The trick to sticking to a project every day—for years

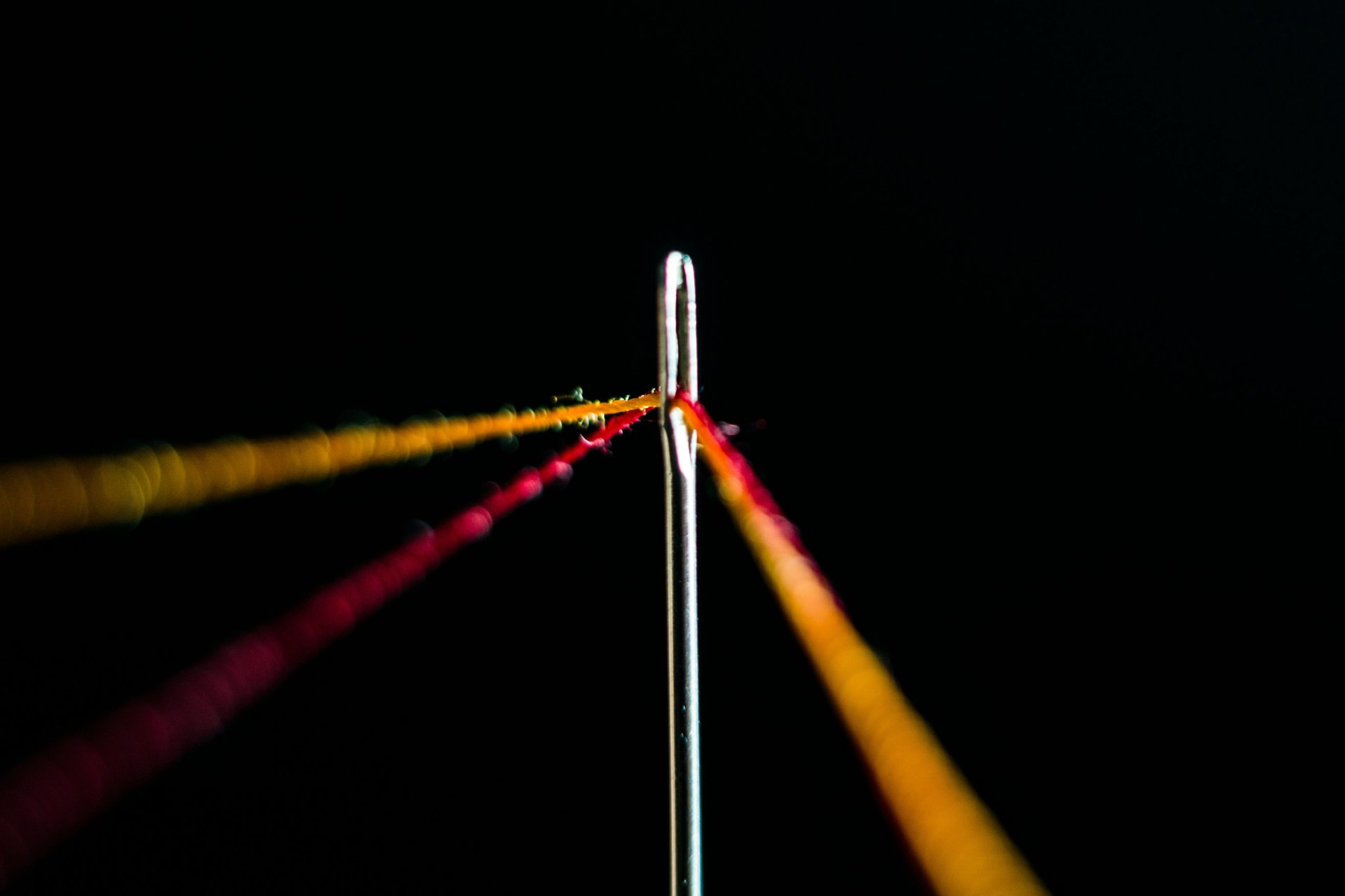

To stay committed to a project, keep following the thread.

It’s your first day at a new job. You’ve already chatted twice with IT, forgotten the name of the third coworker on your left, and debated the appropriateness of dipping out for an afternoon coffee. Then a little voice whispers: You will stay in this job for six years, three months, and two days.

Excuse me? Six years (and three months and two days) is a good chunk of time when measuring a career—maybe an overwhelming amount of time. Yet plenty of us will probably hit that marker at a company or career patch, even if we rarely think or project that far ahead. Instead, we show up, befriend colleagues, learn new skills and workplace dynamics, and keep going.

It’s funny how we don’t give our own creative or personal projects the same level of consistent attention. That networking group you want to put together gets half-hearted focus once every six months. That vintage resale shop you want to get off the ground remains a dream. That daily journaling habit and crystalline morning routine you want to keep lasts three, maybe four, days before life gets in the way.

