The great American road trip in the eyes of south Asian immigrants

On this summer day in 1995, sixteen-year-old Odessa Despot had made the questionable decision to wear baggy jeans, a Columbia jacket, and Timberland boots—the unofficial uniform for a teenager from Queens, New York. So the first thing she remembers about her family’s visit to Plimoth Plantation in Massachusetts is the unbearable heat.

On this summer day in 1995, sixteen-year-old Odessa Despot had made the questionable decision to wear baggy jeans, a Columbia jacket, and Timberland boots—the unofficial uniform for a teenager from Queens, New York. So the first thing she remembers about her family’s visit to Plimoth Plantation in Massachusetts is the unbearable heat.

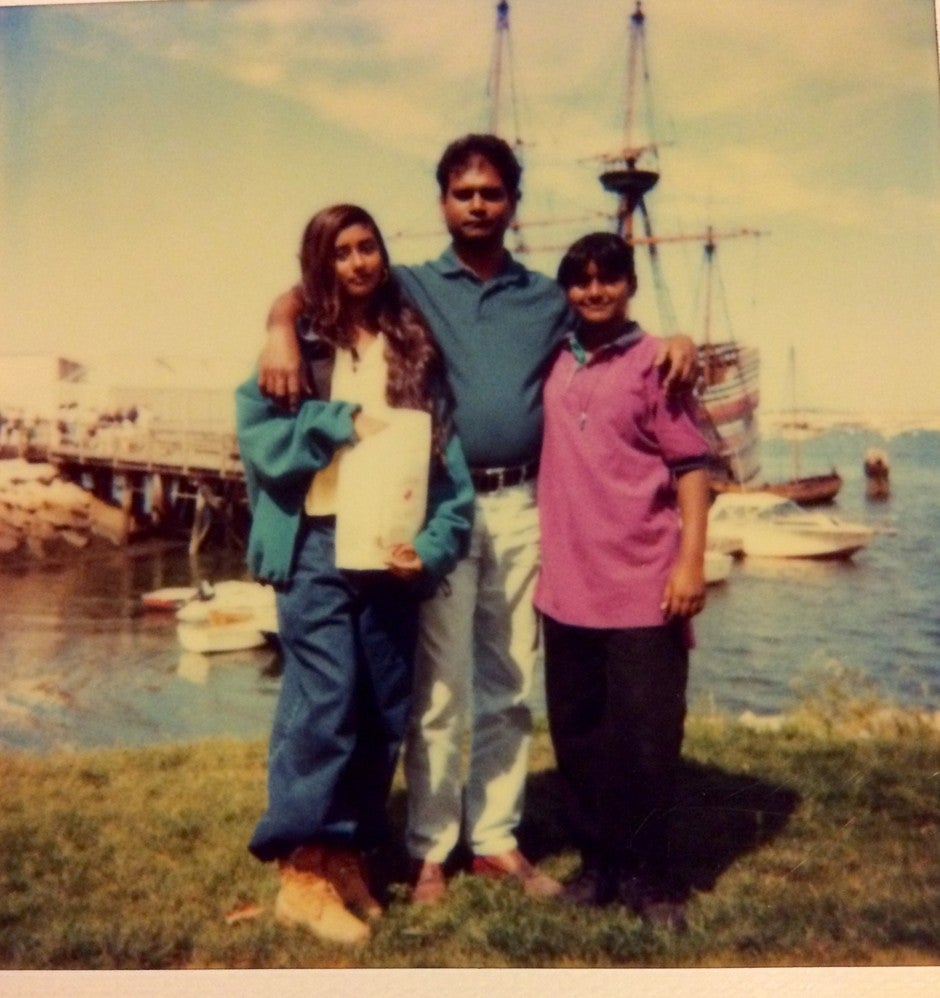

Tourists walked in and out of stores on the lively streets, perusing souvenirs and sampling salt water taffy. Despot tasted some herself, and decided she wasn’t a fan. But the lobster rolls in Plymouth—those definitely lived up to the hype. At some point, she, her sister, and their dad clicked a photo in front of the full-sized replica of the Mayflower, the ship on which the Pilgrims had arrived in the 1600s.

Thinking back, she wonders if her family truly understood the significance of this trip. Her parents, who were undocumented at the time, likely didn’t. “The idea of white people coming on a ship and moving to the US was not something that they connected with, I don’t think,” she says. “In their minds, white people had always been in America. To be American was to be white.”

