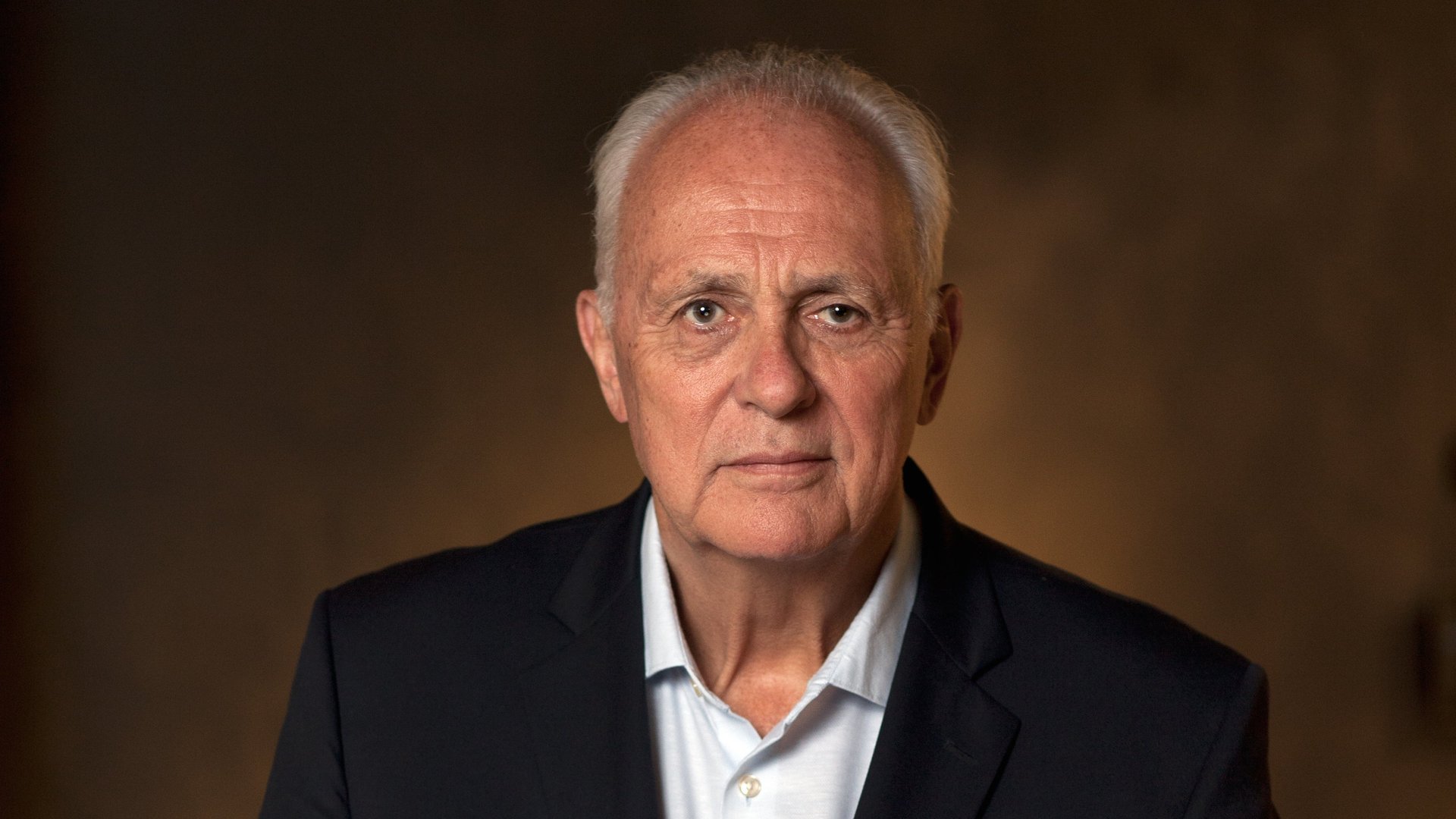

Former UN official Mark Malloch-Brown on Putin, Ukraine, and the case for multilateralism

The head of George Soros's Open Society Foundations says the UN is taking a "Cold War" approach.

Against all odds and widespread critiques, faith that multiple governments and institutions can work toward a shared goal abounds in New York, especially during the UN General Assembly. And you would be hard-pressed to find a more dedicated champion of multilateralism than Mark Malloch-Brown, a former UN deputy secretary general who has devoted more than four decades of his career to the cause.

A veteran of the World Bank, the UN Development Programme, and the UN Foundation, Malloch-Brown, who also served in the British government from 2007 to 2009 as the minister responsible for Africa and Asia, is today the president of George Soros’s Open Society Foundations.

Quartz caught up with him on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly to gauge his views on the UN itself, the war in Ukraine, the prospects for Russian president Vladimir Putin, the UNGA address by US president Joe Biden, and the case for continued belief in multilateralism. The following interview transcript has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

QZ: We last saw you in May, at the World Economic Forum in Davos, and you were deeply concerned about food insecurity, global inflation, vaccine inequity, and the war in Ukraine. Since Davos, has anything been if not solved by multilateralism then at least furthered along by it, on any of the big issues you’re concerned about?

MMB: Multilateralism has been bumping along with some pass grades—not many “A” grades. I think the UN secretary-general’s grain deal was very influential and having the IAEA inspectors on the [Ukraine] nuclear facility was also important.

