The objects Hindus and Muslims carried across the border during Partition

Material memory works in mysterious ways. We surround ourselves with things and put parts of ourselves in them. It hides in the folds of clothes, among old records, inside boxes of inherited jewellery, between the yellowing pages of old books, in the crack of furniture and the stitches of frayed, embroidered handkerchiefs. It merges into our surroundings, it seeps into our years, it remains quiet, accumulating the past like layers of dust, and manifests itself in the most unlikely scenarios, generations later.

Material memory works in mysterious ways. We surround ourselves with things and put parts of ourselves in them. It hides in the folds of clothes, among old records, inside boxes of inherited jewellery, between the yellowing pages of old books, in the crack of furniture and the stitches of frayed, embroidered handkerchiefs. It merges into our surroundings, it seeps into our years, it remains quiet, accumulating the past like layers of dust, and manifests itself in the most unlikely scenarios, generations later.

In the case of the Partition, material memory remains an incredibly important, yet seemingly unexplored, way of understanding personal and collective histories, especially through second- and third generation introspections. The notion that where one is from can be understood using what remains of that place opens up a highly sensitive and rich terrain that can help unpack belonging, especially if that place has now been rendered inaccessible by national borders.

***

There are also certain special cases of migratory objects, which must be mentioned here:

First, objects carried across that bind several generations of a family together, as in the case of the women of the Bery family. Its patriarch, Narian Das Bery, had procured from an Englishman in 1933 three stunning pieces of handmade jewellery when the family lived near Shalmi Darvaza in Lahore. These he brought, concealed within their belongings, when they moved across the border to Delhi in 1947. There were two identical peacock bracelets, whose metallic wristbands, flat and mesh-like, were made from pure gold and encrusted with delicate peach pearls barely 3 mm in size. Of these, he gave one to his daughter Amrit and the other to his daughter-in-law Shail. The third piece was a painstakingly detailed brooch in the shape of a fern. This he gave to his wife. On her passing, he presented it to his elder daughter Jiwan, who considered it a part of her mother and safeguarded it though she barely ever wore it. After Amrit’s death, her bracelet eventually passed down to her younger daughter, Rajni, my mother, who too considered it a piece of her mother entrusted to her. She recalled how once, at a dinner party in Delhi, a woman approached her and by simply looking at her hands and the peacock bracelet that adorned her wrist, knowingly declared that she ‘must be Amrit’s daughter’! More than eighty years after Narian Das Bery procured them, these pieces of jewellery bind the three women together, all living in different parts of the world, with the memories of a generation past and a city they yearn to remember.

Second, objects carried across the border years after the Partition by people who made the journey back to their homelands to retrieve items of great value or emotional attachment. Or even objects that were brought across by others—friends, family members or well wishers—for those who migrated, like two name plaques reunited with their respective owners years later. A Rajasthani stone plaque bearing the name ‘Shams Manzil’ in Urdu was installed at the front of a home belonging to an affluent Muslim family in Jalandhar. They were forced to flee to Lyallpur (now Faisalabad) during the riots in 1947. Mian Faiz Rabbani, a boy of sixteen at the time of the Partition, would often reminisce about his past in India, which led him to visit Jalandhar twenty-five years after the Great Divide. Greeted with love and respect by the family who now lived there, he returned to Pakistan a content man. Many years later, when his niece and her husband visited the ancestral house, they saw it was being demolished and the plaque was abandoned. With the permission of the residents of the house, they decided to take the stone slab—heavy with her uncle’s memories—home for him across the Wagah border. In a comparable instance, Justice Bakshi Tek Chand’s family home at No. 6 Fane Road, Lahore, had two similar marble plaques at the front with the words ‘Bakshi Tek Chand’ on one and ‘Shanti Bhawan’ on the other, in English, Hindi and Urdu. Decades after the Partition, the grand house was being demolished and its inhabitants travelled to Delhi, where the justice’s family now lived, and delivered the two plaques to their rightful owners.

Third, objects associated with occupations and professions. Bhabesh Chandra Sanyal, (commonly known as B.C. Sanyal) the famous painter and sculptor born in Assam, disembarked after a four-day journey from Calcutta to Lahore in 1929. Having already seen the Partition of Bengal in 1905 when he was just four years old, he happened to be away from Lahore when the Partition of India took place in 1947. As he struggled to make the journey back to the city where he had set up the Lahore College of Art in 1937 and his studio in the ballroom of Regal Cinema, another artist was taking the same route. Anwar Ali, the cartoonist responsible for the creation of a character called Nanna in the Pakistan Times, found himself on the wrong side of the border in Ludhiana and travelled to Lahore with his family. There he encountered Sanyal and helped him transport several of his important works as he fled the Garden City for good. As the two artists parted, Sanyal presented Ali with a teak easel he had initially brought from home, symbolic of the transference of art from one side of the border to another against the backdrop of communal disharmony. The cartoonist treasured it his whole life and passed it down to his son, the watercolourist, Dr Ajaz Anwar. In another instance, Om Prakash Khanna, sixteen years old at the time of the Partition, recalls his father Malik Tikaya Ram Khanna bringing across the border from Multan to Lucknow a tattered service certificate of his employment at the North Western Railway as trains clerk in Khanewal, both as identification proof and also perhaps hoping it would help him gain similar employment in independent India. Meanwhile, Fayyaz Muhammad Faza, fourteen years old at the time of the Partition, remembers his publisher father determined to carry across from Ludhiana to Lahore all the books he had published, hoping to set up another press once the family had settled down.

