China’s robot Olympics just ended. Will humanoids be in our homes in the next year?

The World Humanoid Robot Games turned pratfalls into policy theater — showcasing just how far robots still have to go

Lintao Zhang/Getty Images

At Beijing’s National Speed Skating Oval — the same arena where Olympians in 2022 carved across the ice — the opening ceremony looked familiar enough: lights, flags, fanfare, and athletes lined up for a global contest. But instead of figure skaters or hockey players, the stars were steel-jointed humanoid robots.

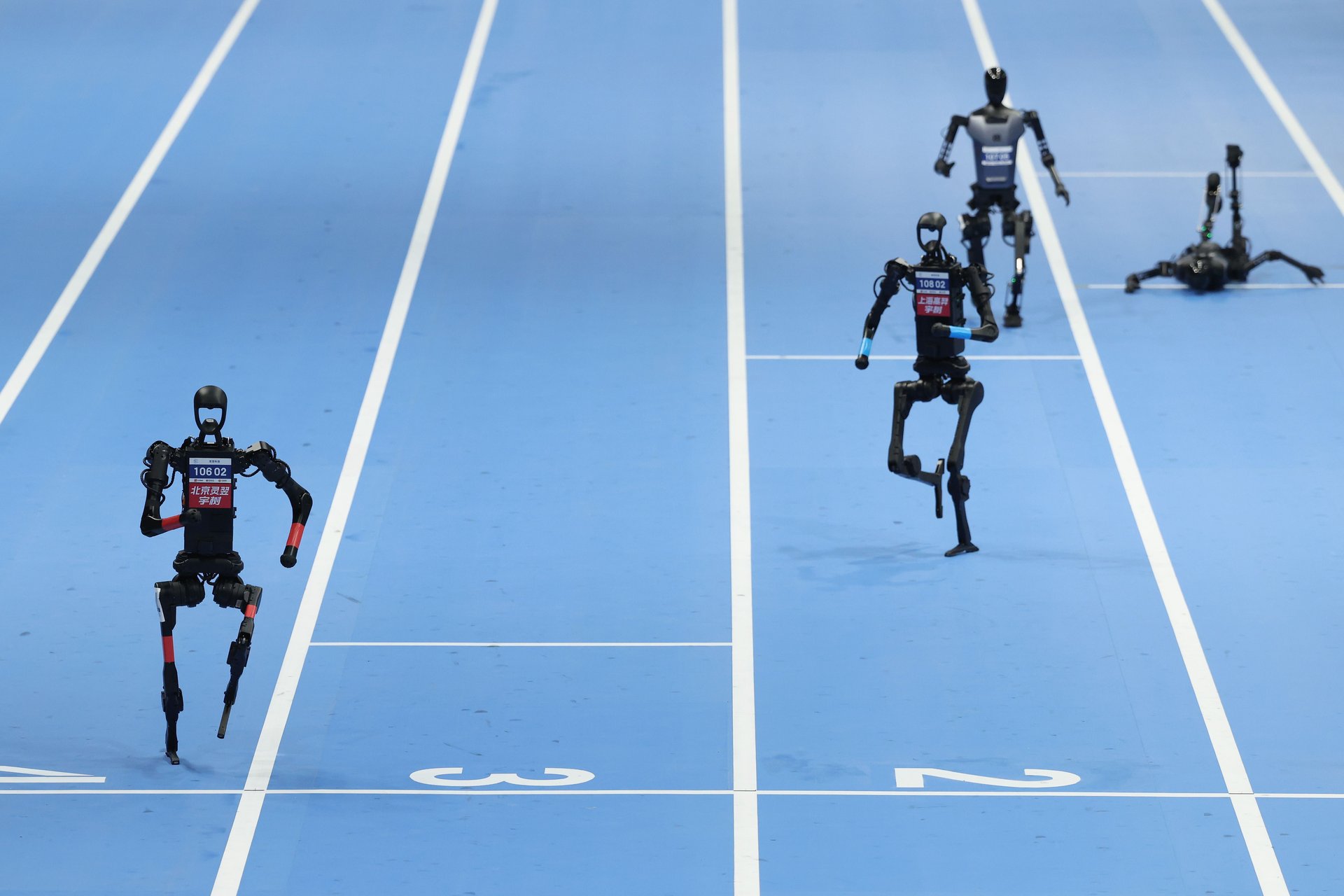

They danced hip-hop, performed martial arts, strummed guitars, and even modeled outfits alongside human performers. One collapsed so hard during the introductions that staffers had to carry it off the floor like an injured player. The crowd roared anyway. When the competition itself kicked off later in the week, the pratfalls only multiplied. In the sprint races, some robots managed a few steady strides, while others face-planted straight out of the gate, crumpling into heaps of wires and limbs. A few froze entirely, forcing handlers to jog in and reset them. The stumbles, crashes, and stiff-limbed runs turned the races into slapstick theater as much as sport — and the audience loved it.