Why can’t we commit to our own projects for the long-term? A few obvious reasons. We might not be getting paid from them (yet). A trajectory might be elusive. We might require more feedback, structure, or boundaries.

There’s another reason that’s hard to admit. You might be hoarding your ideas. You’re keeping them pristine for tomorrow or next month or next year. Acting only when it feels “right” can turn a great idea into a persistent fantasy. If an employee only worked on days that feel “right,” they’d rarely show up. At a job, there are always good, bad, and mediocre days. But one thing’s consistent: there are a lot of days, which translates to a lot of opportunities. If you want to commit to—and pull off—a project for yourself, start treating it like you do much of your other work: simply begin adding up the days.

The seven-year project

As of today, I’ve sent 1,155 newsletters to subscribers of Brass Ring Daily, my newsletter featuring short notes of encouragement every weekday. If someone told me seven years ago that I would write over 1,000 emails on work, life, and creativity, I’d reply: Not a chance. I don’t have enough to say. I’ll get tired or bored or both.

Yet here they are: 481,299 words. Proof that small progress adds up to a grand total. The most important lesson this seven-year practice has taught me: It’s impossible to run out of ideas.

People often ask me, “How do you find something to write every day?” The answer, I’ve learned, is that I find something because I’m looking every day. If I wrote a weekly or monthly newsletter, I’d look for ideas once a week or once a month. We find what we seek.

Hold on to the thread

The novelist Eudora Welty’s ideal writing day, detailed in Daily Rituals: Women at Work by Mason Currey, involved waking early followed by a long stretch of work without interruptions or obligations. But the real key to her writing “was to know that the following day would be exactly the same,” writes Currey, adding up to part of “one long sustained effort.”

“It’s the act of being totally absorbed, I think, which seems to give you direction,” Welty said. “The work teaches you about the work ahead, and that teaches you what’s ahead, and so on. That’s the reason you don’t want to drop the thread of it. It is a lovely way to be.”

We often assume our creativity and effort exist within fixed boundaries—that we’ll only ever have a certain number of ideas, or reach some kind of dead end. Instead, why not acknowledge there’s much we don’t know about our future selves? One good idea, when actually executed, can lead to a dozen new ideas. What if there’s a thread to follow, and the more we continue, the farther we’re led by the thread?

Beware the hoarding mentality

The secret to maintaining a long-term project is having faith that whatever you share or create today will naturally lead to tomorrow’s work. You will always find something new. Each day is the opportunity to unspool a little bit more and walk forward.

Say, for instance, you always dreamed of writing a book. You have a brilliant idea that will storm the bestseller lists. The idea is so good that you fear it will get stolen (ignoring, of course, the fact that executing an idea is much more difficult than coming up with an idea, and these potential thieves are probably tired from trying to dream their own ideas into being, so they’re probably not inclined to steal yours). The idea is so good that you want to hold on to it for some future use. When you have the right connections. When you have the right slab of time. When someone arrives with a blank check. And you hold it close and do nothing. You hoard your idea for an imagined future.

Making your own way forward

In 1965, the artist Sol Lewitt wrote a letter to young sculptor Eva Hesse that sings as an anthem for “doing.” (Benedict Cumberbatch once performed the letter; it’s six minutes worth watching.) To encourage the artist, Sol urges her, “Try and tickle something inside you, your ‘weird humor.’ You belong in the most secret part of you. Don’t worry about cool, make your own uncool. Make your own, your own world.”

There is magic in creating your own world away from what is cool or right. Consider other possibilities: Take two hours and outline the messiest version of your script. Pitch your boss on a wild video series. Gather three friends, tell them your idea, and ask, “What moves you?” Type for 15 minutes every day for one month to make chapter one real.

Progress creates progress. Today’s tiny effort captures ideas, connections, people, facts, and inspiration to add to your web. Projects need to breathe outside of your desktop or Moleskine notebook. To work long-term on anything, first get something out today and watch your well of possibilities refill by tomorrow.

Forget the feedback (for now)

Numbers, statistics, and metrics will fail you. When we tie our progress to something outside our control, our highs and lows are yoked to them as well. Say you’ve always wanted to start a podcast. Instead of obsessing over listener numbers, what if you became intent on providing more value in each episode? Publish more often — and create an even more compelling product — and you’re designing more opportunities for people to find you. But do not tell yourself, I need people to listen. Rather, reframe your mindset to: I am sharing something important.

You don’t want to burn bright and burn out. You want a sustainable, long-term commitment. You want to see your project come to life.

So what now? Stop hoarding. Get out your idea as quickly as you can. Make something new—something you like. Show up more often, commit to quality, and never fear running out of ideas. You won’t. And in six years (and three months and two days), you’ll look back on this moment and be glad you took the leap — not to please anyone else, but for yourself.