Fourth, migratory objects rediscovered decades later through sheer serendipity. Former diplomat Moni Chadha tells the story of how, before the Partition, during wedding celebrations families would borrow items from one another: cutlery, dinnerware, glasses and so on. For easy identification, they would engrave their initials on to the surface of such objects. When his family left Rawalpindi for Delhi in 1947, they left behind a majority of their belongings, including a set of silver glasses engraved with his grandfather’s name: Arjan Singh Chadha. Five decades later, a friend of the family was visiting Canada and accepted the hospitality of a Pakistani family in Toronto. On the dinner table, a generous spread in typical Punjabi fashion included, in an unexpected coincidence, a set of silver glasses engraved with the name Arjan Singh Chadha.

Fifth, objects of sheer utility: things used and needed on an everyday basis. Balraj Bahri remembers his mother frantically packing up all the peetal utensils from their kitchen in Malakwal before they made their way to the refugee camp in district Gujarat. They could not take eatables, so at least if ration was provided at the camp, they would have utensils to cook it in. Similarly, Raj Kapur Suneja now owns the small hand-chakki, a circular stone mortar no bigger than 10 inches in diameter, which her mother-in-law carried from Lyallpur to Delhi, fearful that the family would no longer have access to the freshly ground atta that they had become so accustomed to eating daily.

And, lastly, objects whose stories and memories have been unearthed and preserved by children and grandchildren—second- and third-generation inheritors of the lingering trauma of the Divide. Prof. P.S. Randhawa, a Midnight’s Child, grew up with the knowledge of a dagger that changed the composition of his family forever. Against the backdrop of Partition riots in district Sheikhupura, the first thing he remembers seeing was his mother’s smile and the last he was told his two sisters saw was the desperate blade of their father’s dagger.

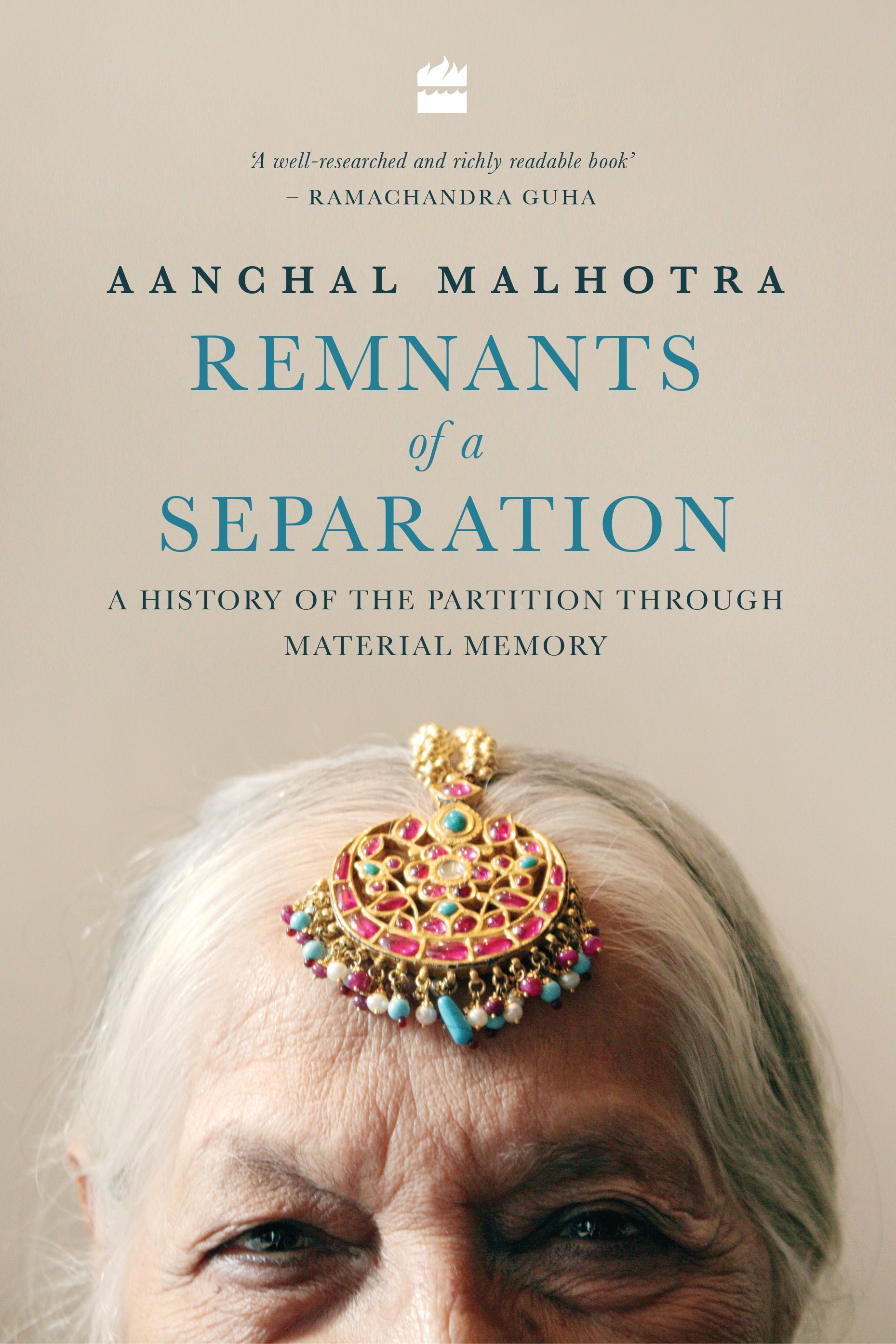

Excerpted with permission from HarperCollins India from Remnants of a Separation: A History of the Partition through Material Memory by Aanchal Malhotra.