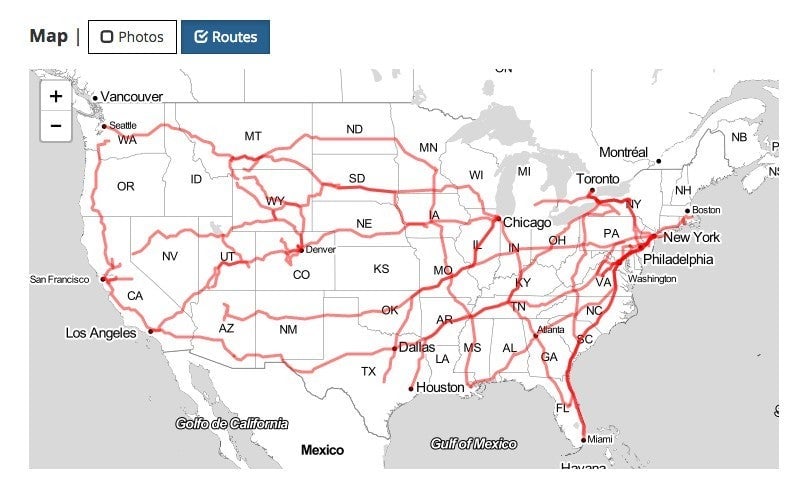

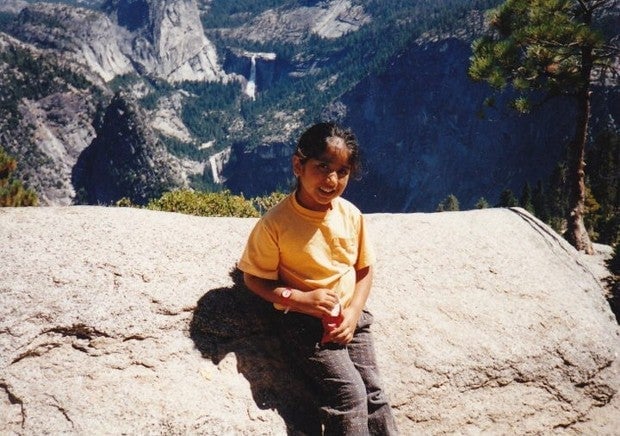

This photo of Despot and her family now lives online, as a part of the Road Trips project from the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA). The archive, which celebrates its ninth anniversary this week, recently put out a call asking south Asians to contribute photos of their travels in America, along with route information and anecdotes. So far, they have around 50 submissions showcasing experiences across nationalities, religions, age, sexual orientation, and legal status.

Being on the open road is a quintessentially American rite of passage—it’s a way of seeing America and being seen by it. To get behind the wheel and drive, in this country, is to claim ownership over the landscape and over one’s own identity. Or, at least that’s the way it’s often portrayed in books and movies.

In reality, the right to travel freely and safely has been withheld from certain groups. Throughout history, vast swaths of land were deemed off-limits for people of color, either through policy or practice. During Jim Crow segregation, black travelers consulted the Green Book, a travel guide that showed routes they could take to avoid violence. And while things have certainly changed, driving in a car can still be a death sentence for a black person, even in their own hometown.

Immigrants, too, have experienced a limited America. Whether they’re in the country legally or not, the cost of driving can be prohibitively high. And being welcomed in all parts of the country isn’t a guarantee. Violence against south Asians goes back to the 1900s. And even in 2017, immigrants are shot at in bars or in their own driveways because someone decided they do not belong.

The goal of SAADA’s project is to push back against that backdrop of xenophobia and to reimagine a fundamentally American experience from the perspective of immigrants who’ve dared to wander. It’s “trying to recognize that to travel as an immigrant of color or south Asian is an act of bravery,” says Samip Mallick, the co-founder and executive director of SAADA, “and trying to assert by traveling across the country that this country is ours as much as it anyone else’s.”