The world’s first “robot Olympics,” officially called the World Humanoid Robot Games, gathered more than 500 robots from 16 countries and staged them across 26 events — track races, soccer matches, boxing bouts, and even chores such as cleaning hotel rooms. The stated goal was to test the limits of embodied AI, but the real result was a reminder of just how far those limits still stretch. Humanoid robots could run — sort of — but slowly and stiffly, and they needed frequent rescues from human handlers. The robots could box, but the matches looked more like clunky hugs than prizefights. They could play soccer, but only if you were willing to redefine “playing” as “falling near the ball until someone managed to kick it” — a tangled crash involving multiple “players” resulted in metal limbs sprawled all across the field

Yet for every spill, there was a glimpse of progress: a robot that got back on its feet without human help, a team that strung together passes in humanoid soccer, a cleaning bot that finished its chore in under 10 minutes. The wipeouts became part of the spectacle, an inkling of proof that embodied AI is crawling, wobbling, and sometimes running its way into viability.

Companies from Tesla to Amazon are pouring billions into humanoid robot research on the promise that one day these bots will fold laundry, bring in the groceries, or keep watch while you’re away. But the Beijing showcase made clear that the reality is more halting. Sprinting across a track or cleaning a hotel room isn’t the same as reliably unloading a dishwasher or scrubbing a counter — it’s harder to account for the chaos of pets and kids and more — and for now, most robots still need human spotters nearby. But the fact that they can do pieces of these tasks at all, however clumsily, is why investors and tech giants keep betting that today’s tumbles could, eventually, translate into tomorrow’s — or next year’s, or next decade’s — domestic help.

From pratfalls to policy

Beijing didn’t stage the Games as comic relief. This was industrial policy with spotlights, a showcase for China’s ambitions in humanoid robotics. The government has already poured tens of billions into subsidies and is planning a trillion-yuan ($137 billion) fund for AI and robotics startups to underline its ambitions. Humanoid robots, Beijing insists, aren’t a novelty — they’re the future of work, healthcare, and maybe even daily life. The robot Olympics weren’t just about public laughs — they were about collecting edge-case training data from robots stumbling in unpredictable scenarios. Every fall becomes a labeled data point, every collision a lesson in physics. In embodied AI, mistakes are fuel.

The medal count reinforced Beijing’s dominance. Chinese firm Unitree Robotics dominated the track events, winning gold in the 400- and 1,500-meter races — even if the winning time for the longer race was 6:34, nearly double the (human) men’s record. Another Chinese player, UniX AI, earned gold in a cleaning contest by tidying a staged hotel room in under nine minutes. That was impressive in context — it beat other competitors handily — but it still underscored the gap between a one-off competition and real-world reliability. In between those flashes of progress were endless slip-ups: robots tumbling over hurdles, colliding in soccer scrums, or freezing mid-task until technicians intervened.

The U.S. isn’t sitting out, but its approach is different: Silicon Valley promises, not state subsidies. Elon Musk has declared that Tesla’s humanoid robot, Optimus, will be in limited production by 2025 and may one day eclipse the company’s car business in importance. Demo videos have shown Optimus folding T-shirts, watering plants, and frying an egg. Critics note that many of these demos look heavily choreographed, if not remotely operated. But Musk continues to insist that Optimus will soon populate Tesla factories before eventually landing in homes.

Amazon is playing the pragmatist. It has spent years testing Agility Robotics’ Digit in warehouses, where the bipedal has carried bins, stacked totes, and unloaded delivery vans. In test facilities in San Francisco and at select fulfillment centers, Digit waddles around obstacle courses, carefully lifting and placing objects. The promise is clear: a humanoid robot helper that can slot into the spaces designed for humans, without expensive retrofitting. But the execution is fenced in. Digit can handle controlled tasks, but not chaos — the very thing that warehouses are full of. That hasn’t stopped Amazon from talking about humanoid robots as if they’re inevitable, a “when, not if” scenario.

Then, there are the startups. California-based Figure AI has raised billions from Microsoft, Nvidia, and OpenAI on the back of glossy renderings and confident timelines, pitching a general-purpose humanoid that can work in warehouses today and homes tomorrow. Other U.S.-based companies, from Boston Dynamics to 1X Technologies, offer variations on the same promise: The humanoid robot revolution is imminent.

The hype gets more surreal in the home. At the robot Olympics, China showed off bots that could cook and clean. In the U.S., Weave Robotics is trying to convince early adopters to put down more than $10,000 for Isaac, a humanoid robot designed to fold laundry and pick up toys.

On YouTube, Isaac looks magical. The torso telescopes up and down, the arms reach out delicately, the hands stack folded T-shirts with care. In person, it’s slower — methodical in a way that feels less like magic and more like waiting for paint to dry. The company pitches Isaac as “your eyes and ears” at home, capable of watering plants, feeding pets, and tidying the living room. But when Isaac stalls — and it does — a remote human takes over via teleoperation. Weave calls this “hybrid autonomy.” The marketing spin is that every teleoperated recovery becomes training data, making the robot smarter. The blunt reality might be that you’ve just paid five figures for a machine that occasionally calls tech support to finish folding your socks. And in the real world, a real-life housekeeper is cheaper and more reliable.