What you’re seeing is a UN which has been more engaged and animated than the sort of shock with which it greeted the conflict initially. And the Bretton Woods institutions have been moving on the equally important economic side.

So I think they’ve been good on consequences [but] completely absent on causes. They just can’t get at those causes because they don’t have the consent in the Security Council to do so. But one little silver lining was Biden’s conversion on UN Security Council reform. The US, which has always been the most immovable on this, suddenly is seeing virtue in reform.

And that’s because of Ukraine?

It has really stirred the embers of Security Council reform, [after] people talking about it for years and nothing happening. Now suddenly the embers are showing a little red heat again. I’m not sure they’re going to catch fire and the world is going to change, but at the margins, this is good.

But it still seems to be shaping up as a Cold War UN, where it’s active on humanitarian [issues], active on technical tasks like inspections of nuclear weapons or facilities, but not in the political inner kitchens because there isn’t the consensus amongst major powers to allow it to act there.

So do you still have faith in multilateralism?

I do, because however imperfect the results, it remains the only serious way to address issues which simply just don’t lend themselves to national solutions.

In a way the case for multilateralism looks stronger than ever, partly because of the pigheadedness and head-in-sand approach of so many national governments. But of course, it is that approach of national governments which has led to the crisis of multilateralism. I mean, multilateralism is not an alternative to bad national governments. It is intergovernmental. It requires governments to share values and approaches, and in the case you find common ground between each other, coming together to drive shared solutions.

What issues are best solved by multilateralism?

One of the things I went to this week was the Pacific Islands meeting, around the devastating impact of these islands that are sinking. They have impeccable climate credentials that are living completely within the Paris boundaries. But it doesn’t make a toss of difference because it’s our emissions which are driving [climate change].

It’s incredibly difficult to wake the world up and into consciousness about what its activities are doing to these people on islands literally on the other side of the world. But of course, it starts with those islands and then it comes roaring back to places like New York, where I’m sure you know of people whose apartments have flooded and so forth.

With the joined-upness of this, the way the damage is spreading, one country’s salvation doesn’t live within its own boundaries. Even if the US did everything John Kerry wanted domestically, there’s still going to be a threat to New York or coastal Florida unless there’s action across the world. And climate is not exceptional in that way.

Whether it’s addressing migration flows or the state of global economy, these things no longer lend themselves to strictly national solutions.

How do you think Russian president Vladimir Putin is faring right now?

You know, coming into this General Assembly, it sort of looked as though Putin had things going a bit his way. And in fact, if you look at the speeches by many heads of government, they have appeared to have quite carefully avoided taking sides in their GA speeches. But my God, Putin has committed some massive own goals in the last few days, first appearing to have lost the uncritical support of China and the neutral support of India, with both leaders, Xi and Modi, expressing clear reservations last week at the Shanghai Cooperation summit.

And now, having been given a really bloody nose by the Ukrainians, he gives this dark speech on the eve of Biden speaking at the General Assembly. If you’re Biden, you couldn’t hope for better. He makes Biden look like a statesman and friend to the world after these threats to go nuclear, and apparently the flights out [of Russia] are really busy, full of able-bodied young men. There was always a risk that if Putin did this, he would start to spark real internal divisions.

I was planning to ask if you were more concerned now about the Ukraine situation since Putin’s speech, but it almost sounds like you’re more optimistic.

No, I’m not—I’m not optimistic. I think it’s become highly unpredictable and dangerous now. I think it’s a real risk of something very bad happening.

I still think it’s very unlikely he will really go nuclear. Russia’s own protocols for nuclear use don’t seem to be met. And it’s not clear how his own military commanders would respond to such an order. They’ve spent much more of their military careers thinking about nuclear deterrence strategies than their western counterparts, frankly because they’ve always known they’ve had a weak traditional military. So there’s a lot of theory and theology around when to use nuclear weapons and when not. I think it’s still very unlikely they will.

But if they did, there almost certainly would be a US response. So we’re in very tricky, dangerous territory. This is the classic thing of the bad guy cornered.

How else are you thinking about the Ukraine situation based on what you’ve heard this week?

On the military side, probably a narrow advantage now rests with the Ukrainians. With the American army training of them, also by the Brits and others, it really seems to have given them a temporary edge.

Meanwhile, the Putin mobilization of troops is not something that’s going to help the Russian side for quite a while. And they seem to have resupply problems. So I think on the military side, while it’s not going to allow Ukraine to decisively break through, they’ll continue to push back. But that gets you to a stalemate, not a victory.

The other bit, and it’ll be more of a conversation as we move to the annual meeting of the World Bank and IMF in October, is that Ukraine is running a $5 billion a month deficit. That’s a big number. And so, it’s really that the West mustn’t let the economic support for the country run out. You know, everybody’s focused on the battlefield. But this really could be “the economy, stupid.”

Last question: What are you seeing or feeling at UNGA in terms of America’s role in the world, with Donald Trump now long gone from office and UNGA back in person on US soil?

I think this it’s too soon to know, but my guess is the speech [at UNGA] will have done a lot to consolidate Biden’s position as leader of the free world. But I don’t think it will have laid to rest the West’s anxieties about a Trump comeback.