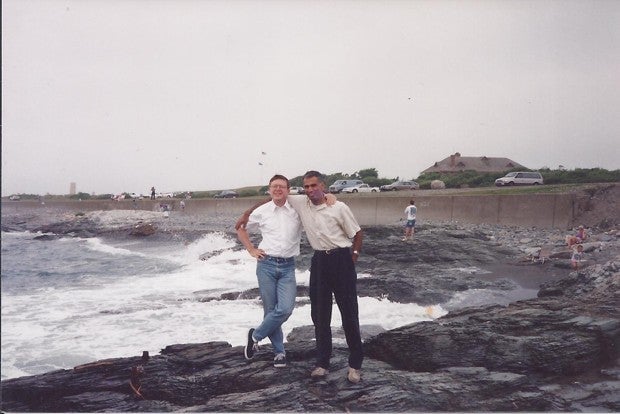

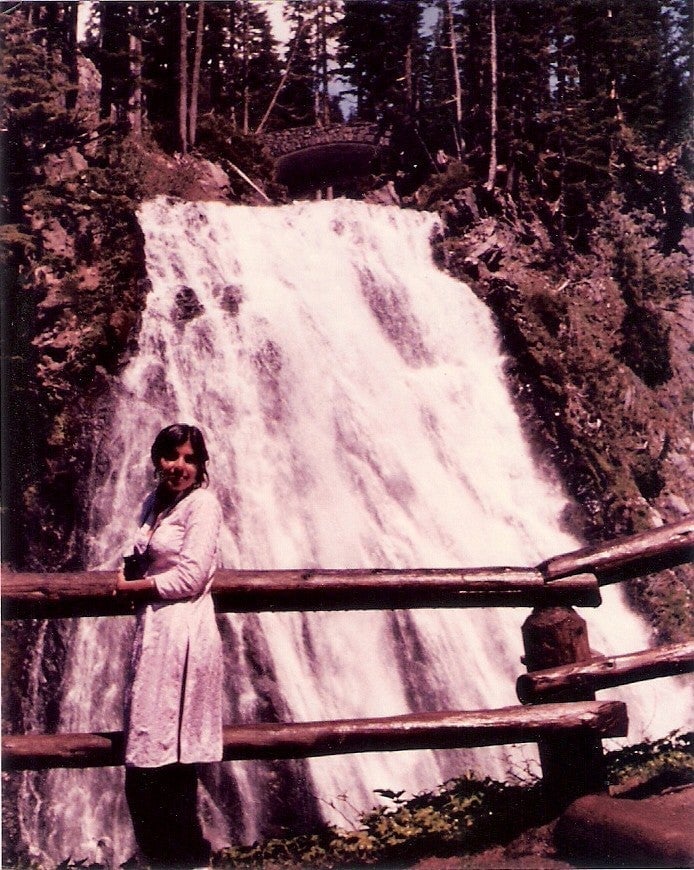

South Asian families have put their own twists on the American road trips. Many of the accounts submitted to SAADA fondly mention the Indian snacks—the idlis, the puri-aaloo, the hari chutney sandwiches, and the masala potatoes roasted over the bonfire in place of s’mores. Some people recount queuing up songs in native languages and setting off on the road in their American-made cars, with extended family in tow. Others talk about first snows, the night-time lights over Niagara Falls, and the largeness of the Grand Canyon.

They also describe the difficulties. In her anecdote, Veena Mandrekar remembers how her parents were refused service in one motel after another in a small town they were driving through. “This is the only time we felt as outsiders,” she writes in her testimony. “At some level it is funny, but it was not so funny at the time.” In another, Omar Tiwana writes that he was anxious about moving to Texas after retirement, for fear of racism. “I kept reassuring myself that this was ‘America’, with constitutional freedom for all—including Asian Americans—citizens to travel and relocate in any state of the Union,” he writes. “To be safe, I decided to check up a bit.”

When Odessa Despot looks at the photo she submitted, she is reminded of the larger journey it represents: the path to becoming American.

Her parents had underestimated how tough, time consuming, and expensive it would be to get citizenship. Most people do. While the process unfolded, her father, in particular, struggled. He had trouble holding down jobs and coped by drinking. Like many people, he had fixated on the promise of American life—or the version of it he saw on shows like “Married…With Children.” And the reality just didn’t match up. “He wasn’t as critical of it as he should have been, until he got here, and realized, ‘Oh, wait, I’m not going to be treated fairly here,’” Despot says. But he held on to the idea of America. He insisted that the kids lose their Trinidadian accents, that they listen to “cowboy music,” and that they take a road trip in their newly acquired, very American silver Dodge. “When I look at that photo, I think, ‘holy moly, my family is so resilient to stay intact amidst all of the various environmental stressors,’” Despot says.

Now, by some measures, Despot is American. She has the passport to show it. She’s got a college degree and works as a clinical psychologist in upstate New York. But whether she feels American depends on the definition of “American” and who’s deploying it. This photo reminds her that she’s entitled to her own definition. “My family and I have created a life here and built family, career, community, and memory,” she says. “So America also belongs to us and we belong to it, despite the myth of a singular ‘American.’”

This post first appeared in CityLab.