Self-driving déjà vu

If the stumble-filled games felt familiar, it’s because we’ve seen this movie before. In 2004, DARPA staged its first driverless car “Grand Challenge” in the Mojave Desert. Fifteen teams showed up with clunky, experimental vehicles meant to navigate a 142-mile course. None got close. The farthest went just seven miles before veering off the road and catching fire. The event was branded a flop at the time — but in hindsight, it was the start of a multibillion-dollar race.

DARPA ran another challenge two years later, and this time, several vehicles finished. By the early 2010s, Google had fleets of self-driving Priuses roaming California streets, and every major automaker was funneling money into the field. Investors and policymakers hailed a driverless future as inevitable: If the cars could drive themselves in a desert, surely they’d soon be chauffeuring commuters down Main Street.

But fast-forward to today, and driverless cars are still a half-step promise. They exist, but mostly in constrained pilot zones or as glorified shuttles, not as ubiquitous replacements for human drivers. Cruise and Waymo are burning billions to keep their robotaxi fleets alive. Automakers such as Ford and VW have dialed back once-grand driverless ambitions. A full self-driving car that you can buy at the dealership remains as elusive as it was two decades ago. The gap between a headline-grabbing demo and a reliable, scaled product turned out to be not years but decades — and still counting. The lesson isn’t just that breakthrough demos matter; it’s that timelines stretch, obstacles multiply, and hype usually gets ahead of reality.

Musk’s Optimus promises echo the bravado he once applied to Tesla’s self-driving software — which still requires drivers to keep their hands on the wheel. Amazon, too, has pitched robotics as the next frontier, but its flagship Astro home robot has been quietly scaled back from the ambitious vision it debuted in 2021. Both companies are leaning on the same playbook: big promises, slick demos, and timelines that don’t necessarily survive contact with reality.

The humanoid games echo the auto industry’s same awkward first act. Robots collapsing in sprints and clinging to soccer balls are today’s equivalent of cars stuck in sand traps. The spectacle isn’t about performance now so much as seeding an ecosystem: investors with billions to spend, engineers looking for the next career-defining problem, and governments eager to claim leadership in a field with military, economic, and social stakes. The Beijing competition could be remembered as the awkward first steps of an industry that eventually finds its footing, the way DARPA’s desert wipeouts seeded today’s still-maturing driverless sector. Or, humanoid robots could follow the same tortured arc: Perpetually “just a few years away,” consuming billions while physics, liability, and public trust keep the finish line out of reach. Investors betting that robots will be scrubbing countertops and unloading dishwashers in the near future might want to revisit the road not yet traveled in autonomous cars.

The messy middle

The pitch for home robots leans heavily on convenience. They’ll scrub your dirty pots and pans after a dinner party, mow the lawn, scoop out the litter box, walk the dog, and organize your closet. They’ll be your eyes and ears. But an always-on robot is also a camera with legs, mapping your floor plan, logging your routines, and recording every object it touches. The “eyes and ears” promise could double as a privacy nightmare.

Liability is another issue. What happens when a household bot crushes a pet’s tail? When a robot slips on the wet floor and smashes a coffee table? The insurance industry hasn’t begun to catch up. Then, there’s labor. Advocates frame humanoid robots as replacements for “mundane” work. At the moment, the hybrid autonomy model means jobs aren’t eliminated; they’re moved. Someone, somewhere, is still picking up Legos — just through a joystick and a video feed. For now, at least, the disruption looks less like replacement and more like rerouting.

The robot Olympics made clear that even the best robots remain fragile, slow, and expensive. Optimus may roll off a line in 2025, but Musk himself admits it will start in factories. Amazon’s Digit is still kept contained in trials. Isaac can fold shirts, but not without patience — and sometimes divine intervention. But what the games did prove is that humanoid robots are crossing a threshold. They’re moving from glossy, controlled demos into messy public tests. Every tumble on the Olympic track is being labeled as a training dataset. Every viral clip of a face-plant is another reminder that embodied AI is progressing, haltingly, in plain view.

The stakes are enormous. If humanoid robots can deliver on even a fraction of their promises, they could reshape labor markets, supply chains, and daily life. If they can’t, the industry risks becoming another overhyped money pit. For now, the robots wobble between the two. Investors keep writing checks. Governments keep staging spectacles. Consumers keep laughing. The crowd in Beijing seemed to understand the absurdity. They weren’t watching the future roll gracefully into the present; they were watching machines struggle through adolescence. They clapped anyway, as if to will the robots to keep trying. Perhaps that’s the most honest picture of humanoid robotics today: funny, flawed, and still far from home — but backed by too much money, and too much ambition, to stop stumbling forward.

So will humanoid robots be in your home tomorrow? No. Next year? No. The next decade? That’s the trillion-dollar question.